Fuse News: H. L. Mencken — Banned in Boston, 89 Years Ago Today

By Bill Marx

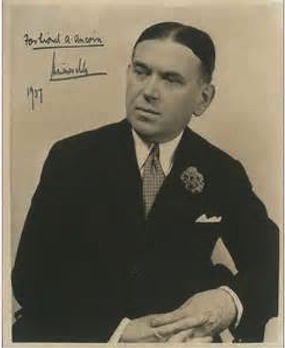

H. L. Mencken — defender of free speech.

The culmination of writer and editor H. L. Mencken’s robust crusade for freedom of speech took place on this date eighty-nine years ago, when he was arrested for selling a copy of the censored issue of his magazine the American Mercury to the Reverend J. Franklin Chase, head of the Watch & Ward Society, in the Boston Common. (The offending article was about a prostitute called “Hatrack,” who plied her trade in Farmington, Missouri.) The next day a local judge dismissed the charges, unable to see how public morals had been compromised. Today’s Mass Moments takes note of the anti-censorship fracas.

“Every censorship, however good its intent, degenerates inevitably into the sort of tyranny that the Watch & Ward fanatics so long exercised in Boston,” commented Mencken before he headed up to the city to be nabbed. James M. Cain, after he heard about the acquittal, wrote Mencken: “How you keep out of jail is a mystery to me.”

The Watch & Ward Society didn’t give up. According to Marion Elizabeth Rodgers’s Mencken: The American Iconoclast, Chase went to Washington, D.C after the loss and convinced authorities at the Post Office “to suppress the distribution of the April issue through the mails. It did not seem to matter that Mencken had already been acquitted in Boston. Instead, bowing to the Watch & Ward Society, the full force of the United States government came down upon Mencken. The American Mercury was federally banned across the country. Elated, Reverend Chase gloated to reporters, “I knew I was right.”

Mencken went to the postmaster general to make his case, predictably finding the man to be the perfect model of a mid-level bureaucrat: “vain, cocksure, and unintelligent.” The ban, with its suggestion that the American Mercury was a ‘smutty’ magazine, increased sales around the country. Rodgers writes that “a new class of bootleggers sold copies of the April issue for as much as sixty dollars; others made money by selling the article itself. Too late, horrified librarians discovered the offending story about the prostitute ‘Hatrack’ had been ripped from their only copies; they began locking the magazine away. Newsdealers’ stocks quickly depleted, though not an hour seemed to pass without their being asked for it. One man chained his only edition to his stand, charging customers ten cents a read; he made more than fifty dollars.”

As for the Christian fundamentalists of the day, Rodgers notes that they felt that a victory had been won: “Entire communities seemed to agree with the Christian Index that either parents must provide something wholesome for their reading tables or be faced with the alternative of allowing ‘Mencken to provide our children with the poison which will eat out their hearts and drag their souls down to hell.'”

According to Rodgers, the end of the moral majority’s triumph came after a few weeks, with a powerful blow against the Watch & Ward Society: “A New York judge, Julian Mack, granted an injunction against the U.S. postmaster. After reading the article in the American Mercury, he said: ‘No one but a moron could be affected by it’ … sensing defeat, the government shifted its attack from ‘Hatrack’ to an obscure advertisement in the magazine. Clearly, the Puritans had lost and they knew it. Mencken failed to collect damages, but he handed the Watch & Ward Society a major setback. Many Bostonians were indignant over the bad publicity the case had given the town; many withdrew their support from the society … Now that the U.S. Post Office had been defeated, the influence that the secretary of the Watch & Ward Society has so long wielded was collapsing. Discredited and shunned, J. Franklin Chase resigned.”

Rodgers includes this April 1926 huzzah for Mencken and his battle for free speech from a London Sunday Express reporter: “Mr. Mencken nearly always makes me angry when I read him, which I am sure is the only effect he would wish to have on me, but I always have to admit that here is a man who deserves well of his age, because he is against humbug when humbug is terribly successful on two sides of the Atlantic.”

Thus this date should be celebrated — if only because humbug never sleeps.

Tagged: American Mercury, Banned in Boston, H. L. Mencken, censorship, free speech