Fuse Theater Review: O Superannuated Man

In DELUSION, veteran performance artist Laurie Anderson generates a muted melancholy, sometimes poetic, sometimes poignant, that makes the piece a consistently compelling if not always successful addition to an ambitious body of work.

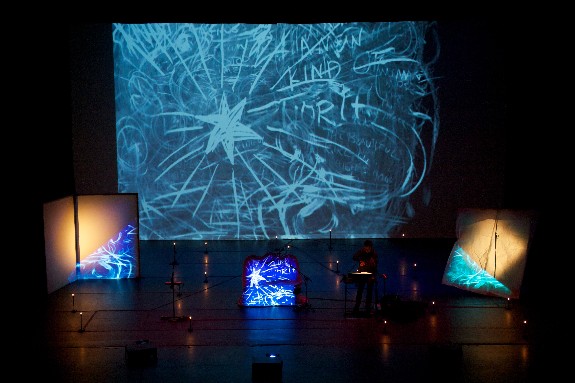

Laurie Anderson performing DELUSION at Campbell Hall, UCSB Photo credit: Lawrence K. Ho Los Angeles Times

Delusion. Written and performed by Laurie Anderson. Presented by Arts Emerson the Paramount Center Mainstage, Boston, MA, through October 2.

By Bill Marx.

It has been 30 years since Laurie Anderson became a brand-name performance artist with the song hit “O Superman” and at the age of 64, she has decided to look back, not so much with anger, though there is some of that in Delusion, but with a muted melancholy, sometimes poetic, sometimes poignant, that makes the piece a consistently compelling if not always successful addition to an ambitious body of work.

Time, once springy in her dadesque tales and rhythmically pounding music, has taken on a distinctly autumnal tinge. The latest show is haunted by two-ton intimations of mortality, capped by Anderson’s moving narrative about going to her mother’s death bed, a problematic search for an elusive emotional catharsis. On at least one level, Delusion is an ironic title—Anderson is writing about facing some hard realities.

One of these realities is that, as an artist, Anderson has been repeating herself. For those who have seen the performance artist often over the years ( I have), the recent shows have been somewhat off-putting because she has been depending on the same “experimental” techniques that were fresh decades ago.

Anderson’s vocals still bounce from a whispery version of her normal voice to the basso profundo (or buffo) of a persona she has named Fenway Bergamot, her violin playing remains winsome but waveringly resilient, her visuals (video, drawings, light shows) continue to reach for the hyperactive and colorful. The eye-catching sight and sound is at the service of vaguely surreal, episodic narratives—with left-wing political interludes—that don’t so much progress as swirl and curl around certain images or themes, often accented by aburdist one-liners.

One of the intriguing aspects of Delusion is that Anderson appears to be aware of the recycling and is meditating on it, wondering if there is an alternative. The initial note sounded is one of creative exhaustion: the performer tells us that donkey of her art (inspiration as beast of burden?) has dropped dead—the “old” carrot is dangling in the air without a mouth to feed. This fear (?) of being played out is multiplied through different versions of inertia—the stories not only spend a goodly amount of time in the hospital, but consider the emptiness of the lunar surface (which, she tells us, NASA wants to use as a junkyard for the plastics, chemicals, and smog poisoning our planet), and contemplate our aches and pains, including a funny riff on why people always complain about cricks in their backs but never their fronts.

Of course, the artist-on-the-ropes storyline is predictable—from this confession of having reached a dead end will evolve flickers of inspiration that will be blown into a reassuring bonfire by time the piece ends. What’s interesting about Delusion is that that kind of easy, romantic resurgence that doesn’t quite happen here.

There are dreams of rebirth, one a highly amusing send-up of motherhood involving Anderson giving birth to her dog, and rich images of nature, with Anderson and violin seeming to sail above the greenery, skimming across the land. But the overall atmosphere of the piece maintains a determined, at times almost sentimental, sadness, a touch of autobiographical nostalgia.

A visit to Iceland to ride amazing horses ends with a quirky Anderson homage to the background of her Irish-Swedish dreamer of a father; there’s an admiring portrait of a prophetic but lunatic, Russian space nut born in the 19th century, and there’s Anderson’s confrontation with the inner turmoil raised by having to face her dying mother. There is much to be admired in Anderson looking so squarely at exhaustion, though this means that the piece strikes a pensive pose that it never shakes.

All of this holds your attention, but some of her avant-garde reflexes are somewhat rusty. The visuals for Delusion are disappointing—the black and white drawings, animated palimpsests in which words and images melt and then reform into different shapes, are much beholden to the “cartoons” of the brilliant South African artist William Kentridge, who does much more with the approach in his political art. The problem is that Anderson doesn’t really make the moving pictures a vital part of the piece—they are essentially a fancy “light show,” much like the abstract designs projected on Anderson as she plays her instrument. What’s more, the music pretty much plays second fiddle to the vocals—in some of the earlier pieces there was a healthy tug of war between words and tunes, combatants of equal force slugging it out. But the monologue wins out pretty easily.

Thus Delusion feels like a transition piece for Anderson, a re-grouping—not yet filled with the new, but there’s discontent with the usual grooves. In her program notes, Anderson writes that “words and stories can create the world as well as make it disappear.” She still has a way with what could be termed a language of sardonic incredulity—her musing on the finish of the American empire and the recent hailing of the American corporation as an individual (a rebuke to Mitt Romney and the conservative cult of the company as a human being) makes its predictable ideological point with deadpan verve. But if the point is to square off creation and entropy, the latter gains the upper hand. At the end of Delusion, the donkey is still dead.