Book Review: “The Word Exchange” — A Generous Gift

For everyone who feels the attraction but lacks the study, The Word Exchange is a huge gift. It’s the most generous sampling I’ve seen of poetry translated from Old English and collected in one volume.

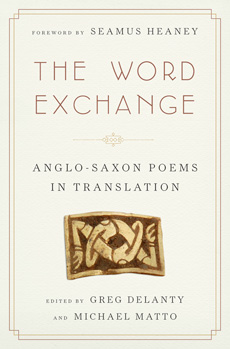

The Word Exchange: Anglo-Saxon Poems in Translation. Edited by Greg Delanty and Michael Matto. Norton, 557 pgs., $35.

By Maryann Corbett

In 2009, when an enormous hoard of Anglo-Saxon gold was found in Staffordshire, the news coverage and wide public interest reminded me how strongly readers are drawn to that period of history. A decade earlier, the best-seller status of Seamus Heaney’s translation of Beowulf spoke to the same attraction. Early England’s history, culture, and literature compel us somehow: somber beauties just out of reach, tantalizingly conveyed in a language that seems to be ours but can’t be grasped without special study.

For everyone who feels the attraction but lacks the study, The Word Exchange is a huge gift. It’s the most generous sampling I’ve seen of poetry translated from Old English and collected in one volume. (Linguists like the term “Old English” for the language because it’s part of the consistent naming system that progresses through Middle English to Modern English. But historians like “Anglo-Saxon” for the period, and the rest of the world seems to prefer that term’s romantic ring.) It’s certainly the largest one-volume collection I know of poetic translations of these works, since the Everyman volume edited by S. A. J. Bradley, although very inclusive, contains only prose translations. It has something for everyone, and we can slice and dice “everyone” in a number of ways.

The book will undoubtedly appeal to the same general readers who read about the Staffordshire hoard and bought the best-selling Heaney. But it will also appeal to everyone interested in translation per se and to everyone interested in seeing how many different poetic techniques can be applied to these poems. The techniques are very different, and the translators’ approaches are very various.

Variety might feel unexpected, since Old English poetry has a certain uniformity: all of it is written in four-stress, alliterative lines. The pattern of alliteration can vary—but not much. The number of syllables in a line can vary; the number of stresses cannot. A good many of the translating poets have maintained the general shape of the four-stress line. Derek Mahon keeps the rules of stress and alliteration strictly—

Known throughout Britain, this noble city.

Its steep slopes and stone buildings

are thought a wonder; weirs contain

its fast river. . . .

—and Robert B. Shaw, Dennis O’Driscoll, David Slavitt, and others keep them approximately. But just as many have followed their own roads. Some of those roads are formal and metrical: Mary Jo Salter uses three stresses per half-line; Rachel Hadas uses some end-rhyme to echo the end-repetitions of the maxims; and A. E. Stallings deploys the whole sonic artillery—tight meter in bouncy dactyls, along with alliteration, assonance, and both internal and end rhyme—for the unusual work commonly known as “the Anglo-Saxon Riming Poem”:

The Lord lavished life on me I had it all:

Blessings were rife for me honor in hall,

Clad in the gladsome cloth of the looms

dyed with the handsome hues of the blooms….

Other treatments are in open form, demonstrating all kinds of different decisions about where to break lines. The maxims seem to invite the plainest treatments, the charms the wildest ones. While the Wall Street Journal’s reviewer has tut-tutted a bit over poets’ failure to stick to the original rules, I think the book is all the better, and more attractive, for its metrical and technical variety.

Degrees of faithfulness in the translating vary too. This is not a flaw; it’s inevitable. All the translations are by contemporary poets—you won’t find Pound’s “Seafarer” here—and their ways of getting at the essence of a poem are as different as their ways of making poems generally. For example, Yosef Komunyakaa’s “The Ruin” untangles the language and gives us a muted paraphrase that goes with the deep sadness of the contents:

Look at the elaborate crests chiseled into this stone wall

shattered by fate, the crumbled city squares,

and the hue and cry of giants rotted away….

Other poets let the strangeness, particularly of the riddles’ language, be as strange as it is, as here in Molly Peacock’s “Riddle 29”:

I watched in wonder, a bright marauder

bearing its booty between its horns.

An etched ship of air, a silver sky-sliver,

it lugged a month’s loot from its raid on time

to build a great bower from all it brought back….

In a fascinating appendix, 12 of the translators supply detailed notes that discuss these variations. They talk about translation as a practice of interpretation akin to close reading. They talk about meanings that tip back and forth between the pagan and the Christian in the culture of the poems. They talk about their differing decisions to veer away from literal meaning or hew closely to it. This book might be unique in facing those differences so squarely.

Another of the book’s great strengths is that it includes the originals on facing pages—translation on the right where it will be looked at straight on, original on the left, available to be glanced at, not in first focus but available to tempt to reader to try to match word with word and to learn. The facing-page treatment also shows us how dense the diction of original poems is, a phenomenon probably noted by everyone who grapples with them. David Ferry’s excerpt from “Genesis A” and Marcia Karp’s translation of “Riddle 42” show how much modern English line can be played out from the spool of the original if one tries to spin all the possible elements of the meaning.

The large-scale organization of the book is worlds more attractive than the presentation the student might find in an introductory, Old English grammar and literature survey. The readings, since they don’t need to be tied to the gradual building-up of grammar and vocabulary, can be organized in ways that appeal to different curiosities. The book doesn’t dump the entire load of riddle-lore out at once, as one would do if one were concentrating on a particular Old English manuscript, like the Exeter Book. Instead, it spreads it out in seven (magical number!) riddle-hoards, interspersed with groupings of poems that fit a given theme.

The first group—craftily chosen, I think—is the “Poems of Exile and Longing.” Those might well be the Old English poems best remembered by people who studied English literature long ago: “The Seafarer,” “The Wanderer,” “Deor,” and others like them, those sad songs of lordless thanes, the poems that made me feel, in my student days, that in Old English it is somehow always winter:

As soon as the sober man wakes

he sees nothing but fallow furrows;

seabirds paddle and preen feathers;

snow and frost combine forces.

Then his heart weights heavier, sore

for the loved lord, sorrow renewed . . .

The ache of “The Wanderer” comes through in Greg Delanty’s translation both for those who know the poem already and those who meet it here for the first time.

The second thematic group is another well-remembered one: the poems about historical battles like Maldon and Brunanburh. But another great strength of the book is that it goes beyond the well-remembered and includes groupings of “poems about living,” “poems about dying,” biblical stories and saints’ lives, other religious pieces, and magico-religious remedies and charms. For the people who persist in thinking that Anglo-Saxon poetry is all battles and dragons, this book is a fine corrective.

The editors have provided introductions to the history, the poetic form, and the original sounds. They’ve supplied appendixes that give the solutions to the riddles and that correlate the poems with their scholarly text base, The Anglo-Saxon Poetic Records. There’s a bibliography for further reading. There’s an index of titles, translators, and first lines. There’s a useful accompanying website. All the serious elements are here that would serve for a course on this literature in translation. The only lack I can think of is a note explaining that more than one system exists for numbering the riddles.

Nothing about the heavy stuff is off-putting, though, and the delights are brought to the fore. A reader can dip into the book anywhere and take pleasure. But the great thing about the collection is that the varieties are all in conversation with one another—in discourse and dealing and exchange. The book’s apt title recognizes those conversations, as well as giving a tip of the hat to an Old English phrase from the poems: wordum wrixlan, “to exchange words.” It’s a phrase that refers both to the making of poems and to the sharing of thoughts, the opening of the heart.

Tagged: Anglo-Saxon Poems, Greg Delanty, Michael Matto, The Word Exchange

I haven’t read OE and ME since college, and look forward to taking a look at this collection. It’s good to know about the Website, too.