Film Review: “The Last White Knight” — A Vision of Racism Perpetuated

In the mesmerizing “The Last White Knight,” documentary filmmaker Paul Saltzman chronicles a five-year dialogue with the man who assaulted him during the civil rights movement.

The Last White Knight, directed by Paul Saltzman. Part of the Boston Jewish Film Festival at the Coolidge Corner Theater, Brookline, MA, on Sunday November 10 at 2:30 p.m.

By Tim Jackson

On August 1, 1975, Byron de la Beckwith was convicted of conspiracy to commit murder in the assassination of Medgar Evers on June 12, 1963.

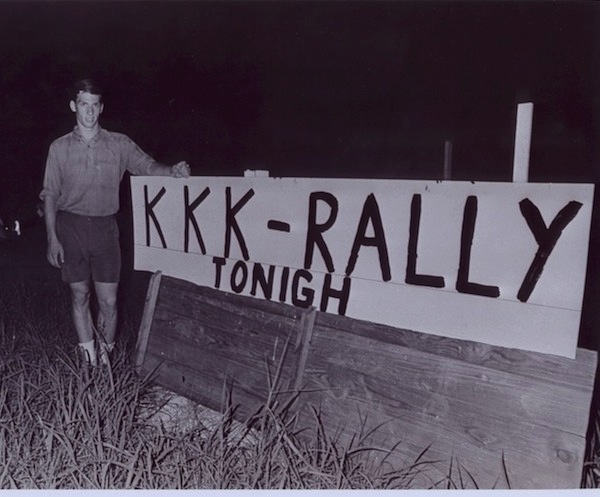

In 1961, 21-year-old Paul Saltzman was headed to the courthouse in Greenwood, Mississippi, as part of a campaign to help register black voters for the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee. He was punched in the face by de la Beckwith’s son, Delay De La Beckwith. He ran for his life.

Now a documentary filmmaker, Saltzman chronicles a five-year dialogue with the man who assaulted him in the mesmerizing The Last White Knight. The racism still alive in the hearts of de la Beckwith and his ilk stands in stark contrast to conventional notions of progress and the spread of enlightened understanding. Saltzman lets his subject freely express himself, asking him the kinds of questions that are rarely put to men of such irredeemable prejudice. It is sobering to hear de la Beckwith speak his mind, his Southern charm and presumed friendship at the service of expressing opinions so loathsome they seem to come from another age altogether.

The director also places the civil rights movement into perspective, reviewing its history by way of the voices of such accomplished black activists as Harry Belafonte, Morgan Freeman, and other lesser known participants. The deeply embedded racism and anti-Semitic convictions of the old South were very real dangers to these workers. The White Knights of the Klan particularly abhorred the liberal celebrities. The possible complicity of the FBI in the violence is even hinted at. In a jaw-dropping moment, one Southern lawyer defends the murder of Medgar Evers by calling it a kind of advocacy: “Self-defense is defense of the American way of life. The highest patriotism, the Bible says, is one who lays down his life for his friends. . . . I think it’s safe to say, we want an all American America. We want the un-Americans out. The people who can’t become part.” And de la Beckwith: “I have not changed my attitude, my views, or my thinking one bit. It’s still the same way it was in 1965.” But hang on for the movie’s conclusion.

Beyond airing shockingly backward, deeply embedded attitudes about racial superiority, The Last White Knight raises the possibility of progress and presents intimations of reconciliation. Throughout, Saltzman remains even-handed no matter how disgusting the bigotry on display; the waves of anger at what we are hearing eventually give way to frustration, then resignation, and finally a bittersweet and disconcerting sadness that comes with the realization that ignorance is still being profoundly nurtured in family, religion, and Southern history. We are still generations from acting on a basic tenet of American life—that all men are created equal.

The Last White Knight is screening as part of the Boston Jewish Film Festival

Tim Jackson is an assistant professor at the New England Institute of Art in the Digital Film and Video Department. His music career in Boston began in the 1970s and includes some 20 groups, many recordings, national and international tours, and contributions to film soundtracks. He studied theater and English as an undergraduate and has also has worked helter skelter as an actor and member of SAG and AFTRA since the 1980s. He has directed two documentaries: Chaos and Order: Making American Theater about the American Repertory Theater, and Radical Jesters, which profiles the practices of 11 interventionist artists and agit-prop performance groups. He is currently finishing a third documentary, When Things Go Wrong, about the Boston singer/songwriter Robin Lane, with whom he has worked for 30 years. You can read more of his work on his blog.

Tagged: Boston Jewish Film Festival, civil rights, documentary, Paul Saltzman

On August 1, 1975, Byron de la Beckwith was convicted of conspiracy to commit murder – but not the murder of Medgar Evers. In 1975 he was convicted of conspiracy to commit murder of a man named Adolph Botnick. He served 3 years in prison before being paroled in January 1980. He wasnt convicted of the first-degree murder of Medgar Evers until February 5, 1994 and died in January of 2001.