Book Interview: Natsume Sōseki — A Century After the Death of a Literary Giant

“Natsume Sōseki once wrote a letter of encouragement to a younger writer, telling him that the true value of a literary work isn’t known until a hundred years have passed. If that’s correct, then maybe finally we’re reaching the Sōseki moment in the English-speaking world.”

By Bill Marx

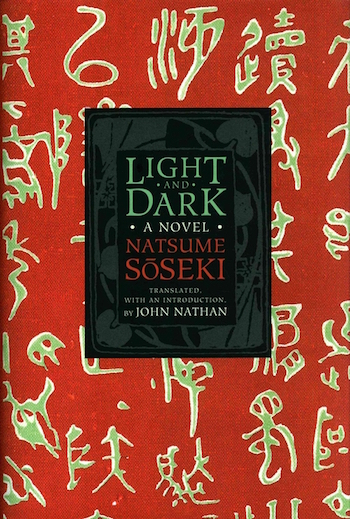

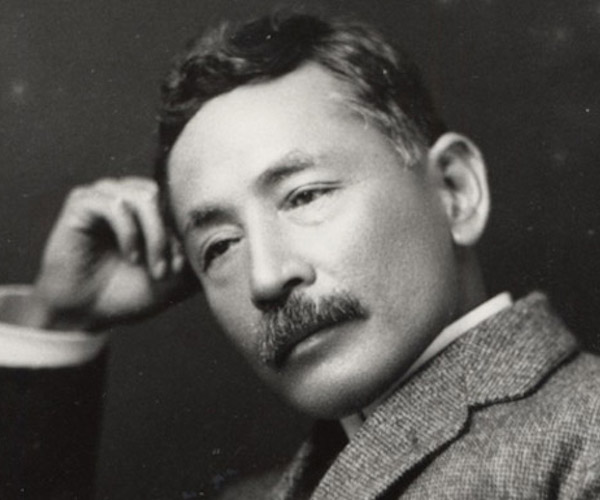

A hundred years ago today one of the major writers of the 20th century, a giant of Japanese literature, died from stomach cancer at the age of 49. Natsume Sōseki didn’t live to complete his final (and longest) novel, Light and Dark, which he was publishing in daily installments for his employer (since 1907), the Asahi newspaper. Head-spinning proof of Sōseki’s stature in Japan — and the country’s hyperbolic esteem for its writers — comes in the form of a “robotic replica” of the author, which was unveiled yesterday at Tokyo’s Nishogakusha University. The android, via the voice of manga columnist Fusanosuke Natsume, the grandson of the writer, recites passages from the Sōseki volume Ten Nights of Dreams and responds to questions. “Long time no see, everyone,” jokes the artificial man. “It’s been about 100 years, has it not?”

What is all the fuss about? Through a series of novels, beginning with the comic tomes 1905’s I am a Cat and 1906’s Botchan, the author created stories and characters that probed — with tragic intensity — the bedeviling self-consciousness, moral ambiguity, and fragility of contemporary human relationships. The result is a fearless, at times experimental, and visionary dissection of the insecurities generated by the pressures of modernity, beginning with 1906’s The Three-Cornered World: “An artist is a person who lives in the triangle which remains after the angle which we call common sense has been removed from the four-cornered world.” I discovered that magic triangle back in the early ’80s by way of a series of translations from Perigree Books. Since then I have not stopping reading and re-reading Sōseki, eagerly taking up any new translations as they came along, most recently New York Review Books’ The Gate and Columbia University Press’ Light and Dark.

Why isn’t Sōseki better known here? I am at a loss to explain why this genius remains so under appreciated. There are obvious Western influences on his work: he spent some years in England and admired Jane Austen and Henry James. So, on the 100th anniversary of the writer’s death, I turned to Michael K. Bourdaghs, professor of modern Japanese literature at the University of Chicago, to explain the neglect. In his responses, Bourdaghs mentions Sōseki’s resonance with Kafka, Gertrude Stein, and Virginia Woolf. Those interested in that modernist connection should turn to 1908’s The Miner, an amusing exercise in flyblown absurdity (a forlorn character attempts to think himself out of existence) that would have left Samuel Beckett chuckling. It is my personal favorite among his novels.

Arts Fuse: You and your co-editors Atsuko Ueda, and Joseph A. Murphy claim in the introduction to Theory of Literature and Other Critical Writings that Natsume Sōseki is one of the most important authors of the twentieth century “whether of Japanese or world literature.” Why do you believe that to be true?

Michael K. Bourdaghs: You have to start with the brilliance of his writings, of course. As a novelist, Sōseki’s career lasted little more than a decade, but in that time he produced an astonishing string of works that in Japan are both enormously popular and critically celebrated—a rare combination. Beyond that, he gives us a rare voice from outside Europe or North America who shared in the experience of twentieth-century global modernity, but also knew intimately another world. It’s always pointed out that he belonged to the last generation to receive its primary education in the older Sinocentric model of learning. This meant that for Sōseki there was nothing natural about the modern—and yet it was also the world he and his characters occupied. He captures with great insight the sense of alienation that haunts us in the modern age, that sense of unreality, of not quite belonging to the world in which we live.

He also carried out many creative experiments with literary form. You see this especially in his early stories, but it’s also very much present in the later novels. On top of everything else, he was an important literary theorist—one of the first to attempt to tackle the problem of ‘world literature’ using methodologies from both sociology and cognitive science.

AF: In Japan, Natsume Sōseki is a literary giant — but he is not nearly as well known in this country. Why do you think that is, given his stature. Are there particular reasons for this lack of interest in America?

Bourdaghs: The first Japanese novelists to have an impact in America showed up in the late 1950s: Tanizaki Jun’ichiro, Kawabata Yasunari, and Mishima Yukio. Those writers (sometimes self-consciously) presented an image of Japanese culture that answered well to the desires of American readers to find an exotic, sexy, but not too threatening, other culture. This was during the Cold War, of course, and its heady mixture of anti-communism with celebrations of global cultural difference, what Christina Klein calls “Cold War Orientalism.”

Sōseki didn’t play that game. In fact, even at the beginning of the twentieth century he seems to have detected it and rejected it—I’ve written about his rather cool attitude toward Rabindranath Tagore, for example. As a result, he wasn’t all that interesting to the first generation of postwar translators of Japanese fiction. Edwin McClellan’s translation of Kokoro (1914) appeared in 1957, but we had to wait until the 1970s and ’80s for most of Sōseki’s work to come out in English.

Sōseki once wrote a letter of encouragement to a younger writer, telling him that the true value of a literary work isn’t known until a hundred years have passed. If that’s correct, then maybe finally we’re reaching the Soseki moment in the English-speaking world.

Natsume Soseki — He captures with great insight the sense of alienation that haunts us in the modern age, that sense of unreality, of not quite belonging to the world in which we live.

AF: Sōseki spent two miserable years studying in England at the turn of the century. How did that experience shape his novels (which were written between 1905-1916)? He was an admirer of Jane Austen, Henry James, and George Meredith. Sometimes his pictures of weak men and strong women remind me of Edith Wharton.

Bourdaghs: The years in London were certainly crucial to him, even though he was reluctant to go and was terribly unhappy while there. He knew the writers you mention well, and many others, too: Joseph Conrad, William James, Henri Bergson, Baudelaire, etc. I’m always struck with how contemporary he was to his counterparts in Europe. When you read Soseki, you always find yourself drawing links to writers like Kafka, Virginia Woolf, Gertrude Stein. If anything, he was ahead of his time.

As a scholar, his specialty was late eighteenth-century British literature, but he knew the full canon quite well. One of the quirks that has often been pointed out is his apparent affinity for women writers: Austen, but also the Brontes and George Eliot. And, yes, the gender politics of his fiction are quite interesting. Many of his stories revolve around triangles in which two men compete for ‘ownership’ of a woman, but those female characters are always given their own autonomous voices in the stories. I like the Edith Wharton comparison very much.

AF: All of Sōseki’s novels are available in English, the most recent a new translation (from Columbia University Press) of Soseki’s final novel, Light and Dark by John Nathan. Have earlier English translations stood in the way of our appreciating Sōseki’s genius? Is he particularly difficult to translate? Are new translations, such as Nathan’s and William F. Sibley’s of The Gate (New York Review Classics) needed?

Bourdaghs: The new wave of translations over the past decade is quite welcome. I don’t know if I’d say the early translations stood in the way of our appreciating Sōseki. They were, after all, my own first entryway into his world. But they were produced for a different audience with different expectations. They often effaced elements that seem crucial today. For example, J. Keith Vincent has written about how McClellan’s 1957 translation of Kokoro downplayed the powerful homoerotic currents that run throughout the novel.

Some elements of Sōseki are hard to translate. His early works retain powerful echoes of earlier Japanese and Chinese narrative voice that are difficult to convey in English. And in his later novels, he was a brilliant stylist, especially when exploiting the rhetorical possibilities that opened up with the combination of Chinese characters and Japanese syllabary. But I also think that his plots, characters, and themes do translate well into other languages, including English.

By the way, Sōseki’s first newspaper novel, The Poppy, still isn’t available in English translation. So we need that, and we need multiple translations of all of his major works, I think. Would we be satisfied with just one English version of Kafka or Dostoevsky?

The 1000 yen note (the smallest paper currency unit in Japan at the time) that was in use from 1984-2004. It’s a striking statement of the cultural position Sōseki holds in Japan: they put his face on the money.

AF: In his introduction to The Gate, Pico Iyer sees Sōseki as both a conservative and a rebel, “an anxious, passive, and haunted character” whose sensitivity to the pain suffered by the isolated self — doomed to remain unassuaged in a modernizing Japan — anticipates the writing of Haruki Murakami. Do you agree?

Bourdaghs: In general, I agree—but I’d also point out that something similar has been said about Sōseki and virtually every major modern writer in Japan, as well as others from across East Asia, like Lu Xun. There is something captivating about Sōseki that makes us want to link him to other writers that have made an impact on us.

AF: What are your favorite Sōseki novels? And why?

Bourdaghs: I could make a solid case for six or seven different titles. But let me chose the one I encountered first. I’ve written about this before, but I first stumbled onto Kusamakura (also translated as The Three-Cornered World) as an undergraduate back in the mid-1980s, and it simply blew me away. It’s an early work, first published in 1906, and it’s one of his most experimental pieces. He called it his “haiku novel.”

Very little happens by way of plot. Instead, we get a kind of stream-of-consciousness meditation on the meaning of art, life, and literature as the protagonist wanders through a rural hot springs resort and interacts with the locals. There’s something about the worldview, about the radically experimental nature of the structure, and about the various characters, that just spoke to me. I like teaching the novel to undergraduates. About one-third hate it, about one-third are puzzled by it, and the remaining third find it the most interesting book they’ve ever read.

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of The Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Tagged: Columbia University Press, John Nathan, Michael K. Bourdaghs, Natsume-Soseki

From Michael K. Bourdaghs, who is currently in Tokyo for a conference on Soseki:

Met the android today (together with Soseki’s grandson, who supplied the voice samples). Odd experience: you start out feeling quite alienated, but as he continues to speak you discover yourself having moments where you forget that he’s a machine and start responding to him as a human.