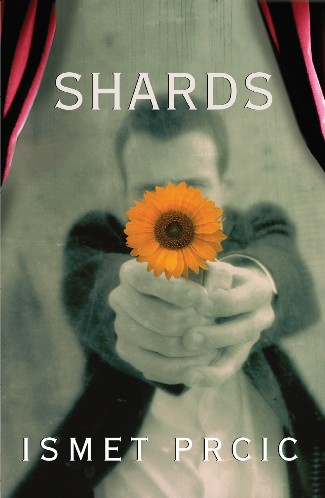

Book Review: Brilliant “Shards”

In this novel, author Ismet Prcic’s confusion is so vivid that it becomes ours, making us participants in the story.

Shards by Ismet Prcic, Black Cat, 392 pages, $14.95.

By Roberta Silman

In his debut novel Shards, Ismet Prcic (pronounced Persick) has written a novel that is as experimental and brutal and heart-wrenching as anything that has come out of any war. His war is the one that broke up Yugoslavia, and Prcic is a Bosnian Muslim born in 1977 in Tuzla trying to make sense of exactly the kind of experience that people who lived through the Second World War vowed would never happen again in Europe in this century.

But it did. Although the title warns us that this will be anything but a linear story, it doesn’t really prepare us for the chaos that is laid out for the reader on almost every page. Throughout the book, we are in the mind of the protagonist Ismet Prcic, who seems to be two people. The first escaped combat and had an adolescence shadowed by war and fell in love and joined a theater troupe that eventually got him first to Scotland and then to California in the late ‘90s where he makes some interesting observations about American life. This is conveyed in ordinary narrative, diaries addressed to his unhappy mother, dreams, and even lectures. Despite an American therapist who urged him “to write everything”— thus the book in our hand — Ismet, known in the States as Izzy, may have committed suicide. Or he may still be alive in the persona of a second character, his alter ego, Mustafa Nalic, who saw combat and was wounded, though not mortally.

It is also possible that there really are two protagonists of this fiction that sometimes seems to be a memoir, but it is a testament to Prcic’s talent that although we read eagerly to see what happens to each one, it doesn’t really matter. For what we have is a world in so many shards that it makes no sense; to try to sort it out seems utterly futile, yet, oddly, not at all exasperating. You just give in to it, as you do when reading someone like Faulkner whom the author has surely read and, in a typically sly aside, refers to towards the end of the book

What makes Shards so compelling is, first of all, the language, Prcic’s second language which he has mastered amazingly well and which has an almost ferocious beauty. Secondly, and as important, is the organization of the book, which gives it a sense of urgency even though there are many repetitions—scenes seen from different points of view, time scrambled then unscrambled, changes of narrator from first to third person and even sometimes second person when you almost feel as if the author is trying to decide how he really feels about something. This only makes the novel more appealing because Ismet’s confusion is so vivid that it becomes ours, making us participants in this story. Here he is, feeling utterly separated from himself, observing himself as if in a dream:

When I looked, I saw myself from the back, walking away, carrying on. I stood there . . . It sure looked like me. It sure looked like I knew what I was getting into.

Then I was moving again, my sneakers swallowing meters of gray sidewalk, but something was off. Something was missing. I slowed down and turned around, and there I saw myself standing in front of the bank, unable to move, unable to catch up to me, as though there was an invisible barrier separating two possible futures that only a certain percentage of me could pass through. I wanted to stop and go back, but my own feet kept moving.

And here he is after he reacts inappropriately to what are merely fireworks:

No, I had never before that day seen fireworks. Neither had Ramona, nor Omar, nor Boro. Asmir and the musicians were older. They remembered with fully formed bodies and minds life before the war. Before chaos, they’d known order, before senselessness, sense. They were really out of Bosnia because leaving chaos to them felt like returning to normalcy. But if you were forged in the chaos, then there was no return. There was no escape. To you chaos was normalcy. And normalcy was proving to be an unnatural, brittle state.

Just when you think you can’t take any more, Prcic gives you yet more detail, the book expands as more notebooks are added, and the end, his mother’s letter to her son, is excruciatingly sad. It was then that I turned back to the epigraph to the second notebook from Samuel Beckett: . . . a story is not compulsory, just a life, that’s the mistake I made, one of the mistakes, to have wanted a story for myself, whereas life alone is enough.

To have had such a life when you are so young is hard to convey without becoming sentimental or pathetic, yet Ismet Prcic has done it brilliantly. In an interview with BOMB magazine he says:

War is the greatest teacher of them all. War shatters everything you think you know and believe and shows you that society, reality, things you hold dear are simply illusions . . . Conventional storytelling just cannot seem to capture the shattering of a psyche that occurs when humans experience war. How can a shattered psyche write an orderly story? We owe it to the dead to keep trying to capture that experience though.

Other critics have insisted on comparing him to his older compatriot, Aleksandar Hemon, who is also a terrific writer (his most recent piece was a New Yorker essay about losing his second daughter to a brain tumor, another kind of hell, not unlike war). But wonderful writers should not be grouped according to nationality, and each has his own unique voice. In our own country, we have Kurt Vonnegut and Tim O’Brien and Michael Herr and many others, all distinct voices who have explored similar subjects.

Which brings up the question: Another book about war? Isn’t it enough to read the papers and listen to the news? But Prcic is doing something more comprehensive. He explains, in a PW interview:

People think that once you get out of the war zone, everything will be fine. A lot of immigrant fiction is about successful immigrants. You survive hardships, endure, and all is wonderful. But there are all these people who want to go back or who just shrivel and die in a corner of Iowa or New York or wherever. Nobody hears those stories.

Yet here is the very place to start.

Roberta Silman is the author of Blood Relations, a story collection; three novels, Boundaries, The Dream Dredger, and Beginning the World Again, and a children’s book, Somebody Else’s Child. She can be reached at rsilman@verizon.net

Terrific review, Roberta–both your writing, and his! This book goes on my list.