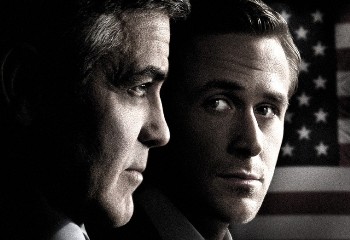

Movie Review: “The Ides of March” — Even with George Clooney, It’s Politics as Usual

The Ides of March tells the same old political story: we know how tedious the campaign season is, we know that deals are made behind doors and that all that really matter are the numbers.

The Ides of March. Directed by George Clooney. At screens throughout New England.

By Maraithe Thomas

It’s barely mid-October and already Americans have been inundated with at least several Republican debates between candidates vying for a spot on the November presidential ballot. That’s November 2012. To be true, we’ve been hearing about next year’s election since the last one. So if you tire a bit, if you want a little George Clooney and Ryan Gosling infused into your political diet, a little Hollywood romanticizing of the whole charade, certainly turn to The Ides of March. Clooney’s fourth directorial effort will entertain you, but it won’t shock you as it’s perhaps intended to—we’re used to the game by now.

The film centers on the campaign of Democratic candidate Mike Morris (Clooney) on the eve of the Ohio Presidential Primary. Morris’s campaign, helmed by the staunch Paul Zara (Philip Seymour Hoffman) and, second to him, young hotshot Stephen Meyers (Gosling), is a cutthroat environment, a hectic one, where every decision and number seems terribly consequential. (“The polls. What are the polls saying?”)

It’s made clear early on that Morris is the best candidate. Besides the fact that we barely see his opponent, it surfaces that the Republicans may want to intentionally sideswipe him so as not to have to face him in the election. The film tries to lend an Obama aura to Morris—there’s a Shephard Fairey-style poster of Clooney in the office—but he lacks the charisma Obama had when he was campaigning.

But even though Morris should win—he’s honest, likeable, albeit a bit dull—it becomes clear that winning the nomination hinges on the endorsement of a North Carolina senator, who seems to be fine with siding with whoever offers him the best cabinet position. This goes sharply against Morris’s political values, but is it worth compromising to win? Again, though many of us would like to believe this doesn’t happen just because it shouldn’t, many of us also know that this happens American politics, for better or worse, and it isn’t all that thrilling on screen.

The film opens in darkness before lights come up on Gosling—a face anyone who saw Drive should be excited to see so soon again—on a stage set for a debate. Exuding confidence and wit, he does a mic check for Morris, delivering verbatim what we’ll see Clooney reiterate during the real thing. We’re drawn to Gosling; we’re not drawn so much to Clooney. He’s kind of just there. Parts of the movie that show his political speeches verge on boring, in the same way that speeches made by real politicians are boring, but here, we don’t have a stake in paying attention, i.e. Clooney is not going to be our next president. (Probably).

Gosling’s character, less hardened in the campaign regimen than Zara, seems untouchable. He’s confident his candidate will win; he deals/flirts with New York Times journalists and even scores a date with campaign intern Molly Stearns (Evan Rachel Wood). But a series of events involving Molly and a fateful meeting with Republican campaign head Tom Duffy (Paul Giamatti) sends his perfect world spiraling.

And that’s where the fierce politics of politics really come to a head. Gosling’s character proves to be overly idealistic, and it burns him—badly at first, but in order to recover, he has to make some painfully ruthless decisions. Nobody can stick by their values completely if they want to succeed. Indeed, success seems to be measured by how well you can morph into something other than yourself.

But because today’s real-life politicians gab so much in interviews, documentaries tell all, and politics are reported exhaustively in the press, none of these revelations about the unforgiving, deal-making nature of a presidential campaign are all that shocking. We know how tedious the campaign season is, we know that deals are made behind doors and that all that really matter are the numbers. But if you’re not as jaded in the ways of the political season—if you’re more a Gosling character than a Hoffman—this movie will deliver on its promise to disturb.