Fuse Commentary: MBTA Set to Demolish the “Center of the Universe” in Harvard Square

Apparently, an agency like the MBTA can simply take a wrecking ball to pieces of public art such as “Omphalos” when their existence becomes an encumbrance. No questions asked.

By Romolo Del Deo.

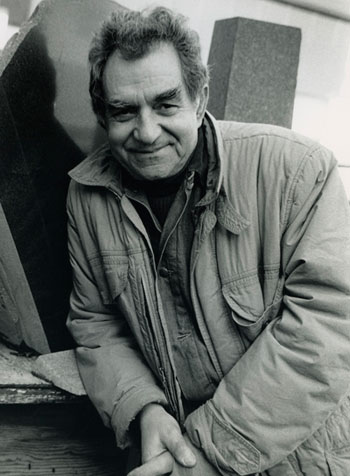

Artist Dimitri Hadzi — his well-known sculpture in Harvard Square, Omphalos, is slated for destruction.

Ironically, as the city of Boston recovers from the tragedy of the Marathon Bombing and contemplates erecting a memorial to that horrible event, another monument that has stood in greater Boston since the mid ’80s is on the verge of being destroyed: Omphalos, a 21-foot-high, granite construction situated at the juncture of Mass Ave and Brattle St. in Harvard Square.

The statue’s history is unique: in the late ’70s the Metropolitan Boston Transit Authority (MBTA), commissioned internationally renowned sculptor Dimitri Hadzi to create a monumental artwork for its Harvard Square station. The commission was part of a larger program run by the MBTA (called “Art on the Line”) dedicated to bringing art to public spaces. Hadzi was allotted $37,000, but the artist’s ambition for the sculpture demanded considerably more resources. Ultimately, major funding had to be sought from outside donors to complete the piece. The final cost for the project was close to half a million dollars.

At the time, Hadzi was a tenured professor at Harvard University, and I was his studio assistant. It was my job to enlarge from his wax maquettes a half scale version of the sculpture that was named “Omphalos,” the Greek term for “Center of the Universe.”

The project consumed Hadzi more than any other large project we worked on during the six years I was under his wing. After several years of his extended design, the actual sculpture was executed in joined granite slabs and erected at the nexus of Harvard Square. Granted, granite was probably not the best material choice for a piece in such a heavily trafficked site. Omphalos was subject to constant jarring vibrations from the endless traffic above ground and the subway below. But Hadzi had an artistic vision, and he entrusted it to the army of engineers that the MBTA appointed to oversee the superstructure.

Omphalos was unveiled in 1986, and the placement of such a monumental artwork in the streets of Cambridge was applauded, especially because of the scarcity of other public artworks in the area. The piece cemented Hadzi’s stature as greater Boston’s most publicly visible sculptor since Daniel Chester French.

Thirty years later, this red granite monument has become a fixture in the gentrified landscape of the remodeled Harvard Square, but time and endless vibrations have taken their toll.

In 2011, a small chunk of granite detached from the sculpture. The sky then fell on the “Center of the Universe.” No one was hurt, but the MBTA soon discovered several “deficiencies” in the sculpture. Reeling under the paralyzing weight of the $5.2 billion debt from the “Big Dig,” the MBTA deemed Omphalos too expensive to restore. The solution? Tear it down.

Upon hearing the news, Hadzi’s widow, Cynthia, called me, devastated that one of her husband’s major works would be destroyed. She was determined to find donors to fund the half million dollars that the MBTA engineers estimated would be needed to save the monument. But she fell far short of her goal.

Nor did any public arts organization charged with protecting greater Boston’s artistic legacy (such as the Mass Council for the Arts, the Museum of Fine Arts, MassMoca, Cambridge Arts Council, and the Boston Art Commission), offer to try to save the monument or partner with the MBTA to find an alternative to destroying it.

The local press has also been silent: as I write this, not one story has been published about the situation since it unfolded in early summer. The sculpture is now set to be demolished in early September, before Harvard students return for the fall semester.

Ironically, in 1998, Hadzi gave an interview with the Boston Globe where he suggested, prophetically, that Boston did not hold him and his work in the same high regard as other cities.

With less than 30 days left before Omphalos meets its demise, it is puzzling that a city known for its healthy cultural dialogue and a vibrant press is going to let the MBTA demolish public property and legacy artwork (which was donated to the city) without a cry of protest or concern, even for making more responsible use of taxpayer dollars.

Even more embarrassing, where is Harvard University in all this? The school has decided to punt on protecting an important artwork by one of its celebrated own. It has been surprisingly silent, uttering not a word on the matter nor working behind the scenes to try to stop the destruction.

In Boston, as in other cities like New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and the District of Columbia, the public entrusts tax revenues and donations to transportation authorities like the MBTA to acquire art that enriches public spaces. Apparently, despite all of the initial PR hoopla, these acquisitions are only seen as decoration, not valued as artwork that is an important part of a community’s legacy. An agency like the MBTA can simply take a wrecking ball to pieces of public art when their existence becomes an encumbrance. No questions asked.

Given this absurd state of affairs, how do we attract significant artists to create great public works if they suspect that we will raze them into rubble the moment their preservation becomes inconvenient? Equally important, how do we ask donors to make generous contributions to art in the public trust if their gifts have a shelf life of a few decades? And this raises a larger and even more distressing question: How can a country that doesn’t protect and cherish its cultural artifacts leave a lasting legacy of value? The precedent being established here, what it says about a greater malaise of cultural indifference, is huge: the implications for Boston, for public art and its future, are serious and national.

The MBTA’s intention to destroy a public treasure should be a wake up call to all those who love art, not only in Boston, but in any city whose artworks are under the care of bureaucratic, bean-counting agencies without artistic expertise or respect for cultural heritage. When the “Center of the Universe” can be junked, is anything else safe?

Romolo Del Deo is a sculptor using ancient methods and visual tropes to convey contemporary meaning. With extensive training in Italy and the US (including at Harvard as Dimitri Hadzi’s studio assistant), he pushes archaic casting techniques to create unique, poetic, glassine bronze castings. Del Deo’s work is in numerous public collections and museums. After three decades in NYC, Del Deo recently moved to Provincetown, MA where he is currently creating a large monumental sculpture for the town. Locally he is represented by Berta Walker Gallery and LaMontagne Gallery.

Tagged: Art for the Line, Dimitri Hadzi, Harvard Square, MBTA, Omphalos, public art, Romolo Del Deo

Following up on the story The Arts Fuse broke last night about the destruction of “Omphalos,” Geoff Edgers has finally had his piece on the fate of this sculpture see print as a featured story in the Boston Globe‘s G Magazine. I am glad that the Globe is finally giving this story the attention it deserves, though Geoff’s well-researched article, while correct, misses a few salient points about the bigger story the situation raises, which is not just the bungling of the salvage of one sculpture in Boston. It is the bigger story of how such issues are handled here. There are many cities in the world who protect and preserve their public art, many of them with far more meager resources than greater Boston and Harvard University. We zone and legislate to protect important historic architecture, but we stand by, our hands in our pockets, when art’s existence is on the line. This has to change, as does the culture of complacency.

In a related story, not covered in the Globe article but being made public now in The Arts Fuse, I have also discovered that the giant marble waterfall fountain sculpture in Copley Place, also by Hadzi, is going to be demolished because the six shops behind it say they aren’t getting enough visibility. Of course, the sculpture was in place before their respective leases were signed (and it is hard not to speculate that their gripes about visibility may have something to do with negotiating rent relief). This sculpture is the largest stone sculpture in New England and a major backdrop for many who meet in Copley Place or use it as a backdrop for nuptials, etc…A shopkeeper I spoke with — whose store strategically fronts this sculpture — said it is a major draw, a cultural icon for the indoor shopping center. But, like “Omphalos,” it too is slated for destruction without the benefit of a public hearing that could provide possibilities for its rescue.

Granted, this sculpture is on private land, but how does the destruction of this sculpture differ from say, a decision of the Vatican to remove Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel Ceiling because it doesn’t suit current church use? Is the right to destroy public art absolute? Does no one see the tragic folly in Boston’s apparent willingness to remedy its public art problems with dynamite and wrecking balls? To me, these cases suggest the powerful need to consider the creation of an effective, coordinated, and enlightened pan-urban arts council that deals with issues of public art and zoning. We must carefully evaluate how we sit in judgement of public art, how we weigh its value. If Boston would demolish, rather than fight to preserve, our future legacy, then how can we encourage artists to create public art, and enlightened donors to give?