Fuse Poetry Commentary: Verse Into Verse — “Poetry” Awards Poetry a Prize

In the future, when a literary historian looks at the long-forgotten Lilly Prize and wonders what did its selection panels get right, it will be recognized that it had been sensitive and intelligent enough to realize the beauty of David Ferry’s poetry, an oeuvre which is sure to grow in stature.

By Daniel Bosch.

Poet and translator David Ferry -- It is the consistency of his practice in translating and composing that makes his work truly extraordinary.

In April, National Poetry Month, the Poetry Foundation in Chicago announced that Brookline, MA resident David Ferry had been awarded the 2011 Ruth Lilly Prize for Lifetime Achievement (and an accompanying check for $100,000). He will receive the prize at the Arts Club of Chicago on Wednesday, May 11.

Ferry is a superb artist. The roster of past Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize awardees is certainly august company (it includes Adrienne Rich, Philip Levine, Mona Van Duyn, John Ashbery, Charles Wright, Donald Hall, W. S. Merwin, Maxine Kumin, Carl Dennis, Yusef Komunyakaa, Kay Ryan, C. K. Williams, Richard Wilbur, Lucille Clifton, Gary Snyder, Fanny Howe, and Eleanor Ross Taylor), but I think that this year’s awarding will eventually be understood as one of the Lilly Prize’s great moments. I mean that, in the future, when a literary historian looks at the long-forgotten Lilly Prize and wonders what did its selection panels get right, it will be recognized to the Poetry Foundation’s credit that it had been sensitive and intelligent enough to realize the beauty of David Ferry’s poetry, an oeuvre which is sure to grow in stature.

David Ferry is a marvelous translator, more widely celebrated for his version of Gilgamesh and for his Horace and his Virgil than for his own lyrics. I think this discrepant assessment arises in part from a common misunderstanding of the complex and abiding relationship between the sibling arts, translation and poetry. It may be so that most translations of poems fail to be poems in the target language; and yes, it may follow from our experience of translation as a “lossy” art that we should proceed to consume translations of poems into not-poems as if that loss is no disaster—the best we can hope for. By such reasoning translators, who practice an “art of losing,” cannot be major artists; sure, translators make, but their making is a making do. But our observations of their logical consequences don’t always prepare us for a startling reality.

The reality to which I refer is the almost unprecedented degree to which Ferry has made poems that were written in other languages into poems in English. Ferry translates verse into verse.

Verse entails manipulation of the most basic elements of language, and thus translators of verse into verse must “write” a poem in the target language if they are to succeed. Let’s say a great Latin poem is a mosaic of tiles (the same number of tiles as phonemes, pitched at some exquisite ratio P/M of phonemes to morphemes.) To translate that poem from Latin into English, as Ferry has done so many times with such great force and power, is to create, is to create a new and beautiful mosaic—a mosaic that is faithful to tonal, linear, and image complexities of the original—though almost none of the stones it is comprised of are identical to stones in the original and though the shape of the new mosaic may be as different from the ancient one as iambic pentameter is from dactylic hexameter. By this analogy, Ferry’s translation of verse into verse—all the best translation of verse—brings new and distinct poems into the world. And the best translations of verse are new poems.

Though some greats are absent, the line of writers of verse in English who have translated verse into verse or paid deep and consistent attention to verse in languages other than English reads like poetry’s honor roll: Chaucer, Wyatt, Surrey, Johnson, Milton, Pope, Pound, Eliot, Stevens, Yeats, Graves, Lowell, Wright, and Bishop. Many of these poets were publishing translators, immersed much of the time in the structures of verse in Latin, Greek, Chinese, Spanish, French, Hebrew, German, or Akkadian.

And though it matters whose verse you translate—translating bad verse is not going to strengthen your own—any attentive translation of verse into verse is like a permanent visa for travel to poetry’s central concern: the shaping of utterance, whether physical or conceptual. For none of these poets should translation be extricated from the composition of poems printed under their own names; in some cases translation was part of their daily lives. In more recent decades, this line continues. Think of poets such as Joseph Brodsky, Robert Bly, Christopher Logue, C. K. Williams, Seamus Heaney, Anthony Hecht, W. S. Merwin, Richard Wilbur, Richard Howard, Marilyn Hacker, John Ashbery, Charles Simic, Derek Walcott, Rika Lesser, Robert Pinsky, and Vikram Seth, whose work in English has been infused with energy and deepened via the practice of translation.

This long line of verse into verse translators—to which Ferry belongs—is the line of poetry itself. And that line makes a strong case that translation has never been secondary to the practice of poetry, no matter how consistently audiences fall for and break up with that chimera “originality.” In light of this line, in light of the line of verse, Pound’s dictum “Make it new” doesn’t mean “Make poems independently of the past.” It means make “it”—verse—new again.

In a brief announcement that Ferry had won the Lilly Prize, Poetry Magazine editor Christian Wiman praised the “muted and subterranean” effects in Ferry’s work and contrasted these with the “intense surface energy” on which much current poetry relies. Wiman’s term “muted” is curious but apt. What does it mean to produce words that are “muted”? Verse’s effects are produced by words made into lines, and words read in verse cannot be completely silenced; yet in any good verse, they will be altered because they occur in linear structures. By emphasizing the “muted” in Ferry, Wiman misses the volume Ferry’s verse practices can raise from ordinary words.

But Wiman also praises what he calls the “cumulative” and “seismic” effects of Ferry’s verse, and I think you can hear and feel what he meant in the following poem, an example of how when Ferry translates he makes new poems from poems by other poets, in this case by Rilke. Here is the “Song of the Drunkard”:

I don’t know what it was I wanted to hold onto,

I kept losing it and I didn’t know what it was

Except that I wanted to hold onto it. The drink kept it in,

So at least for awhile it felt as if I had it,

Whatever it was. But it was the drink that had it

And held it and had hold of me too. Asshole.Now I’m a card in the drink’s hand while he keeps smiling

Like he doesn’t give a shit in a game that’s going badly,

And when death wins he’ll scratch his scabby neck

With the greasy card and throw me down on the table

And then I’ll just be another one of the cards

In the pile on the fucking table. So what the fuck.

Nearly all of the effects Ferry achieves here follow from his employment of a strong but not rigid measure. Each of the six distinct, syntactical units he draws across its structure sound the first stanza’s theme—holding, keeping, losing—with careful end-of-line marking and medial repetitions that tighten the poem’s fabric—“I didn’t,” “I didn’t know,” “hold onto,” “had it,” “had it,” “had hold.” Ferry’s use of a juicy English expletive at the end of each stanza, such that Rilke’s German is transformed and invigorated, is surprising and delightful. The second stanza’s long sentence followed by the clipped “So what the fuck,” creates a genuine character. Ferry’s “Song of the Drunkard” is not Rilke’s poem (it’s English), but it is a splendid poem and in terms of verse it is as good as Rilke’s.

Most contemporary readers of poetry—even poets, and especially those poets who don’t translate verse into verse—won’t necessarily find it easy to tune into the technical mastery of Ferry’s lines and line-breaks and strategic repetitions, but there’s strong remedy for that in just saying his lines aloud, over and over. The poem below, an ekphrastic poem about a photograph (seen through the lens of a boldly anachronistic, classical allusion) makes savvy use of the repetition of a strong iambic pentameter line, the kind of line that one who had immersed himself too much in the concerns of today’s heroes might be afraid to use:

Plate 134. By Eakins. “A cowboy in the West.

An unidentified man at the Badger County Ranch.”

His hat, his gun, his gloves, his chair, his placeIn the sun. He sits with his feet in a dried-up pool

Of sunlight, His face is the face of a hero

Who has read nothing at all about heroes.He is without splendor, utterly without

The amazement of self that glorifies Achilles

The sunlike, the killer. He is without mercyAs he is without the imagination that he is

Without mercy. There is nothing to the East of him

Except the camera, which is almost entirely withoutUnderstanding of what it sees in him,

His hat, his gun, his gloves, his homely and

Heartbreaking canteen, empty on the ground.

Ferry’s iambic line is flexible and resilient. If he throws down a line of pure iambs (“His hat, his gun, his gloves, his chair, his place”), then he alters that line when it almost recurs; the strength of a measure, for Ferry, as for all masters of verse, is in its controlled disruption. He exploits this practice below, as he uses iambic pentameter to convey one of the most dramatic and moving scenes in classical literature, the boxing at the games held to honor the dead Anchises, in Book V of the Aeneid. Feel the blood engorged musculature of this eleven-and-a-half-line passage, packed with four sentences—two long, two short, two right crosses, two jabs—and an ecstatic energy that will burst, at the end of the scene, the skull of the ox that Aeneas has promised to the victor:

Then father Aeneas, Anchises’s son, brought out

Two pairs of boxing gloves that weighed the same

And bound their hands so they were armed the same;

Each stood, undaunted, raising up undaunted

Challenging hands to the sky, heads high and back.

And fist against fist, the fight begins, the younger

Quicker, more agile, cleverer on his feet,

The other massive in his powerful bulk,

Yet moving slowly on unsteady legs,

Knees wobbling, and his huge frame painfully

Gasping and shaking. Many blows get missed.

But many don’t.

“But many don’t,” after the pounding repetitions that preceded it, is a profound understatement. Ferry keeps his head down (like a good boxer), and his guard up: he’s watching the line—his line, not Virgil’s, which was Latin and hexametric—and he’s attending to pattern and sound, trusting that the honest work of making will lead him toward truth.

Here is Keats’ conjoining of the aesthetical and the ethical. For translators of verse into verse—Ferry is perhaps our greatest living example—the work is not merely technical; such translators get closer to the heartbeat and breath of the human being from whose imagination the great poem sprang than any other readers.

Attending to the task of translating great lines of verse—the line is the ground on which poets of every time and every culture meet—a poet can in some way participate in both the beauty and truth that those verses are the purpose-built container for. In Ferry’s depiction of Virgil’s depiction of Entellus’s incredible victory over a strapping, younger, prideful Dares, consecrated by a final, awesome blow to the forelock of an ox, Ferry too negotiates a specific emotional and ethical terrain (one I think I can translate: what do you do about beefy dumb upstarts who know nothing of pugilism—or verse).

As he manipulates lines of English verse to translate Virgil’s manipulations of lines of Latin, Ferry manipulates Virgil’s dramatic conflation of the muscular and the mental, the audacious and the angry, the self-involved and the self-conscious. The aging hulk Entellus gives a speech about how for years he bound his fists in the weighted, brain-stained gloves of his hero and mentor in fighting, Eryx, and how, today, in fighting Dares, he will abjure those bloody mitts, and its as if he’s talking about how a poet learns from past masters how to bind the lines of his stanzas, and now he must cast the old measures aside for newer, less dangerous ones.

Virgil responds to the highest needs of his culture in his construction of this scene; it gives us both excruciating pleasure and terrible sadness. Translating verse by poets as strong as Virgil and Horace and Holderlin and Rilke and Guillen has given Ferry the ability to construct poems by Ferry that respond to our needs in many of the same ways. It is the consistency of his practice in translating and composing that makes Ferry’s work truly extraordinary.

When I remind myself that the Ruth Lilly Prize is for Lifetime Achievement, I’m tickled by the surprise the Poetry Foundation has coming, as Ferry’s next book, Bewilderment, due out from University of Chicago Press in 2012, is the work of his lifetime. If translation is indeed inherently lossy, an arc of loss and grieving runs through Ferry’s work, from his poems about the loss of his mother, to his unstoppably rhythmic Gilgamesh, through his volumes of Horace and Virgil into the Aeneid. For anyone born in 1924, the arc of losses is nearly continual.

Now it has yielded, magnificently, painfully, Ferry’s most beautiful poems, torn from him since the death of his wife, the critic Anne Ferry. “Ancestral Lines,” a lyric that will appear in Bewilderment, is not Ferry’s only ars poetica. But it inscribes, with humor and grace, something important about the man who, following others’ lines, has discovered who he is. Ferry knows that to be an artist one must follow—and that even when one does, one is easily lost:

Ancestral Lines

It’s as when following the others’ lines,

Which are the tracks of somebody gone before,

Leaving me mischievous clues, telling me who

They were and who it was they weren’t,

And who it is I am because of them,

Or, just for the moment, reading them, I am,

Although the next moment I’m back in myself, and lost.

My father at the piano saying to me,

“Listen to this, he called the piece Warum?”

And the nearest my father could come to saying what

He made of that was lamely to say he didn’t,

Schumann didn’t, my father didn’t, know why.

“What’s in a dog’s heart”? I once asked in a poem,

And Christopher Ricks when he read it said, “Search me.”

Of course he wasn’t just being funny, but right.

You can’t tell anything much about who you are

By exercising on the Romantic bars.

What are the wild waves saying? I don’t know.

And Shelley didn’t know, and knew he didn’t.

In his great poem, “Ode to the West Wind.” he

Said that the leaves of his pages were blowing away,

Dead leaves, like ghosts from an enchanter fleeing.

Tagged: American poetry, David Ferry, Poetry, Poetry Foundation, Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize

Splendid post!

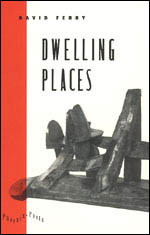

That skeleton book jacket is amazing. And in this case, apparently, the book can rightfully be judged by its cover.

right, shelley! except that the book is meatier, more muscular, and gutsier than that mosaic!