Visual Arts Feature: Artists John Heliker and Robert LaHotan — Spirits of Generosity

Robert LaHotan was a fine abstractionist before he fully turned his energies to landscapes and interiors in his mature works. This exhibition, which spans 25 years, shows him alternating between abstract and figurative styles with many paintings landing somewhere between the two.

Robert LaHotan: The Early Years. At Yvette Torres Fine Art, 21 Winter Street, Rockland, Maine.

By Franklin Einspruch

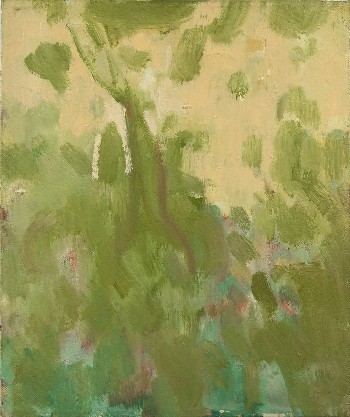

Robert LaHotan, ROCKS AND TREES AT NIGHT, 1962, oil on linen, 8 x 10 inches. Photo: Yvette Torres Fine Art.

John Heliker and Robert LaHotan, known as Jack and Bob, were painters from New York who bought a property on Great Cranberry Isle, ME that had once been a shipbuilding operation. They met as teacher and student, then became a couple and remained one throughout the rest of their lives, pursuing art and teaching careers in New York and painting and living the good life in Maine. “Theirs was a true marriage,” says Patricia Bailey, director of the Heliker-LaHotan Foundation, which operates out of what was once Jack’s and Bob’s home and studios and where I am currently an artist in residence.

I was given a quick but touching overview of LaHotan’s life thanks to a talk delivered by Bailey at Robert LaHotan: The Early Years at Yvette Torres Fine Art in Rockland, ME. Also on hand was Isabelle Storey (formerly Evans), who read from her book Walker’s Way: My Life with Walker Evans. Evans befriended Jack and Bob and recorded his visits to Big Cranberry, as they call it here, in photographs. See, for instance, Jack Heliker’s Bedroom Wall, Cranberry Island, Maine in the collection of The Museum of Modern Art. There is also a famous Evans depicting an old stove. That stove is downstairs from where I’m typing this.

Bob and Jack treated visiting friends to dinners that featured excellent conversation, many cigarettes, and Bob’s renowned cooking. Jack was permitted at most to make salad dressing, but his company must have been fascinating. I have perused his library, which contains volumes covering Eastern and Western religious thought, marriage and homosexuality, ancient and modern philosophy, and a great variety of biographies.

Robert LaHotan, WORKSHOP STILL LIFE, 1968, oil on linen, 46 x 40 inches. Photo: Yvette Torres Fine Art.

I had planned to review the LaHotan show for this publication, but it is now out of the question. Because everyone calls him Bob, I do as well. Communal dinners here begin with a toast to Jack and Bob. I am painting in Bob’s studio, looking eastward over the bay. I have seen an orange moonrise reflected in the waters. I have watched the tides come and go and have twice painted the shoreline. Between the studio and the house, a stone and a circle of wildflowers marks the place where Bob’s ashes are interred. Bob loved wildflowers, I’m told. I make a point of walking by once a day to thank him for his studio, for cultivating the buildings and landscape into a perfect painter’s retreat, and for dedicating it after his death to the work of future artists.

The stone that marks Jack’s ashes is also on the property, not far from Bob’s studio. A few heads of garlic sprout among Jack’s wildflowers. Jack loved garlic, I’m told. Jack was 18 years older than Bob, but Bob only survived two years after Jack passed away in 2000. Theirs was a true marriage.

I am of no mind to criticize Bob’s art. I’ll say instead that he was a fine abstractionist before he fully turned his energies to landscapes and interiors in his mature works. This exhibition, which spans 25 years, shows him alternating between abstract and figurative styles with many paintings landing somewhere between the two. Even in the fully abstract pieces, it’s easy to see landscapes or interiors trying to force their way into the foreground. I get the sense from them, despite their merits, that Bob was working somewhat against his natural tendencies in an effort to deal with the dominant painting style of the era. There are artists who are abstractionists to the core. Bob wasn’t one of them. But neither was, say, Richard Diebenkorn or Philip Guston. It’s not necessarily a liability.

It can even be a boon. One way of making an abstraction is to abstract it from something. In Bob’s case, it was a patch of forest floor such as Green and Peach Woods Study (1960) or the dim light of an old shed such as Workshop Still Life (1968), in which one can still detect the wooden construction and cluttered interior, however transformed.

Robert LaHotan, GREEN AND PEACH WOODS STUDY, 1960, oil on linen, 12 x 10 inches. Photo: Yvette Torres Fine Art.

For paintings in which objects are barely recognizable, they convey a powerful sense of place. Potted Plant by a Window (1960) captures the comforting decor and extensive gardening, both indoors and out, that have been lavished upon the house where I have been living for two weeks. Rocks and Trees at Night (1962), at only 10 inches wide, nevertheless renders the broad, foreboding forms that you see when the light is disappearing and you are becoming the most vulnerable thing in the New England woods.

In painting here, especially in the very studio where these works were created, I am following a formidable act. But a spirit of generosity lingers over the place, and it comes to my assistance. Over the last few weeks, I’ve learned of the extensive network of artists who count Heliker or LaHotan as a beloved teacher. In honing a property to serve the many needs of painting, companionship, domesticity, and reflection, then dedicating it to further art-making, they have left a rich teaching that lives after them. Maine features much natural beauty, but the setting is additionally inspiring because they made it that way. As we say at dinner, here’s to Jack and Bob.