Book Review: A Puzzling Look at the West, Islam, and The Convert

By Roberta Silman

If you are going to write about this very charged subject, the West and Islam, why would you choose as a representative of that great and ancient culture a woman who is stunted emotionally, clearly unreliable, and probably mentally unstable?

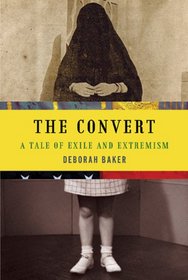

The Convert, A Parable of Islam and America by Deborah Baker. Graywolf Press, 256 pages, $23.

Biography can be a tricky business, and when dealing with a subject as elusive and strange as Maryam Jameelah, you are probably better off choosing to write something that is not a straight account. But what we have here is a biography that is as confusing as many of our feelings in this country are about Islam.

Perhaps that was author Deborah Baker’s intention, for she is an experienced author of three earlier books, biographies of Robert Bly, Laura Riding, and the Beats in India. And there are those who believe the unconventional approach is successful: glowing blurbs for The Convert as a well as a starred review in Publisher’s Weekly.

Yet, I felt that in her effort to create a metaphor for our attitudes toward Islam, which have been so reshaped in this first decade of the 21st century, she has made the story more convoluted than it needed to be.

We begin with three letters from 1962: first from Mawlana Abul Ala Mawdudi who is inviting a young woman to come live with him and his family in Lahore, Pakistan, then a letter from the young woman’s father, Herbert Marcus, thanking Mawdudi for the invitation, and finally, a letter from the young woman, Margaret Marcus, called Peggy by her family, who was born in 1934 and has finally found an escape from her home in Westchester County in New York State to live in the land of her dreams and become a Muslim.

Then Baker insists, “Anonymity is my vocation.” No one who is a writer is anonymous; that is exactly what we writers are not. And if she means by that statement that she wants the story to speak for itself, she does not even let that happen. Moreover, I find it hard to believe that she came across Maryam Jameelah entirely by chance. But once she finds those boxes of letters and drawings that were donated by Jameelah to the New York Public Library, she tells us that “Like many children, I had once been haunted by big questions, Who created us? What is it to be good? Is there life after death?” and then decides that “Margaret’s life goes straight to the heart of a heated debate over the notion of a divide between Islam and the West.”

Ten pages later, as a kind of answer as to why Margaret’s life took the turns it did, she describes an incident when year-old Margaret is haunted by the sight of black people at the back of the bus in Savannah, Georgia. This comes off as simplistic: a lot of kids Margaret’s age were haunted by the divide between black and white in this country in the 40s and 50s, and they became activists in the civil rights movement, liberal democrats, and helped propel Barack Obama to the presidency of the United States.

But how did a child born in 1934 to Jewish parents in the suburbs of New York City come to be the writer of over 30 books on Islam named Maryam Jameelah? It took me a while to untangle the personalities involved because, Margaret/Maryam is a slippery character and has doctored some of the letters, removed others, and is capable of lying when it suits her.

Peggy was a difficult child, a late talker, unpredictable, socially awkward, subject to fits of temper, a wonderful artist, and by pre-adolescence in love with all things to do with the east, utterly contemptuous of the western values that her parents espoused, and a trial to both her parents who clearly didn’t know what to do with her.

When Israel was declared a state, she said, baldly, “I no longer consider myself a Jew.” Although she was considered odd in grade school and high school, she managed and even went to NYU for a year. But after she was asked not to return and suffered a breakdown, the story becomes heartbreaking.

In a search for answers about this young woman, schizophrenia was a possibility although there was no definite diagnosis; then began the visits to psychiatrists (one was the eminent Lawrence Kubie), the electroshock treatments, stays in New York Hospital in White Plains, and, finally, after her parents had exhausted their funds, incarceration in the Hudson River State Hospital in Poughkeepsie. Everyone, even her Aunt Helen, with whom she could achieve a measure of contentment, was at a loss.

So when Peggy decided to emigrate to Pakistan and received an invitation in 1962 to live with Mawdudi, a well-known thinker and writer of the Islamic world, of course she went, with hopes of beginning again. The saddest thing is that her life wasn’t much different there. After an unsatisfactory time with Mawdudi and his family, where she seemed to generate the same kind of pandemonium she created in her first home, she was eventually married off, had children who seemed to give her “absolutely no joy” (her words), wrote her books that seemed to inspire scores of young jihadists, and is now living alone in Lahore.

In 2007 Baker went to Lahore, met with Mawdudi’s son Haider Farooq, and eventually met with Maryam. Some questions were answered; some were not. When she wanted to know about Maryam’s marriage, this was the response:

“Why?” Haider Farooq asked, a note of rising disbelief in his voice, as if I was about the most foolish woman he had ever come across. A torrent of Urdu ensued, and his eyes flashed in my direction. I felt pinned to the chair. Ali translated a gentler version. “Because Yusuf Khan imagined he could make a lot of money off her book” he said laconically. “Get his children into the U.S. and live over there, start educating over there. That was the only reason. Nothing like love.”

That exchange is emblematic of how some of Baker’s assumptions seem to be off, or go awry. But my question about this book goes deeper. If you are going to write about this very charged subject, the West and Islam, why would you choose as a representative of that great and ancient culture a woman who is stunted emotionally, clearly unreliable (e.g. her views on the place of women in society), and probably mentally unstable?

My suspicion is that once Baker got into this project, she couldn’t let it go, and I understand how her basic compassion led her to pursue such a disturbing story to its conclusion. Yet I cannot help but think that those of the Islam faith will be offended by its basic premise. Moreover, at its end this story simply peters out, and we are left with Jameelah posting entries on the internet, then removing them. Hardly the resolution of “the heated debate” that first propelled Baker to write this puzzling book.

Roberta Silman is the author of Blood Relations, a story collection, and three novels: Boundaries, The Dream Dredger, and Beginning The World Again. She can be reached at rsilman@verizon.net.