Book Review: Of Childhood and State Terror

Set in the beginning of the “Dirty War” of Jorge Rafael Videla’s military junta in Argentina, a period characterized by assassination and disappearance, “Kamchatka” is a superb novel that refracts public, political events through the sensibilities of everyday life.

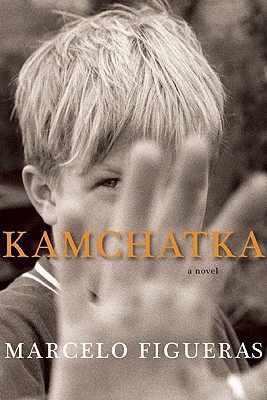

Kamchatka by Marcelo Figueras. Translated from the Spanish by Frank Wynne. Black Kat, Grove/Atlantic, 311 pages $14.95.

By Jim Kates

The book you come on by chance, even by mistake, is the one that finds you—the chance encounter—not by you finding it or searching it out, a real discovery. So I washed up on Kamchatka‘s shore. My local, independent bookseller (Willard Williams of Toadstool Books, Peterborough, New Hampshire) tossed the book to me from his slush pile of uncorrected galley proofs—a book not yet officially published, but distributed for publicity purposes.

“Here,” he said, knowing my professional interests, “something Russian for you.”

It was the kind of fortuitous transaction that could never take place with an online ordering behemoth or in a big-box-bestseller store.

Especially because my bookseller was wrong. There is nothing at all Russian about Kamchatka, in spite of the title.

Geographically, it’s set as far as possible on the other side of the world, in Buenos Aires, where “Kamchatka” has another meaning: “I can’t remember a time when I did not know about Kamchatka,” writes the narrator. “At first, it was simply one of the territories waiting to be conquered in Risk, my favorite board game, and the epic sweep of the game rubbed off on the place-name, but to my ears, I swear, the name itself sounds like greatness. Is it me, or does the word ‘Kamchatka’ sound like the clash of swords?” And, at the very end of the novel: “Kamchatka was the place from which you fought back.”

Swords clash offstage in Kamchatka. Figueras’s narrator transports us to the beginning of the “Dirty War” of Jorge Rafael Videla’s military junta, a period characterized by assassination and disappearance. The oppressive rule of the junta has killed “Tío Rodolfo,” a political associate of Papá, early enough to warn the family of four to “go on a holiday I didn’t want to go on,” into protective hiding. (Papá has been a defense lawyer, Mamá a politically active professor.) They have taken false names (the narrator names himself after Harry Houdini, an escape artist) and live an existence on the outskirts of their former life.

There is a kind of novel that refracts public, political events through the sensibilities of everyday life. The “important” events take place in an unseen, large world, but their actual import resonates inside the stories we are told. Thus, for instance, Jane Austen’s Persuasion is a novel as much about the changing status of the British navy as it is about a tense romance. Kamchatka leads us deep into the heart of Argentinian terror without expressing that terror in any more than seemingly mundane details:

These and other bits of information filtered back to me, but only fragments, pieces of a jigsaw puzzle I couldn’t put together; I was so much in denial that I didn’t even have nightmares. For a long time I thought that my parents told me these little things because they believed I wouldn’t understand the bigger picture—whatever it was they were not saying, whatever they were hiding from me. Now I think they did it deliberately, knowing that by the time I put the pieces together and could finally see the picture in the jigsaw puzzle, I would be safe, far from the danger that, right now, threatened us all.

Figueras has filtered the perception of a a grown-up story through a child’s perspective. “When the coup d’état came . . . I knew straight off that things were going to get ugly. The new president had a peaked cap and a huge moustache; you could tell from his face that he was a bad guy.” In 81 anecdotal chapters so short they seem to be geared to the attention span of a 10-year-old but with the sophistication of Herman Melville, who gives the book its epigraph—”It is not down on any map; true places never are”—the story moves forward inexorably to the personal consequences of political oppression. Frank Wynne’s (British English) translation carries the authority of the original, with the balance of adult understanding and a child’s interests and anxieties. The language mediates between the two. Think not Melville, but the Mark Twain of Huckleberry Finn, yet starring a Huckleberry Finn who has read Melville.

The Harry who narrates his story delights in ruminative essays and pronouncements, brief essays that frame events. “Words, like all things, exist in time,” begins a chapter entitled “This Year’s Model,” which is devoted to a key discussion of fathers and fatherhood, coming only in its last two paragraphs to Harry’s own father and grandfather.

As much as Kamchatka is about politics, it is about Harry’s family, too, and a definition of family that expands beyond the nuclear into community. Harry’s world is defined by his father, mother, and his little brother the Midget, his grandparents, and a slightly wider circle of friends and teachers—such as enter inside a 10-year old’s horizon and then wave goodbye and drive off.

You may have already guessed the story’s conclusion—the inevitable conclusion of such a story set in such a time and place. “I only am escaped alone to tell thee . . . It was the devious-cruising Rachel, that in her retracing search after her missing children, only found another orphan,” you might quote what was written of others who disappeared at the end of Moby-Dick,” but Harry doesn’t. Instead, “I’m not Harry [the escape artist] at least not now. I don’t perform escapes any more.”

Kamchatka came to me by chance. Don’t trust to such luck. Seek it out.

===========================================

J. Kates is a poet and literary translator who lives in Fitzwilliam, New Hampshire. He helps run Zephyr Press.

Thanks for that – a very lovely review that gets to the heart of a book I’m very proud to have worked on.

Dear J.,

I’m really moved by your wonderful review. Thanks from the bottom of my heart. And please extend my gratitude to Mr. Williams, without whom this miracle wouldn’t have happened.