Classical Music Review: Boston’s Cantata Singers

Boston’s Cantata Singers opens its 48th season with an eclectic musical mix of the Baroque and the Modern.

By Melanie O’Neill

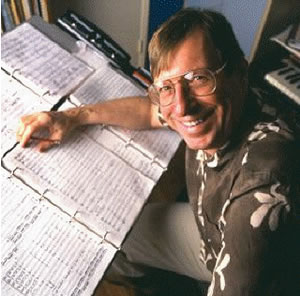

Boston’s Cantata Singers opened their 48th season on November 4th with an interesting mix of sacred and secular music, with two pieces by Johann Sebastian Bach and two by Stephen Hartke. True to the Cantata Singers’ reputation for versatility and musical exploration, the program featured Bach classics as well as the world premiere of Hartke’s vocal work, Precepts.

The program began with Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No. 1 in F. The ensemble brought a bright sound to the festive Allegro, along with a strong rhythmic drive. Without too much exaggerated staccato, the tempo was crisp and lively. The three oboes contributed color and warmth to the movement, countering the alternately stoic and dynamic strings. The fleeting feeling of the Adagio movement provides a sharp contrast. The wavering lines, played alternately by the woodwinds and strings, make use of such devices as neighbor tones and trills, coupled with the broken chords played by the harpsichord. The music leaves the listener with the sensation of wading through water.

Other highlights of the Brandenburg concerto include the Menuetto, which featured a trio as well as a violin solo. The trio, between two oboes and a bassoon, was sleek—the two oboists blended so perfectly in tone that it sounded almost like a duet. Violinist Danielle Maddon showed exceptional virtuosity in her solo passage in the Menuetto. Although it was not the typical Baroque “sound,” Maddon’s almost metallic tone was memorable.

Next came Precepts, featuring not only the Cantata Singers but also the renowned oboist Peggy Pearson. Composer Stephen Hartke composed the piece at the requests of both Pearson and David Hoose, music director and conductor of the Cantata Singers. The composition starts with a rush of action from the orchestra and oboist with Pearson jumping in immediately, showcasing her dexterity and her exquisitely warm tone.

The melancholic second movement, Non Negabis Mercedem Indigentis, contains some of the most distinguishing music of the piece. The Cantata Singers did a tremendous job dynamically transitioning in and out of focus with the soloist. The chorus slipped effortlessly from the dominating sound to a haunting, chant-like state that gave room for Pearson to excel. The final movement of Hartke’s debut piece lacked the character and innovation of the previous two; very little distinguished it from most modern, atonal masses. The awkward jump from Latin to English text without any preparation perplexed rather than challenged the audience.

Hartke’s second program piece was A Brandenburg Autumn, in which he used the instrumentation of Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto to achieve a vastly different end. Harkte’s focus throughout most of the piece was to create mental images rather than distinct melodic lines. In his first movement (Nocturne: Barcarolle) Hartke aims to depict the lakes of Brandenburg. The clashing rhythms that begin the movement suggest contrary movement, such as that of waves beating against a boat. The scene becomes more complex with the addition of more instruments; the breezy lines of the woodwinds suggest wind billowing the sails, while the high pitched, trickling embellishments of the harpsichord evoke rippling water.

Where the first movement succeeded in sonically creating an effective scene, the second movement fails. What was supposed to be reminiscent, according to Hartke, of a “dinner table discussion” generated little incisive dialogue among the elements. The aggressive plucking and spurting from the woodwinds along with the whining brass turned out to be more disjointed than conversational—statements did not answer or echo each other in any meaningful way. There was some beautiful coloring in the eerie third movement, where the interplay between the woodwinds and harpsichord generated a cold and autumnal atmosphere. Rejouissance: Hornpipe, the fourth and final movement, closed the piece on an upbeat note, though it was not as joyful as the title might suggest. Aside from the brass, which was resplendent and solid, the movement was as uneven as the others, once again featuring elusive string parts and dissonant orchestral harmonies.

The plunge back into Bach after an hour-long block of Hartke’s atonal music was somewhat shocking and offsetting. After such dissonance, the Kyrie of Bach’s Lutheran Mass in F radiates an angelic harmony and seamless fluidity. The blending of the voices in the chorus left no pauses between phrasing, giving the music a perpetually flowing line. Hoose, who was much more animated in his conducting of the Mass, cued dynamic contrasts to perfection. The melismas of the Gloria were at times somewhat muffled, but the bright sound of the ensemble made the performance compelling all the same.

The three soloists of the Mass displayed great vocal charisma. Bass James Dargan sang the “Domine Deus,” and the creamy, rich quality of his voice was ideal for this reverent, yet glorifying segment. Soprano Karyl Ryczek displayed refined and expressive vocal abilities in her solo, “Qui Tollis.” Her perfectly consistent vibrato and expressive dynamic intensity made it the most emotional vocal turn of the evening.

The final vocal solo of the Mass, “Quoniam,” was sung by alto Lynn Torgove. Torgove supplied a strong and aggressive presence, showing great vocal agility. The violin obbligato, played by Maddon, created a counter to the solo that both pushed the music forward while adding layers of complexity. The Mass ends triumphantly, with the chorus and orchestra in animated unity before coming to a definitive close on “Amen.”

Melanie

Your review of the Cantata Singers makes me wish that I could have been there to hear the Cantata Singers.

With love and best wishes for all that you do now and in the future.

Ray and I are very proud of you and of your work.