Book Commentary: Three Weeks Before the Mast — Reading “Moby Dick”

By Gerald Peary

A slow thinker, I read 600 pages into Moby Dick before putting my finger on the book’s key tension. It’s between Ishmael’s intense and ecological whale love and the central story, which chronicles the wanton murdering of whales, man’s unconcern with destroying the natural world.

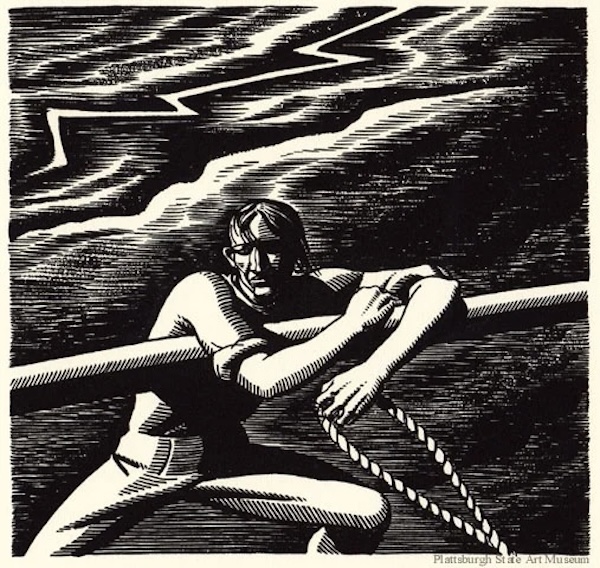

This August 2025 was my designated Herman Melville month. I chose to read Moby Dick in an early Modern Library edition, made instantly wondrous by the accompanying Rockwell Kent illustrations. (There are many of them, reprinted from a 1930 Random House version.)

This August 2025 was my designated Herman Melville month. I chose to read Moby Dick in an early Modern Library edition, made instantly wondrous by the accompanying Rockwell Kent illustrations. (There are many of them, reprinted from a 1930 Random House version.)

I hadn’t tackled Moby Dick since high school and this volume weighed in at 822 pages. Would I actually get through it in the next few weeks? I once quit on The Brothers Karamazov in the middle. Some years ago I purchased the preferred Edith Grossman translation of Don Quixote. It eyes me from my bookshelf.

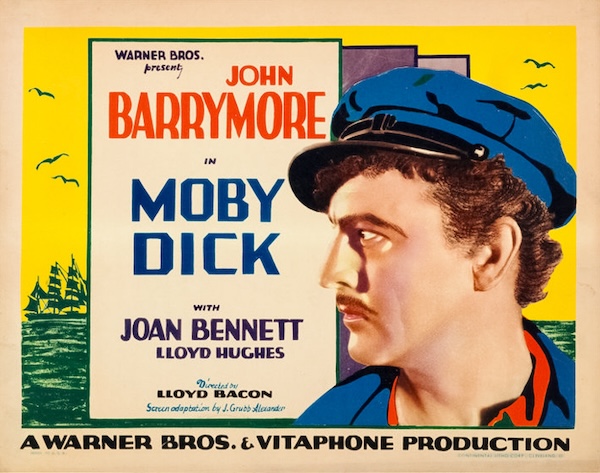

1) The last Melville that I read was the thorny and difficult The Confidence-Man. I expected Moby Dick to be equally intimidating. Instead, the early pages, an on-land prelude before Ishmael sails away on the Pequod, are easily comprehensible and sometimes light and funny. Ishmael is a congenial narrator! A serious high point is Father Mapple’s sermon from the pulpit in New Bedford telling of Jonah and the whale and of Jonah’s sinning and repentance and deliverance by God from the sea. Something we need to remember as the book rolls along? I recall this sermon also being a highlight of director John Huston’s 1956 Moby Dick movie, a scene filmed on location in New Bedford and with Orson Welles formidable as the mighty preacher.

At page 36 I’ve come to an episode much discussed by contemporary readers of Moby Dick: What’s going on at night with Ishmael and Queequeg? “I found Queequeg’s arm thrown over me in the most loving and affectionate manner. You had almost thought I had been his wife… Thus, then, in our heart’s honeymoon, lay I and Queequeg — a cozy, loving pair.” In 1960, critic Leslie Fiedler shook up the literary world in Love and Death in the American Novel with his inflammatory essay “Come Back to the Raft Ag’in, Huck Honey.” Therein, he declared an “innocent homosexuality” in the interracial twosomes of Moby Dick’s Ishmael and Queequeg, and Huck and Jim in Huckleberry Finn. A blasphemous allegation then for straight-thinking readers of these two revered books! Even if “innocent” meant “no sex.”

In 2025? Who gets anxious about what’s going on under the covers with Melville’s two shipmates? I found their shared-bed friendship sweet and touching.

2) I was nicely surprised to find that Melville writes with relish about food. Here’s a fine recipe for a New England clam chowder: “It was made of small juicy clams, scarcely bigger than hazelnuts, mixed with pounded sea biscuit, and salted pork cut up into little flakes; the whole enriched with butter, and plentifully seasoned with pepper and salt.”

The setting has switched on page 91 from New Bedford to Nantucket, where Ishmael and his new friend Queequeg check out and then sign onto the Pequod for a three-year whaling voyage. Ahab, captain of the Pequod, has yet to appear in the flesh. He is described to Ishmael: “I know, too, that ever since he lost his leg last voyage by that accursed whale, he’s been kind of moody…” KIND OF MOODY? Let’s find out more as I read on.

3) I’m 240 pages in and Moby Dick continues to be a page-turning pleasure. Credit Melville with slowly building suspense. We the reader and our storyteller Ishmael have both heard much by now about this Captain Ahab; but he doesn’t arrive on deck of the Pequod until page 176, when the ship is far off at sea. Ishmael describes his ghoulish presence: “He looked like a man cut away from the stake, when the fire has overrunning wasted all the limbs without consuming them.” It’s not until page 233 that Ahab summons his crew on deck and nails gold-pieces to the mast that will be offered to whomever “raises me that white-headed whale.” A white whale? Ishmael has told the reader that all sperm whales are black. Also on page 233: “Captain Ahab,” said Tashtego, “that white whale must be the same that some call Moby Dick.” Ah, so that finally explains the book’s title: “Moby Dick, or a Whale.”

A decided nonscientist, I had been approaching with trepidation Melville’s infamous inter-chapters of scientific data about whales. Many have put Moby Dick down at this point, stifled by their dryness, or guiltily skipping past these interludes to get back to the narrative. I admit, pages 190-207 were trying, where Ishmael stops his story cold and tells the reader: “It is some systematized exhibition of the whale in his broad general that I would now put before you.” But slowly I realized that the fiction continues. The taxonomy offered is not a long encyclopedia entry. It’s the story of whales as voiced by a nerdy amateur fan, Ishmael; and in places his version of science is wobbly, speculative, or even dead wrong. Fake news! For example: “I take the good old-fashioned ground that the whale is a fish … a whale is a spouting fish with a horizontal tale.” Wrong! Google: “No, whales are not fish. Whales are mammals.” We’ll never know if Melville also believed that a whale is a fish, or that he did know and that dear Ishmael here is established as an Unreliable Narrator.

4) It would be difficult to find them in the phone book. All the officers in Moby Dick have only last names starting with Ahab and Starbuck, and all the crew have only first names beginning with Ishmael and Queequeg. The first 240 pages of the novel are straightforward first-person narration by Ishmael. Pages 240-56 are Melville’s first experiment in point-of-view, a sudden shift to a play-within-the-novel with stage directions in italics and in brackets: “[Ahab sitting alone and gazing out].” Dare I say that this section is not totally successful — three imitative Shakespeare-style soliloquies by Ahab, Starbuck, and Stubb, followed by a very flat choral section of harpooners and sailors — like clunky Eugene O’Neill?

All is forgiven because we soon come to perhaps Melville’s most dazzling chapter, pages 272-83, “The Whiteness of the Whale.” Here is where Ishmael makes a telling case that though whiteness is usually considered as benign, “significant of gladness,” yet “there lurks an elusive something in the innermost idea of this hue, which strikes … a panic in the soul.” When on “a midnight sea of milky whiteness,” a sailor like Ishmael feels “a silent supernatural dread; the shrouded phantom of the whitened waters is horrible to him as a real ghost.” That’s a long way to say that Ishmael seems aligned with Ahab’s acute paranoia about Moby Dick, a belief that this white whale being chased by the Pequod is hellish, diabolical, otherworldly.

All is forgiven because we soon come to perhaps Melville’s most dazzling chapter, pages 272-83, “The Whiteness of the Whale.” Here is where Ishmael makes a telling case that though whiteness is usually considered as benign, “significant of gladness,” yet “there lurks an elusive something in the innermost idea of this hue, which strikes … a panic in the soul.” When on “a midnight sea of milky whiteness,” a sailor like Ishmael feels “a silent supernatural dread; the shrouded phantom of the whitened waters is horrible to him as a real ghost.” That’s a long way to say that Ishmael seems aligned with Ahab’s acute paranoia about Moby Dick, a belief that this white whale being chased by the Pequod is hellish, diabolical, otherworldly.

5) I’m sure everyone sitting with Moby Dick jumps up when Ishmael says this about whiteness: “… this pre-eminence in it applies to the human race itself, giving the white man ideal mastership over every musky tribe.” What racism, what a hearty defense of colonialism! And if Ishmael says it, does it mean that Melville also feels this way? If you are very PC, do you shut the book at this point, page 273, and refuse to read further? And what about slavery? When Ishmael describes passing slave ships it’s not to condemn them but only to note that those slaves who die on the voyage are dumped overboard, fed to the sharks. Somewhat later in the book there is a Black cook who is chastised for overcooking a whale steak and he’s given to speak awkward Black dialect like railroad porters in 1930s Hollywood movies. And there’s Pip, the Black boy Pip. What do we make of all this?

Literary historians say that Melville opposed slavery, though he wasn’t a Thoreau-like activist or abolitionist. In Melville’s defense, can’t we say that Ishmael and Queequeg, a person of color, are genuine friends? Equals? If anything, Queequeg’s status on the Pequod is higher because he is a valuable harpooner. He has a higher salary. My semi-woke answer: acknowledge the pockets of racism in Moby Dick, but keep on reading this incredible book. Here is what AI in its 2025 wisdom says about all this: “There is no simple answer to whether Melville was racist. His works contain both elements that can be interpreted as racist and elements that critique racism. His writing reflects the complexities and contradictions of race relations in 19th-century America.”

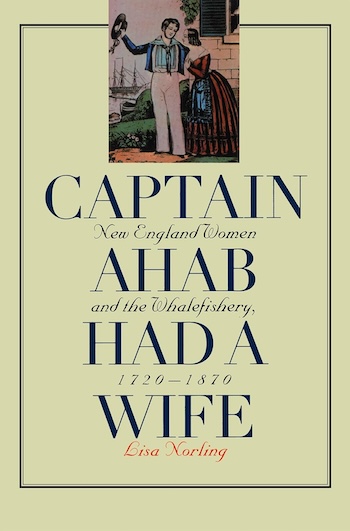

6) Did you know that Ahab was married, with child? I didn’t, and was educated to that in one undramatic sentence early in the novel about Ahab’s life in Nantucket. I’m 350 pages into the book and it’s never been mentioned again. Why did Melville include this back-story detail? Presumably it will come back later on. My wife Amy calls Ahab a typical male high modernist, obsessed with his quest and indifferent to his domestic life. I call him a deadbeat dad. He’s not sending money home to his wife and kid. Switching topics: Ahab is so akin to many Poe protagonists — gloomy, morbid, antisocial, blood-crazy — I wondered if Melville had read Poe. I found at least one scholar, Jack Scherting, who, in a 1968 essay, found Moby Dick connections, perhaps coincidental, with the oceanic quest in The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym (1838) and with the demented sea captain of MS. Found in a Bottle (1833), the latter also an apocalyptic tale of a watery death. This scholar noted that in 1861, though long after the publication of Moby Dick, Melville gave his wife a present of The Works of the Late Edgar Allan Poe. So we do know that Melville admired Poe. Was Poe an influence on shaping Ahab? Maybe. On the other hand, Melville had his pick of melancholic estranged males in the tales of his pal Nathanael Hawthorne, to whom Moby Dick is dedicated.

7) The deeper you read into Moby Dick, the more of the book becomes those chapters in which Ishmael lectures you, mansplaining about whales. Probably more about whales than you would ever wish to know. My strategy is to take a deep breath and try to enjoy them. And do you know what? They mostly are enjoyable, about whales’ eyes on the side of their heads, their lack of noses, their inner ears, their small brains but active spines. And whale stories in mythology, like Hercules being swallowed by one Jonah-style, also Ishmael’s claim that what St. George famously slew was not a dragon at all but a whale! Ishmael is whale-crazy. And unlike the bloodthirsty Pequod crew, he is ambivalent about killing one. Pages 510-22 tell of the chasing down and too-easy murder of “… a huge, humped old bull, which … seemed afflicted with jaundice or other infirmities.” Ishmael mourns this noble old whale’s impending death: “… he had no voice, save that choking respiration through his spiracle, and this made the sight of him unspeakably pitiable.”

It’s not only Ishmael’s whale-biology speechifying that interrupts the sailing-of-the-Pequod saga. Pages 352-78 of my Moby Dick are an uncomfortably fit novella-length chapter, “The Town-Ho’s Story,” told Conradian style with Ishmael narrating to “a lounging circle of my Spanish friends” a tale told to him. It’s a shaggy-whale story about another sailing vessel and eventually about the fatal battle of this ship’s chief mate, Radney, with Moby Dick himself. This chapter is most interesting as a prefigurement of Melville’s last work, Billy Budd (1891). Radney, like Billy Budd‘s Claggart, is jealous of the popularity and good character of one of the shipmates, Steelkit, and has Steelkit chained and imprisoned. Steelkit eventually triumphs, though not poor foretopman Budd.

8) A slow thinker, I have read 600 pages into Moby Dick before putting my finger on the book’s key tension. I have felt it but couldn’t name it. It’s between Ishmael’s intense and ecological whale love, expressed a hundred ways in those inter-chapters, and the central story, which chronicles the wanton murdering of whales, man’s unconcern with destroying the natural world. Each killing of a whale in the book agonizes Ishmael more. I feel certain that Melville means these killings to upset his readers. Of course, Ishmael makes no complaint to his bosses on the Pequod. He is a familiar American figure, the Reluctant Warrior, obeying orders, fighting on for causes in which he doesn’t believe, whether it’s Little Big Horn or Vietnam. Or carrying out the evils of Donald Trump.

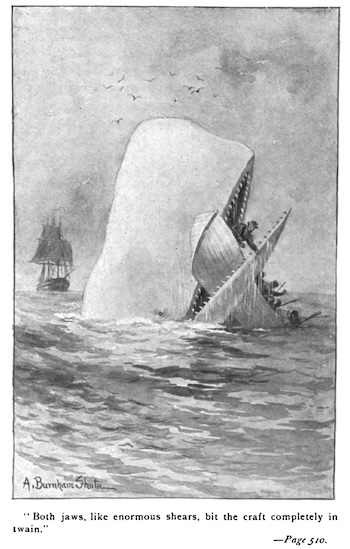

Illustration from an early edition of Moby-Dick, 1892. Photo: Wikimedia

“Oh, he’s a wonderful man!” declares Stubbs about Ahab. “‘Terrible old man!’ thinks Starbuck, with a shudder.” But so far, Starbuck says nothing negative about his captain aloud. And Ishmael? Don’t look to his narrative for overt criticism. He stoically does his sailor duties, like all else aboard the Pequod.

Ahab gets a deserved bad rap for his suicidal obsession with trekking after Moby Dick, imperiling his crew. But let it be noted that day to day he’s not a bad captain, like, say, Bligh of the HMS Bounty — just a very passive one. When his crew captures an occasional sperm whale, they do so without his leadership or instruction. His men are fed, there’s no corporal punishment, no whipping, no walking the plank. Mostly, Ahab just broods and stays out of the way. And occasionally walks the deck and partakes of a soliloquy. When the Pequod meets up with other ships, Ahab has only one question: Have you seen a white whale? When they haven’t, he sighs and slinks off. On a daily basis, he has little contact with the men on his ship except for his unlucky officers, who must share with him each evening a silent melancholy dinner.

9) A learned friend of mine declared, “Moby Dick cannot be the greatest American novel because it has no women in it.” So Red Badge of Courage is also eliminated; and are women in Huckleberry Finn enough in the story to qualify Twain’s masterpiece for “the greatest”? Maybe Tom Sawyer is better situated because of the central presence of Becky Thatcher and Aunt Polly? I digress. What’s striking in Moby Dick is not the lack of female presence but that nobody aboard the Pequod cares about it. No seaman pines for the girl back home, no randy sailor lobbies for shore leave and a bordello visitation. Is this the normal puritanism and reticence of a 19th-century novel? Or is this peculiarly Melville? I’ll say it: Might this absence be a repressing of the kind of sailor love Melville secretly desired? And will bubble up in the later Billy Budd. What do you say, dear Freudian readers?

10) I’ve discussed Ishmael’s ambivalence about whale killing as a central theme of Moby Dick. Ecological-minded current readers may be disappointed when they reach what is page 659 in my book. Here Ishmael argues that sperm whales like those being hunted down by the Pequod are not in danger of becoming extinct. Whale boats on the sea for four years might “carry home the oil of forty fish.” Ishmael contrasts that to hunters and trappers in the West who, in the same amount of months, “would have slain not forty, but forty thousand and more buffaloes.” From our modern vantage, has Ishmael proven right? Says the gospel of Google: “The sperm whale is listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act. The sperm whale is protected throughout its range under the Marine Mammal Protection Act.” (Please don’t inform Trump.)

11) Hemingway was 27 when The Sun Also Rises was published, Fitzgerald 28 with The Great Gatsby. Still, Melville seems incredibly young to have published Moby Dick at 31. He would live in literary obscurity for 40 years after. In 1850 Melville wrote courageously, “it is my earnest desire to write the sort of books which are said to ‘fail.’” He succeeded too well with the 1851 failure of Moby Dick.

Everyone agrees that Moby Dick is sometimes self-consciously Shakespearean, most clearly Ahab’s Elizabethan soliloquys, and the typhoon that Ahab suffers surely echoes the storm in King Lear. But in the 700 pages I’ve now read, I can’t recall one direct reference to the Bard. Rabelais, yes, and twice Ishmael has talked of Dr. Johnson. But no Macbeth, Hamlet, Prospero, whomever. And there’s no Falstaff equivalent among the Pequod crew.

12) Does Melville have a sense of humor? Hawthorne described his friend’s “characteristic gravity and reserve of manner.” He’s no riotous Mark Twain, but there are consciously funny moments in Moby Dick beginning with the farcical first meetings of Ishmael and Queequeg. At least once, Ishmael turns punster, joking that a one-legged character (not Ahab) never made a “stump speech.” Also Ishmael makes jest of British law by which the royal family has the right to claim any whale caught by an Englishman: the king gets the head, the queen the tail! I was amused by a scene in which those from the Pequod go aboard a French ship and, playing about, brazenly call the captain “a monkey” to his face because the Frenchman understands no English. Finally, I will note a screwball episode in which Ahab boards another ship because that captain has lost an arm to Moby Dick. Instead of meeting his match, someone as revengeful and monomaniacal as himself, Ahab encounters a pragmatic cowardly chap: “Ain’t one limb enough?” he tells Ahab. “What should I do without this other arm?… No more White Whales for me.”

Herman Melville is comic when he needs to be. I admit, not very often. But look to the cosmos in Moby Dick for real absurdity! Ishmael: “… man takes this whole universe for a vast practical joke, though the wit thereof he but barely discerns … [P]rospects of sudden disaster, peril of life and limb; all these and death itself, seem to him … jolly punches in the side bestowed by the unseen and unaccountable old joker.” Isn’t that last phrase an extraordinary definition of God?

13) Back on page 95 of Moby Dick there’s an appearance of “a freckled woman with yellow hair and a yellow gown,” a Nantucket innkeeper, Mrs. Hussey, who says “Get along with ye or I’ll be combing ye” to an unknown man and then, offering supper to Ishmael, asks him twice, “Clam or Cod?” Some readers take note of the colorful Mrs. Hussey, but who remembers the brief appearance of Aunt Charity “a lean old lady of a most determined and indefatigable spirit”? Sister of the co-owner of the Pequod, she’s the kindly person who brings “a jar of pickles … a bunch of quills … a roll of flannel” for crew in need.

Gregory Peck as Captain Ahab in the 1956 film version of Moby Dick.

That’s it for women’s voice and physical presence in Melville’s whale tale. Until page 706, when the ever-sober Pequod meets a ship its mirror opposite, the hedonistic partying Bachelor. We look down onto its deck to see “the mates and harpooners … dancing with the olive-hued girls who had eloped with them from the Polynesian Islands.” Back on the Pequod, Melville suppresses any expression of lust by either captain or crew. The single acknowledgment that sexuality exists is on page 757 where the ship’s carpenter notes his aversion to females: “What an affection all old women have for tinkers…. And that’s the reason I would never work for lonely widow old women ashore.”

Women when finally mentioned in Moby Dick are put on pedestals. Several times deep in the book, Starbuck speaks longingly of his wife left behind, and of his anxiety that he’ll never see her again. Her name, not surprisingly, is Mary. It’s finally on page 776 that Ahab opens up about his marriage. He lets his guard down to Starbuck and talks guiltily of “that young girl-wife I wedded past fifty, and sailed for Cape Horn the next day, leaving but one dent in the marriage pillow — wife? wife? — rather a widow with her husband alive! Aye, I widowed that poor girl when I married her, Starbuck; and then the madness, the frenzy, the boiling blood … old Ahab … furiously, foamingly, chased his prey — more a demon than a man!” In the last section of Moby Dick, Starbuck pleads with emotion for Ahab to “fly these deadly waters” and the “chase for that hated fish” so that both can return home to their domestic lives. But Ahab never again shows vulnerability as in that one conversation. The terrible white whale prevails in his consciousness over his saintly wife and son.

14) I’ve been describing Moby Dick’s peculiar sexual restraint, Melville’s decision to disallow any moment of sexual desire to be expressed by the crew of the Pequod. But that meant my passing uncomfortably over chapter 94: “A Squeeze of the Hand,” page 600-602 in my Modern Library volume. That’s where Ishmael and his shipmates are charged with taking cooled and crystallized whale spermaceti and then asked to “squeeze those lumps back into fluid.” Well, Ishmael goes at it with, I admit it, orgasmic excitement: “I bathed my hands among those soft, gentle globules of infiltrated tissues, woven almost within the hour; as they richly broke to my fingers, and discharged all their opulence, like fully ripe grapes their wine; as I snuffed up that uncontaminated aroma, — literally and truly, like the smell of spring violets…” And so on!

14) I’ve been describing Moby Dick’s peculiar sexual restraint, Melville’s decision to disallow any moment of sexual desire to be expressed by the crew of the Pequod. But that meant my passing uncomfortably over chapter 94: “A Squeeze of the Hand,” page 600-602 in my Modern Library volume. That’s where Ishmael and his shipmates are charged with taking cooled and crystallized whale spermaceti and then asked to “squeeze those lumps back into fluid.” Well, Ishmael goes at it with, I admit it, orgasmic excitement: “I bathed my hands among those soft, gentle globules of infiltrated tissues, woven almost within the hour; as they richly broke to my fingers, and discharged all their opulence, like fully ripe grapes their wine; as I snuffed up that uncontaminated aroma, — literally and truly, like the smell of spring violets…” And so on!

Is this an explosion of queer desire? Or, like Freud’s warning — sometimes a cigar is just a cigar — is this emission from a sperm whale just, well, an emission from a sperm whale? I found it hard to believe that someone as discreet as Melville — and this is the mid-19th century — would go deliriously post-Stonewall in this passage. So I passed on it.

But I was challenged by my great friend Will Aitken, who is the author of, among many fine books, his brilliant study Death in Venice: a Queer Classic. Aitken is adamant that the passage above should be read as sexually as it seems: “It’s an extended, rhapsodic passage full of rich and heavily sensual imagery. What’s going on here is a baptism by sperm, he and his fellow sailors bathing their hands in it, their hands intermingling in the rich unctuousness of it.”

As Aitken explains, prior to writing Moby Dick, Melville had “… encountered socially acceptable homosexuality when he lived on the Island of Nukakiva in the Marquesas in 1842. There he encountered a tayo, a homosexual who cared for him and shared his bed. In a number of novels prior to Moby Dick, Melville provided fictional sketches of tayo figures. In Billy Budd he has a whole ship fall in love with a Handsome Sailor. In White Jacket he refers to ships as ‘wooden-walled Gomorrahs of the deep.’ In his novel Omoo, drawing upon his experience of ‘bosom friends’ in Tahiti, he specifically refers to the ‘unnatural crimes’ of the Tahitian Prince Pomaree II.”

Everything Aitken says makes sense. But still, how could Melville put to pen something so overtly sexual/homosexual as his masturbatory sperm passages in Moby Dick? And never for even one more sentence elsewhere in his 820-page book?

Aitken, my Montreal pal, gets the final word: “I think from time to time, during a lifetime of repression, Melville sometimes burst forth and expressed his hidden passions without reserve — as in the Moby Dick passages, as in his beseeching letters to Hawthorne. His desires overwhelmed him and he let fly!”

15) I earlier noted how, after one big speech to his crew promising a nailed-down doubloon to whoever spots Moby Dick, Ahab retreats from view on the Pequod. He only comes on deck to ask passing ships if they’ve seen a white whale or to deliver an occasional opaque soliloquy. It’s very deep into the book when Ahab has his first “real conversation.” Surprising to me, it’s with the ship’s carpenter, who is carving Ahab a new wooden leg. The carpenter asks Ahab if he feels where the leg is missing, and Ahab is candid in saying that he does indeed.

After that, Ahab opens up several times in heated conversations with Starbuck, the only member of the crew who dares to challenge him. We can easily forget that Ahab was a captain-for-hire on the Pequod. It’s not his ship. He has two bosses in Nantucket who employed him to capture sperm whales and with no knowledge of his secret plan to chase Moby Dick. When the always-conscientious Starbuck reminds Ahab of his job responsibilities, Ahab pulls out a rifle and comes very close to murdering his chief mate. But a few minutes later, Ahab has one of his only tender-feeling moments, saying (apologetically?), “You are but too good a fellow, Starbuck.” We can like Ahab a bit when he unexpectedly takes the mad Black boy Pip to live with him in his quarter: “Hands off that holiness!” Does the Pequod captain have a heart? Ahab claims that he does, telling Pip, “Thou touchest my inmost centre, boy; thou art tied to me by cords woven of my heart-strings.”

But don’t get too attached to the “changed” Ahab. Soon after, he sinks morally low by refusing to help the captain of the Rachel, a passing ship, to rescue the captain’s son lost at sea. Even if Ahab has a son himself. No, Ahab can’t lose time with charity while trailing Moby Dick.

Along with “moody,” the term used repetitiously by Ishmael to describe Ahab is “monomaniac.” In the later chapters of the book, Ahab turns (this term isn’t used) flagrantly “megalomaniac.” This is the guy who says, famously, “I’d strike the sun if it insulted me.” He shouts out to his crew, “… the doubloon is mine. Fate reserved the doubloon for me. I only; none of ye could have raised the White Whale first.” And Donald Trump, trump this for executive hubris — Ahab lecturing his underlings Starbuck and Stubb: “… ye two are all mankind, and Ahab stands alone among the millions of the peopled earth, nor gods nor men his neighbors!”

Ahab uber alles.

16) Ishmael probably obsessed too much about whales, so I gather it’s time to retire my many posts about reading Moby Dick. This missive is nearly the last, patient reader, as I’ve also completed my three-week read of Melville’s 822-page novel. A very good book!

Let’s talk about the titular character. There’s the famous delayed entrance of Moliere’s Tartuffe in his same-named stage comedy. It’s only on the last two pages of The Charterhouse of Parma that Stendhal tells us what the title means. And it’s not until page 781 of my Modern Library edition of Melville, after two-and-a-half weeks of my reading, that the much talked-about white whale makes his first dramatic appearance. The sighting is by Ahab himself, who “raised a gull-like cry in the air, ‘There she blows! — there she blows! A lump like a snow-hill! It is Moby Dick!'”

Now that he finally surfaced: what is the nature of this white sea creature? Is he just another rotten-tempered sperm whale as some in the book have contended, including Starbuck, though larger and therefore fiercer? Or is he some daemonic creature with his eyes and brain and teeth consciously aimed at destroying Captain Ahab, which Ahab ardently believes? Well, here is how the living Moby Dick is delineated in the narration: “A gentle joyousness — a mighty mildness of repose in swiftness invested the gliding whale … as he divinely swam…. [T]he grand god revealed himself, sounded, and went out of sight.” And when breaching,”… the White Whale tossed himself salmon-like to heaven.” Far from daemonic! The opposite of daemonic. In the many pages of Moby Dick being described in the flesh, I uncovered only two negative adjectives: “maliciousness” and “devilish,” but neither are dwelled upon. Beautifully ambiguous is this key sentence: “Moby Dick seemed combinely possessed by all the angels that fell from heaven.” Angels still angels? Or angels now in Lucifer’s grip? Take your pick. Here’s my eco-view: Moby Dick is no satanic animal, just a smart, strong sperm whale who correctly fights back when he is attacked by Ahab and the Pequod. You might even root for him!

A Rockwell Kent illustration of Moby Dick. Photo: courtesy of Plattsburgh State University.

There’s no ambiguity with the irreligious Ahab, who not only stands up to God but comes to regard himself as an alternative to God. It’s Starbuck who challenges Ahab’s compulsion to kill the white whale as being insanely non-Christian: “Great God!… In Jesus’ name no more of this, that’s more than devil’s madness…. Impiety and blasphemy to hunt him more!” As the Pequod sinks to Davy Jones’s locker, a “bird of heaven” is pulled underneath also because “…Ahab went down with his ship which, like Satan, would not sink to hell till she had dragged a living part of heaven with her…” Satan, “sink to hell.” It’s not the white whale who is in Lucifer’s domain.

Where’s Ishmael in all this? Do you realize that Ishmael and Ahab never share a word in the entire novel? If I may criticize Melville, it seems to me a mistake that Ishmael completely disappears from the narrative in the last several hundred pages, including in the three-day battle with Moby Dick. (And where are Queequeg and Pip? I missed them also.) Who takes over telling the story? Is it the omniscient author? Or a suddenly meek, subdued Ishmael? The poet Charles Olson warns, “Too long in criticism of the novel Ishmael has been confused with Herman Melville himself.” I’m not so sure. I need a theorist of narrativity to elucidate.

Anyway: SPOILER ALERT. In case you were worried: Ishmael did not drown with all the others, as “the great shroud of the sea rolled on as it rolled five thousand years ago.” He makes a glorious first-person return on the last page of the book. Hip hip hooray, Ishmael celebrates, “because one did survive the wreck.” Interestingly, he credits his remaining miraculously alive to “the Fates.” Sorry, God!

17) P.S. “One of the biggest disappointments of my career was when the critics and the public did not respond to Moby Dick,” John Huston said in a 1980 interview. “They took it out on Gregory Peck, which I think was unfair, because I liked him and I liked the film. Still do…. I think that Greg is quite remarkable.” I just watched the 1956 movie and mostly agree with Huston. It’s not a great film but a very decent and intelligent one. There’s a smart and literary-minded script by Ray Bradbury, which leans mostly on words from Melville himself. As for Gregory Peck: he starts out a little too gentlemanly but he becomes a deeper, darker, more malevolent Ahab as the Pequod gets closer to Moby Dick. And he’s splendid delivering several stormy soliloquies shot by Huston in extreme closeup. Interestingly, Huston chooses to show Ahab as having a MAGA-grip on his crew, who are mesmerized by his bullying charisma and willing to follow him down the most destructive paths. Ishmael too! Starbuck stands by disbelieving, impotent, like a 2025 liberal.

Quickly, what’s cut out? There’s no Nantucket. The Pequod sails out of New Bedford. There’s no problematic cuddling in bed with Ishmael and Queequeg. Ahab has no wife and child. Ishmael doesn’t lecture us at all about whales. He’s presented as an ex-merchant mariner who knows literally nothing about cetology before signing up on the Pequod. What’s added? A potent scene in which Starbuck tries to get the other officers to join him in mutiny. Nope. They adore Ahab, whatever he does. Unlike the novel, screenwriter Bradbury arranges for Ishmael and Ahab to have an actual scene together. The script has Ishmael confront Ahab with the prophecy of an old sailor, Elijah, that Ahab will take his ship down.

What will bother a modern audience? Huston seems to have no problem with whale hunting, as exhilarating music plays over scenes in which whales are slaughtered, creating a red sea.

An unintended mystical numerological moment? Ahab appears on deck for the first time at minute 33:33. Any women in the film? Some badly directed female extras are asked to look sad in the harbor as the Pequod sails away. One Christian woman with a line: “Bibles!” And some flagrant political incorrectness: an Austrian count who was Huston’s friend was cast as the “savage” Queequeg. To me, he’s great!

19) P.S. When I was in high school, I actually took a typing class and the teacher’s name was … Miss Shmael. No, she did not start the class by saying, “Call me Miss Shmael.” There’s a famous story that Harold Ross, the first editor of The New Yorker, leaned in the door and queried the fact-checkers one day, “Is Ahab a person or the whale?”

Gerald Peary is a professor emeritus at Suffolk University, Boston; ex-curator of the Boston University Cinematheque. A critic for the late Boston Phoenix, he is the author of nine books on cinema; writer-director of the documentaries For the Love of Movies: The Story of American Film Criticism and Archie’s Betty; and a featured actor in the 2013 independent narrative Computer Chess. His last documentary, The Rabbi Goes West, co-directed by Amy Geller, played at film festivals around the world, and is available for free on YouTube. His latest book, Mavericks: Interviews with the World’s Iconoclast Filmmakers, was published by the University Press of Kentucky. With Amy Geller, he is the co-creator and co-host of a seven-episode podcast, The Rabbis Go South, available wherever you listen to podcasts.

Gerald speculates on Edgar Allan Poe’s influence on Moby Dick. But there is stronger evidence that James Fenimore Cooper might have had some sway. Melville gave a positive review to Cooper’s 1849 novel The Sea Lions, an allegorical sea yarn in which two vessels – headed by captains with morally opposed natures — race toward the Antarctic. I read The Sea Lions decades ago, and remember it fondly as one of Cooper’s best, an action-packed sea yarn. As Melville wrote, the narrative is filled with “many narrow escapes from icebergs, ice-isles, fields, and floes of ice.” And there’s a terrific ending: the crew of one of the ships is found — most of them frozen to death. Great stuff …highly recommended for those who love 19th century sea fiction. Melville began Moby Dick in 1850.

Melville’s verdict on The Sea Lions: “Upon the whole, we warmly recommend the Sea Lions; and even those who more for fashion’s sake than anything else, have of late joined in decrying our national novelist, will in this last work, perhaps, recognize one of his happiest.”

I’ve never read The Last of the Mohicans but maybe Chingachgook and Uncas, the novel’s title characters, were an influence on Queequeg. Who knows?

Could be — but there is no doubt that Cooper’s sea fiction was an influence on Melville’s. Cooper invented the genre, after all. A Library of America volume has two of Cooper’s popular sea yarns — The Pilot and Red Rover. The Sea Lions — an allegorical seafaring yarn — should have been included.

Also, the one novel ofCooper’s I would recommend would be The Last of the Mohicans — a fast-paced adventure (for him) with mythic trappings.

Thanks for this informative, evocative report on reading Moby Dick. It makes me ALMOST ready to crack the thing open….

Do read the great book. It won’t bite you. It’s very tasty.

Barrymore appeared in a silent version in 1926, “The Sea Beast,” which almost travesties Melville. Ahab’s obsession is caused by his dastardly brother, who pushes him overboard into the whale’s jaws so he can steal Ahab’s beloved. Barrymore’s ghost-written autobiography, “Confessions of an Actor,” published before the film’s release, declares that since the novel has no love interest, “Ahab will probably fall in love with the whale.” It was a big hit, not so much the sound remake in 1930. Barrymore’s co-star in “The Sea Beast” was Dolores Costello, with whom he fell passionately in love. There is footage of the two in a kissing scene that goes on long after the director frantically signals, “Cut!” (Obviously a publicity stunt, but endearing).

It was good to read your adventures with “the Whale” all in one place, especially because I missed a few Facebook posts. I especially appreciated the bit from Prof. Aitkin on Melville’s sexuality….. Minor quibble: You got the title wrong, “It’s Moby-Dick, or THE Whale” (emphasis mine)…. And, yeah, don’t forget the hyphen…. For a fictional treatment of Ahab’s neglected wife, see the highly regarded “Ahab’s Wife,” by Sena Jeter Naslund. In my reading of your reading, it’s Melville who neglects her, not Ahab. Not a story he was interested in telling — or had room for, I guess. Also, just because there’s no mention of Ahab sending the wife money, there is no evidence that he did not. Just because it’s not in the book doesn’t mean it didn’t happen. Or: don’t confuse the character and the author by criticizing the character for something the author didn’t write. (American Lit 101, as you chastised me!) As for the shifting point of view from the first-person to general omniscience. I think Melville didn’t care. He was off on his Nantucket sleigh ride of a book, shifting style and tone at every turn. (I forgot that there was a little play in the middle of it.) So yeah, he forgot about the wife — he had bigger fish to fry! And sperm to milk!…. Anyway, congrats! And now onto “Don Quixote” — were the Don and Sancho Panza gay lovers? Go for it!

The Pequod never docked in the book so no Ahab sending money to his wife. Deadbeat dad all right as it was Ahab who decided to keep the ship always at sea chasing Moby Dick.

Lest we forget, Bildad’s concern, as well: “But thou must consider the duty thou owest to the other owners of this ship- widows and orphans, many of them…we may be taking the bread from those widows and those orphans.”