Theater Commentary: Tennessee Williams — Putting What is Inexpressible in Life into Words

Davis Robinson, artistic director of the Beau Jest Moving Theatre, shares his thoughts about Tennessee Williams on the 100th anniversary his birth. The company’s 2009 production of the playwright’s late drama The Remarkable Rooming House of Madame Le Monde illuminated a neglected side of the playwright’s genius.

By Davis Robinson

When we started working on The Remarkable Rooming House of Madame Le Monde, two wonderful research opportunities came up.

First, I spent a couple days at the Harvard Theater Archives, where there were some early, typewritten versions of the script, with corrections and changes made by Tennessee. Not only did the archives help illuminate the play for me, it gave me a tremendous amount of respect and empathy for the life-long, contradictory struggles Tennessee endured to the bitter end. His first 20 years of phenomenal commercial success actually helped mask what an experimental and forward-thinking playwright he had always been, and researching Le Monde helped me see all of his work in a new light and reject the narrative of the dramatist as a washed-up has-been who lost his touch in his later years.

I started reading all of the postcards and letters in the collection, from the 1930’s until a month before he died. In one folder was his first postcard from Provincetown to his grandfather Dakin saying, “This is the most delightful summer place I have ever been. I’m living on the wharf you see here—picture at low tide. Excellent swimming right out front yard. Delicious seafood and a lot of entertaining people.” And in the next folder, a letter to his mother saying, “I am sorry you didn’t like the plays,” or a letter to a friend pleading not to give up on him for his cruel behavior.

Box after box echoed this passion for life, this vicious ability to lash out, an amazingly poetic and precise use of language, and a desire to get up every day and write “like that King of the Orient who kept building and building his palaces and gardens till they became grotesque because a fortune teller told him he would die when he stopped” (in a letter to his friend Jay in 1960 regarding the opening of Night of the Iguana).

The second revelation was meeting John Uecker, Tennessee’s secretary in those final years, who typed the manuscript for Le Monde that I read at Harvard and who was with Tennessee in the hotel when he died. We talked all day in his apartment in New York and later at the festival in Provincetown when we presented the piece.

He had some wonderful insights, believing that Madame Le Monde was very clearly a caricature of Marie St. Just, a best friend who betrayed Tennessee in his later years. And that the relationship between Mint and Hall echoed the betrayal Tennessee felt from Gore Vidal and others who abandoned him, as if he were hanging in an attic watching others lick up the final crumbs and hand him an empty plate.

John had some great anecdotes and some wonderful insights into the playwright’s wry sense of humor, which is still present, quite darkly, in The Remarkable Rooming House. I found it a very moving piece, with that characteristic touch of poetry at the end when Le Monde gazes at the moon saying, “ The moon is out, serenely. It goes, it goes. There’s nothing more to be asked for that will ever be given.” Naturally, she’s murdered everyone.

And then I found a letter Tennessee wrote to his friend Jay (James Laughlin, an editor at new Dramatists) in 1942 that really says it all. “The plot is a coat-hanger for the verse, and the verse is a coat hanger for the passages of really intense and good poetry. All my best poetry is tucked away in long and short plays: like bonfires of lyrical talk that spring unexpectedly…much to the distress of commercial producers who prefer the raw beef of action and plot which one has to fling at them.”

I think the four characters in Le Monde capture some of the most basic archetypes in Tennessee’s work. In a way, it is a prism to four sides of his own personality. The domineering mother from hell; the wounded/cripple in need of help and understanding; the sexy, male, macho lover; the mysterious stranger capable of pointless brutalities couched in a poetic landscape as real as something by Beckett or Ionesco. Looking through his letters and reading how much he loved and how much he hurt those around him, I saw how much Tennessee was in each part. And when playing any one of these roles, it is a tremendous help to each actor to see a bit of those other traits in each of them.

David Kaplan, curator of the Provincetown festival, has some wonderful events planned this year and a newly-edited book called Tenn at One Hundred that I am looking forward to reading. I am glad to see that critical opinion on Tennessee is starting to shift as we celebrate his 100th birthday.

1970’s Green Eyes got a great review in the New York Times last month, and John Lahr wrote a New Yorker article that affirms the value of re-examining Tennessee’s experimental work.

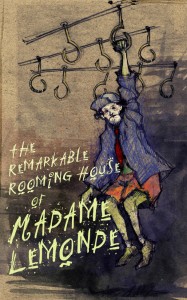

A scene from the Beau Jest Moving Theatre production of THE REMARKABLE ROOMING HOUSE OF MADAME LE MONDE.

We at Beau Jest began to read a number of one-acts for a possible pairing with Le Monde to make a full-length, macabre evening, which we may do at some point, but we aren’t going to do anything with it this year. I think we’ll just be an audience for other Tennessee Williams shows around the country while we prepare for our next show, Aristophanes’ The Birds, premiering in Boston in 2012.

While doing research, I did become obsessed with the original version of Camino Real. Talk about poetic with no plot! Its a lovely, mysterious, allegorical play that deserves a full production. I think the world is more ready for it now, in all its fractured and mysterious beauty.

When it was put on Broadway, the original Ten Blocks became Sixteen, and all the poetry and beauty of the original collapsed under efforts to make it a more palatable commercial play. I think Beau Jest will be able to realize his original vision, right down to the gaudy flowers made of tin and the violets breaking through the rocks in the mountains, with guitar music wafting through the plaza and street sweepers mopping up the dead, but it is going to take a while. Not a lot happens in terms of plot and action, so we’ll need to educate the audience beforehand as to what kind of world they will be entering.

But it’s one that I think deserves to be seen, with the right actors and the right designers. Maybe site-specific in Greece? I hope to do it within the next five years, and if anyone else gets to it first, more power to ‘em. I’d really like to see it come to life as he dreamed it.

Happy Birthday, Tennessee, and thanks for putting so much of what is inexpressible in life into words.

You are one of those courageous ( i.e. immensely talented) directors of whom I was thinking when I wrote my piece on Tennessee Williams.

I did not realize that you had staged his remarkable “rooming house,” and I sure wish I had known about it at the time.

Best future with all your work,

Joann Green Breuer

Thanks for your kind words, Joann. I’ll let you know when we are doing anything Tennessee-related in the future.

I just read David Kaplan’s new book Tenn At One Hundred, and it has some great essays that helped convince us that…DRUMROLL…Ten Blocks On The Camino Real will be our next show. Look for it in spring, 2012. You heard it here first!