Culture Vulture: Reading Jung’s “Red Book,” Part Two

The “Red Book” was Jung’s attempt to understand himself as well as the structure of the human personality in general and the relation of the individual to society and the community of the dead.

THE RED BOOK by C.G. Jung. Edited by Sonu Shamdasani. English translation by Shamdasani, Mark Kyburz, and John Peck. W.W. Norton & Co. 404 pages, $195.

By Helen Epstein

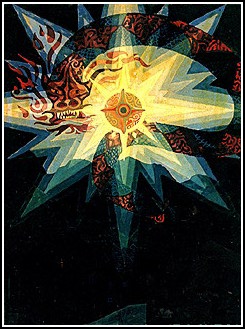

The Light at the Core of the Darkness in C.G. Jung's Red Book

In 1900, at 25, Jung was an assistant staff physician and psychiatric trainee of Dr. Eugen Bleuler, working with severely disturbed patients at the Burghölzli, the world-famous insane asylum and university clinic of Zurich. His medical dissertation “On the Psychology and Pathology of so-called Occult Phenomena,“ inspired by the research of French-Swiss psychologist Theodore Flournoy, was accepted a year later.

The volume’s editor, Sonu Shamdasani, does not give us a sense of what Jung was like at the time but his biographers, Ronald Hayman and Deirdre Bair both portray him as a tall, blond, loud, self-confident figure, who aroused strong competitive feelings among his peers, partly because of his blunt and out-sized personality, partly because he was a favorite of Burghölzli’s director Eugen Bleuler.

Bleuler took a special interest in Jung’s research in word association, long, rigorously controlled experiments demonstrating the role of the unconscious that some regard as his most important contribution to psychoanalysis.

Pierre Janet, one of Jung's intellectual mentors.

Bleuler and Flournoy both initially served as Jung’s intellectual mentors yet, in 1902, Jung chose to study with a third, Pierre Janet, in Paris. In addition to attending Janet’s lectures and working in his laboratory, Jung explored the city, especially its vast collections of Near Eastern and European art, sometimes copying what he saw in oils and watercolors. He also spent two months in London, where he perfected his English and first saw Aztec and Inca art.

When he returned to Zurich in 1903, he married Emma Rauschenbach and took a higher-ranking position at the Burghölzli. His wife belonged to one of the richest families in Switzerland. Her money would later enable Jung to build a large house on Lake Zurich, leave Burghölzli (where he disliked his administrative duties) and establish a private practice.

He was a very successful young psychiatrist — distinguished lecturer in psychiatry at the University of Zurich, busy consultant and senior staff physician at the Burghölzli — when Jung, early in 1906, initiated a correspondence with Sigmund Freud. Freud was about to turn 50 and although internationally famous, unacknowledged in academic circles; Jung was 19 years younger, a rising star at the University of Zurich.

He sent Freud a copy of his book “Diagnostic Association Studies,” research that confirmed Freud’s theories about the mechanisms of repression and included a chapter that drew extensively on one of Freud’s published cases. A year later, Jung traveled to Vienna with his wife and a young protégé of his own who recorded that Freud named Jung his “scientific son and heir.”

After Jung arrived at Freud’s home for lunch on March 3, 1907, the two went into Freud’s consulting room and talked until one o’clock in the morning. During that first long meeting Freud became convinced that Jung was his great white hope for psychoanalysis. While Freud was Austrian, Jewish, and worked outside the academy, Jung was Swiss, Christian, and on the medical faculty at the University of Zurich.

He had just completed a new book on schizophrenia, “The Psychology of Dementia Praecox,” that would attract even more world attention to the already prestigious Burghölzli. Jung was in Freud’s assessment the psychiatrist who could bring the Swiss into the Freudian fold and transform the largely Viennese-Jewish society into an international movement.

C.G. Jung

Apart from organizing his colleagues back in Zurich, Freud also wanted Jung to organize and edit an international journal dedicated to psychoanalysis. Jung biographer Dierdre Bair notes that Jung fell into intense and instant intimacy with Freud. In a letter to him six months later, Jung compared his “veneration” of the older man to a “religious crush,” and, in a peculiar foreshadowing of the future of their relationship, revealed that he had once been sexually victimized by a man he had “worshiped” and since then had difficulty with any man who tried to become a close friend.

Jung returned to Switzerland committed to Freud and stayed committed for six years. But he had many other things on his mind during those years. At the time, he was, after Eugen Bleuler, second in command at Burghölzli, charged with what he found onerous administrative tasks, and the more interesting but very time-consuming supervision of new physicians at the hospital and new medical students at the university.

He had his own patients. He lectured extensively. He welcomed international visitors. He testified in court cases. He had purchased a piece of land and was supervising the building of a large house. His wife was pregnant with their third child and insisted he spend “family time” with them.

Jung’s response to the pressure was to succumb to flu for much of the year. He was frustrated to have no time for his own research and irritated by the politics at Burghölzli, where other doctors felt he was not doing his job. Despite all of that, he organized a Swiss society for Freudian Researches and investigated the means of publishing The Jahrbuch, a psychoanalytic journal that Freud desired.

Shamdasani in his introduction to the “Red Book” downplays the role Freud played in Jung’s life and spiritual crisis. Jung’s relationship with Freud has been “much mythologized,” he argues, and a “Freudocentric legend” established that has led to “the complete mislocation” of Jung’s work “in the intellectual history of the twentieth century.” To fill in the blanks, I turned back to Deirdre Bair’s biography.

In her account, Freud pursued the younger man by mail, urging him to convert his boss, Dr. Bleuler, as well as the rest of Swiss psychologists to his cause. Jung was an erratic correspondent, too preoccupied by his many duties and interests to write back right away.

In September 1908, Freud made a visit to assess Jung’s progress. The two men again talked non-stop for four days in another operatic episode of intense intimacy after distance. Freud observed some of Jung’s patients at the Burghölzli (but did not even stop in to say hello to its director). The two men were totally absorbed in one another, thrashing out editorial details of the upcoming “Jahrbuch” and discussing the psychoanalytic movement.

After Freud left, Jung had an unpleasant surprise. Bleuler fired him. Since Zurich was a small place, both men were interested in saving face and since Jung and his family were still living on the asylum grounds as was the custom in Zurich, and his new house on Lake Zurich was still in the process of being built, Jung negotiated a deal that allowed him to formally resign the following spring.

As Shamdasani spins it, “In 1909, Jung resigned from the Burghölzli to devote himself to his growing practice and his research interests …that shifted to mythology, folklore and religion…these researches culminated in ‘Transformations and Symbols of the Libido.’” In its pages, Jung would publicly part ways with Freud by denying the primacy of sex in Freud’s theory of libido, and taking issue not only with his interpretation of dreams and the importance of religion, but with Freud’s views on the centrality of infantile sexuality.

Bair writes that Jung was so terrified by the probable consequences of writing the second part of his book that he began to practice yoga to gain the courage necessary even to approach it. In a letter to Freud in 1912, he described “grisly fights with the hydra of mythological fantasy” but did not go into specifics. “Years later he tried to describe what happened,” Bair writes, “but even with distance and time he could not express it in a logical and coherent manner.”

Samdasani’s introduction suffers from some of the same incoherence, possibly because he so wants to avoid a “Freudocentric” approach, possibly because it’s difficult to write coherently about so multifarious a life and seemingly incoherent a body of work. He skips over the deepening of Freud and Jung’s intense and fascinating relationship, omitting not only their increasingly lop-sided correspondence but their intense month-long voyage in each other’s company to the U.S.

In 1909, they set sail from Bremen to be awarded honorary degrees at Clark University, in Worcester, Massachusetts. G. Stanley Hall, Clark University’s president and himself a psychologist, had invited both of them. Freud’s five lectures were titled “The Origin and Development of Psychoanalysis” and Jung’s three lectures “The Association Method.”

Freud later wrote: “In Europe I felt as though I were despised; but over there I found myself received by the foremost men as an equal. As I stepped onto the platform at Worcester to deliver my “Five Lectures upon Psychoanalysis” it seemed like the realization of some incredible day-dream: psychoanalysis was no longer a product of delusion, it had become a valuable part of reality.”

Freudians have written Jung so well out of their history that many people don’t know that Jung was even present at Clark University. In fact, the two men spent four weeks in each other’s company almost every day, arguing, analyzing, sightseeing, accompanied by Sandor Ferenczi, who had studied with both. Jung was an enthusiastic tourist, hiking with his hosts as well as discussing parapsychology, religion and spiritualism with experts like William James and comparing him and other older psychologists favorably to Freud. But during that month, Jung, by all accounts, kept his growing reservations about Freud to and perhaps from himself.

In addition to their differences about the interpretation of dreams, the centrality of infantile and childhood sexuality; and the importance of spirituality, the two men were the products of very different families, intellectual and cultural traditions, and cities. They also had very different personal agendas. Ebullient Jung had wide-ranging interests and a very active family and extra-marital life. Austere Freud was more narrowly focused on psychoanalysis and saw Jung as a proselytizing agent for it.

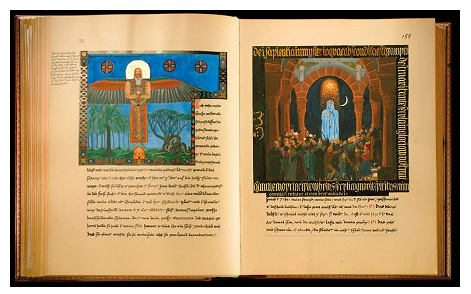

Pages from C.G. Jung's Red Book

Jung had put together the first edition of the “Jahrbuch” to Freud’s satisfaction and the older man planned to install him as first President of the International Psychoanalytic Association in 1910. But Jung had many other things on his mind (including ongoing problems with patients, colleagues and several women including his wife) and his experiences in the U.S. had complicated his relationship with Freud.

As Shamdasani narrates it, Jung returned to his cultural and religious preoccupations after the trip to America and, in addition to growing his private practice, published –- despite his trepidations –“Transformations and Symbols of the Libido.” The book was based on fantasies of an American woman named Frank Miller who had originally presented them to Theodore Flournoy, who had translated them into French but then gave them to Jung.

Shrinks had a very casual code of behavior regarding patient confidentiality, boundary violations, and many other things during those pioneer days. Jung compared Ms. Miller’s fantasies to images in comparative mythology, religion, and folklore. He differentiated between verbal, scientific, and logical “directed thinking” and passive, imagistic, and mythological “fantasy thinking.” He later viewed this book as “marking his discovery of the collective unconscious,” but he scrawled at the end of the manuscript: “What have you written, what is this now?”

That summer of 1912, he wrote “Nine Lectures,” which he would present in New York City that fall. The document would answer his own question and further demarcate his own ideas from Freud’s.

That period can, in retrospect, be seen as marking the genesis of the “Red Book” although, as Deirdre Bair points out, Jung recycled the narrative so many times that it’s very hard to determine what happened when. The theoretical rifts between the psychoanalysts of the International Association took on the character of religious wars: brutal, uncompromising, and vituperative. Shamdasani’s introduction implies that Jung’s “Most Difficult Experiment” began with a dream he recorded in “Black Book #2” in 1912 that implicitly challenged Freud.

“I was in a southern town…an old Austrian customs guard or someone similar passes by me…Someone says ‘that is one who cannot die. He died already 30-40 years ago, but has not yet managed to decompose.’ I was very surprised. Here a striking figure came, a knight of powerful build, clad in yellowish armor. He looks solid and inscrutable and nothing impresses him. On his back he carries a red Maltese cross….I hold back my interpretative skills. As regards the old Austrian Freud occurred to me; as regards the knight, I myself.”

Shamdasani continues, straining credulity: “Jung found the dream oppressive and bewildering and Freud was unable to interpret it.” In the same ‘Black Book,’ half a year later, Jung describes a second dream about a beautiful white bird that flew into his family’s apartment and turned into a blond little girl, then back into a bird that flew away.” Jung had no trouble interpreting that dream right away and embarked on a life-long sexual liaison with his former patient and professional colleague Toni Wolff.

In January of 1913, Freud broke off their deteriorating correspondence, setting the acerbic international community of analysts abuzz with speculation of what would happen next. Jung maintained his affiliation with the psychoanalytic movement until October when, after an unpleasant, contentious re-election as president of the IPA, he finally resigned as editor of the “Jahrbuch.”

Then, he had the dream that he describes at the beginning of the “Red Book:”

“It happened in October of the year 1913 as I was leaving alone for a journey [he was on his way to visit his mother-in-law in Schaffhausen, where the Rhine creates a famous waterfall] that during the day I was suddenly overcome in broad daylight by a vision. I saw a terrible flood that covered all the northern and low-lying lands between the North Sea and the Alps. It reached from England up to Russia, and from the coast of the North Sea right up to the Alps. I saw yellow waves, swimming rubble, and the death of countless thousands.

The vision lasted for two hours. It confused me and made me ill. I was not able to interpret it. Two weeks passed then the vision returned more violent than before, and an inner voice spoke. ‘Look at it, it is completely real, and it will come to pass. You cannot doubt this.’ I wrestled again for two hours with this vision but it held me fast. It left me exhausted and confused. And I thought my mind had gone crazy.

“From then on the anxiety toward the terrible event that stood directly before us kept coming back. Once I also saw a sea of blood over the northern lands

“In the year 1914 in the month of June, at the beginning and end of the month, and at the beginning of July, I had the same dream three times…”

Jung retold and rewrote this dream in many different ways in subsequent years but in the “Red Book,” he seems to be using its precognitive vision of World War I to establish the prophetic nature and validity of what he called his “waking fantasies” or “active imaginations. The ensuing account of how Jung lost and found his “soul” contains the materials for all of Jung’s analytic psychology.

Shamdasani summarizes the “Red Book” as an attempt to understand himself; the structure of the human personality in general; the relation of the individual to society and the community of the dead; the psychological and historical effects of Christianity and the future religious development of the West.

He notes that in November of 1914 Jung studied Nietzsche’s “Thus Spoke Zarathustra,” which he had first encountered as a young man, and which now “shaped the structure and style of ‘Liber Novus’ (New Book)….There are also indications that he read Dante’s ‘Commedia’ at this time, which also informs the structure of the work…but where Dante could utilize an established cosmology, ‘Liber Novus’ is an attempt to shape an individual cosmology.”

Helen Epstein’s essay on “Narrative in Memoir and Psychoanalysis” appears in this winter’s issue of “Psychoanalytical Perspectives” and in the newly published “Ecrire la Vie.”

[…] Parts Two and Three of this review of Jung’s “Red Book” go to […]

to reprise jung’s fantastic — operatic (wagnerian — psycho-dramas –the german soul was boundless) — & not at least allude to the fact that carl jung initially thought of Nazism as rebirth of WOTIN in the german soul and that his followers buried his ties to the nazis is pretty shoddy work, esp. for a jew, helen.

Do you NOT think that Nazism was “a rebirth of Wotan in the German soul”?

And when you’re prepared to read all the voluminous documentation of what Jung did and didn’t do before, during and after the second world war in regard to Jews, and provide convincing documentation for your idea that he had “ties to the nazis” I’ll be happy to discuss with you whether or not my work is “shoddy.”

dear Dr. Epstein,

I found your review of the Red Book very interesting. As a Jungian analyst whose parents were also Jungian analysts and who were analyzed by Jung, I found your review fair with regards to Jung.

Thank you,

Tom Kirsch

briefly:

(from http://www.history.ac.uk/resources/e-seminars/samuels-paper)

. . . in his paper, The State of Psychotherapy Today (1934), Jung wrote:

Freud did not understand the Germanic psyche any more than did his Germanic followers. Has the formidable phenomenon of National Socialism, on which the whole world gazes with astonishment, taught them better? Where was that unparalleled tension and energy while as yet no National Socialism existed?

In the same paper. . . Jung asserted (about Jews):

“The ‘Aryan’ unconscious has a higher potential than the Jewish.” “The Jew who is something of a nomad has never yet created a cultural form of his own and as far as we can see never will, since all his instincts and talents require a more or less civilized nation to act as host for their development.” “The Jews have this peculiarity with women; being physically weaker, they have to aim at the chinks in the armour of their adversary.”

i’d be less anti-jungian if jungians were capable of being more honest about jung. jung’s lapses into antisemitism are not served by the denial; they are magnified.

as for “wotin” being responsible for nazism, well, no, actually, i don’t blame gods for human history, i blame humans.

Blume has a point that Jung sometimes strayed into both the wackily anti-Semitic and pro-Aryan stereotypes of his day – but was he really a collaborator, as Blume seems to hint? It’s my understanding that Jung criticized Hitler vehemently and worked up psychological profiles of Third Reich leaders for the Allies. What’s troubling, I think, about Epstein’s articles is her concurrence with Jung’s mystical ideas about dream states – ideas which (like Freud’s) recent scientific research has pretty much thoroughly debunked.

I should have added that Blume’s deeper point – that Jung’s mystical-collective-identity schtick easily degrades into fascist mythology – is, of course, entirely valid.

Based on what little I know about Jung’s biography, it appears his views on Naziism, antisemitism, and Jews shifted around quite a bit between 1933 and 1945. I’ll let someone more knowledgeable consider whether this shift owes more to political expediency, a genuine development in his thought, or greater political awareness.

Harvey and Thom are correct regarding the manner in which collective identity mysticism often gets swept up into fascism. Umberto Eco also notes it as one of the identifying characteristics of fascism as well.

There is also the matter of how many neo-Pagans, many of whom count Jung as either an influence or one of their own, who are generally reacting against some form of mainline Christianity, tend to scapegoat everything they find objectionable about Christianity on Judaism (whether or not it is theologically accurate.) That said, the influence of neo-Paganism on Nazi antisemitism is probably overestimated since self-identified neo-Pagans never amounted to more than 3.5% of the German population during those years.

Which leads to the more salient question: Is Jung guilty only of dressing up anti-Semitic, and pro-Nazi sympathies in his particular theoretical framework, or did these positions have a greater influence?

Thank you. A wonderful review. I have only just received my copy of the Red Book and am immediately overcome by its aesthetic beauty and am looking forward to diving into the depths of Jung’s deeply personal waking fantacies and soul journey.

With regards to his Oct. 1913 dream, you alluded to other instances in which Jung spoke of it in a different context or perhaps an alternative interpretation other than as precognitive (of WWI). Would you mind sharing a bit more about those other references or suggest some sources where he mentions that dream?

I ask because I too have had “big dreams” that seemed at once personal as well as globally/collectively signficant and perhaps precognitive. I have always understood its dual role as mutually supportive and descriptive of the internal/external experience.