Film Interview: Talking to Zach Baliva, Director of “Potentially Dangerous”

By James Pasto

Potentially Dangerous is a documentary about an era during World War II when Italians living in the United States were persecuted — and, in some cases, interned — as “enemy aliens” because the US was at war with Italy.

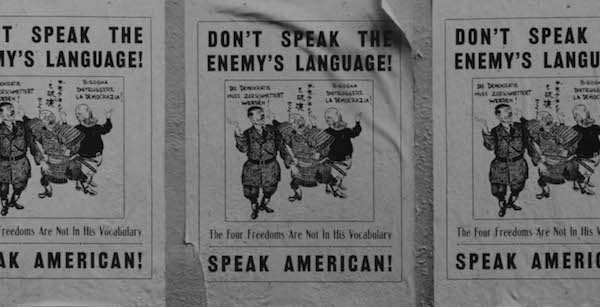

Propaganda posters from WWII.

During World War II the US Government restricted the actions and freedoms of 600,000 Italian residents of the United States. They were declared to be “enemy aliens.” Many were placed under curfew, banned from their workplaces, evacuated from their homes and communities, and even placed in internment camps. Interned Italians were not charged with a crime or allowed legal representation. They were subjected to “loyalty hearings” and held for the duration of the war. The United States government considered them “potentially dangerous” not based on anything they had done, but on where they were born. Most Italians refused to speak about what happened to them. Even 80 years later, many have remained silent.

Director/producer Zach Baliva has given them an opportunity to break their silence with his documentary Potentially Dangerous. The film can be viewed on PBS stations this month — check your cities for times. Locally, it will be screened at I AM Books, 124 Salem Street, Boston, on April 4, 6 to 8 p.m. There will be a special screening/panel discussion at Boston University’s Kilachand Hall Commons, Boston University, Room 101, on April 5, from 5 to 7 p.m.

I asked Baliva a few questions about the genesis of the documentary, the filmmaking process, and the movie’s relationship to the incarceration of Japanese Americans.

Arts Fuse: What was the genesis of this project?

Zach Baliva: Potentially Dangerous is a documentary about an era during World War II when Italians living in the United States were persecuted and, in some cases, interned, as “enemy aliens” because the US was at war with Italy. 600,000 Italians across the United States — because they hadn’t naturalized yet — were forced to go to the Post Office and register and to carry identification cards. In many cases they had to forfeit personal property. If they lived in cities near military installations they were often placed under curfew. People were evacuated and forced to leave their homes. This was a big deal, and it’s fascinating to me that there are huge portions of even the Italian-American population who are unaware that these things took place.

I got the idea for doing the film when the topic came up at a Russo Brothers Italian American Film Forum. I had spent a year living in Venice and came back to the US right when Covid-19 was first starting. I’ve worked in the film industry for many years, and I was looking for something to do as a next project and I saw the deadline to apply for the film forum was coming up. I didn’t have a topic in mind and that’s how this project really hit my radar.

I was shocked I had heard nothing about it before. We all know about the Japanese-American experience during the war, but there’s also an untold part of our history regarding what happened to Italians during that time. As I learned more I became increasingly fascinated and it turned into a passion project: this is a film about people who were impacted by these events but have never really been able to tell their story. I wanted to give them a vehicle to do that. The film was a way to bring an unknown chapter in American history to light.

AF: Can you remember the moment that you knew you had to make this film?

Baliva: Well, there were a couple of key moments. One of those was when I was doing the research and found out that Italians in New York were detained at Ellis Island as part of this process. For me, this was an important and interesting juxtaposition. Most Italian-American families have members who were processed through Ellis Island when they came over from Italy to the United States. The place is an important part of our heritage. And then to learn that not that many years later Italians were detained in the same facility under suspicion of being traitors against the very country that they had called home for many years. People that we interviewed for the documentary had family who were held there for no reason other than suspicion based on who they are and where they were born, even though in some cases they had lived in the US for decades.

Another motivation was exploring the powerful issues raised by assimilation. Remember, many Italians living in the United States still had connections to Italy, they had family there. But we were at war with their native country. When do you forget that you are Italian? Or do you?

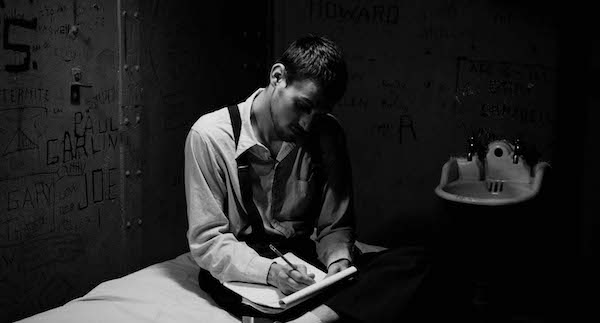

Actor Ty Ballion as interned Italian Louis Sdraulig in Potentially Dangerous.

AF: How did you research this story?

Baliva: One of the historians featured in the documentary is Lawrence W. DiStasi, who has an enormous wealth of knowledge on what happened. He’s written extensively on this topic for decades — he has led the effort to tell this specific story. He has written a couple of books: Branded: How Italian Immigrants Became ‘Enemies’ During World War II and Una Storia Segreta: The Secret History of Italian American Evacuation and Internment during World War II.

AF: Who did you get to speak to about the persecution, given that it took place over 80 years ago?

Baliva: Most of the people we spoke to were under the age of 10 when this happened. Their parents, obviously, are no longer with us, and so most of the people we interviewed are in their 80s and 90s now. Connie, for example, was a young girl when the FBI raided her home and took her father away. Velio Bronzini, who lives near Oakland, was at the dinner table when the police knocked on his door, questioned his father, and ultimately shut down his father’s business. It is time to talk to these people while they are still with us. Bronzini is somewhere around 92 years old. If we don’t tell this story now, we’re going to miss an opportunity to create an invaluable oral history.

AF: Are there any new revelations in Potentially Dangerous?

Baliva: We interviewed people who were affected by these events and found out that they had never shared their stories before. I don’t want to discount Di Stasi’s life’s work. It’s not the first time that many of these stories have been told. But, despite DiStasi’s great efforts and the work of other authors, such as Stephen Fox, and a segment in John Maggio’s PBS documentary on Italian Americans, many people are not fully aware of these events, or, if they are aware of them, most have scant idea of how and why they happened. One of the historians in our documentary, Luca Signore, says that the persecution of Italian Americans is a footnote in textbooks. If it is mentioned, it is in parentheses, after the incarceration of Japanese Americans.

AF: Was it difficult to have witnesses speak up about what happened?

Baliva: There was some reluctance. They felt a lot of shame, a lot of embarrassment about what happened. But now, for whatever reason, they’re more willing than they have been before to share the truth about what happened, what the Italian-American community went through and how it impacted it.

AF: How does the documentary go about telling the story?

Baliva: The film draws on personal testimony, archival footage, and on some beautiful recreations made by producer/cinematographer Noah Readhead. We use actors and black-and-white footage to complement the first-person testimony of the witnesses. My wife, Naomi Baliva, was our other producer, so we were a team of three. (John Turturro was executive producer.) We received a grant from the Russo Brothers Film Forum and then did a small fundraising campaign on Kickstarter to round that out. I’m really proud of what we were able to pull off together, because we did this all with a small core team of three over five months in a pandemic environment.

Bob Scudero discusses the experience of his mother, Rose, who was evacuated from her home in California in Potentially Dangerous.

AF: Were any particular cities or areas of special interest?

Baliva: We had a foundational experience at the Pittsburg Historical Museum in Pittsburg, California (that’s Pittsburg without an “h” ). It is one of the cities located near a US military installation, the main point of embarkation reserved for people leaving the West Coast. It was a sister city to a small city in Sicily. Because of that, it had a huge Italian population: the entire town was made up of Italian immigrants. But it was dwarfed by the US military encampment there. The worst started after Italians were declared “enemy aliens.” We talked to Bob Scudero, whose mother Rose was from there. Her father was an American citizen working to build ships for the Defense Department, but his wife had not yet completed the citizenship process, so mother and daughter had to leave their home, along with almost 2,000 other people from this city.

AF: Are there any aspects of the film specific to Boston that Italian Americans living here would find interesting?

Baliva: One thing worth mentioning about Italians in Boston was that we learned about the transmission of propaganda broadcasts targeting the Italian neighborhoods in the city. So there was suspicion, though at the same time the Italians on the East Coast were looked at with some favor by the government because they were a key voting bloc for Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Also, I think the government was worried about labor shortages in the shipyards if the Italians were forced to leave en masse. So the persecution of the Italians in the Boston area was more focused on individuals, such as background checks. And keep in mind, they were still part of that 600,000 nationwide who had been declared to be “enemy aliens” and placed on these lists if they hadn’t yet been naturalized.

AF: What lessons does the film have for today?

Baliva: I think it has lessons for all Americans. This is a historical documentary, but it has modern day implications when it comes to issues of war, refugees, immigration, and justice. It should spark important conversations about those topics. What values do we hold dear as a country? How do we want to treat the immigrants and refugees among us? I know that this is a story that’s often been told from the Japanese perspective. There are differences, but also powerful similarities. One is that we know that people from both groups served in the United States military during and after persecution. I think that’s an interesting aspect of this: here were two groups who were loyal to America and interested in proving their loyalty, no matter how the government acted.

James Pasto is from Boston’s North End and teaches in Boston University’s Writing Program. His area of focus includes Italian American and North End history.