Book Review: “All Sorts of Lives” — Katherine Mansfield, A Magician With Words

By Roberta Silman

We can only wonder what Katherine Mansfield might have given us had she lived a normal life span, but we should cherish what we have, as Claire Harman has done so beautifully.

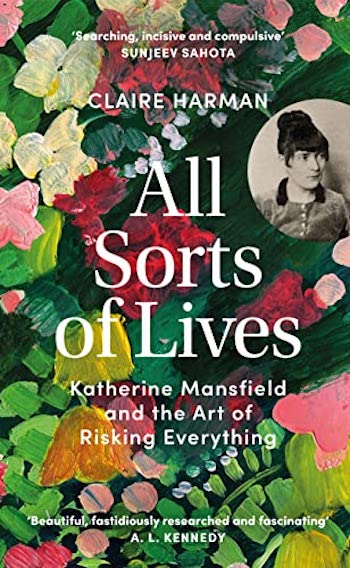

An appreciation of Katherine Mansfield including All Sorts of Lives: Katherine Mansfield and the Art of Risking Everything by Claire Harman. London. Chatto & Windus, 295 pages, £18.99.

Katherine Mansfield died a hundred years ago this winter at age 34. Although she was so young, she has a special place in the literary canon as someone who changed the course of the short story in the 20th century. As a young writer I remember reading some of her stories many times, trying to pin down how she could take the most ordinary of events — for example, moving house in “Prelude” — and create a story so vivid that I can still tell you about those children and their parents and aunt and grandmother in great detail. In those days I knew that Mansfield, New Zealand’s great treasure, was a magician with words, that she was considered a “modernist,” that her best work shimmered with an unusual tenderness, and that her characters could creep into your heart, leading to comparisons with Woolf and Joyce and T.S. Eliot.

Katherine Mansfield died a hundred years ago this winter at age 34. Although she was so young, she has a special place in the literary canon as someone who changed the course of the short story in the 20th century. As a young writer I remember reading some of her stories many times, trying to pin down how she could take the most ordinary of events — for example, moving house in “Prelude” — and create a story so vivid that I can still tell you about those children and their parents and aunt and grandmother in great detail. In those days I knew that Mansfield, New Zealand’s great treasure, was a magician with words, that she was considered a “modernist,” that her best work shimmered with an unusual tenderness, and that her characters could creep into your heart, leading to comparisons with Woolf and Joyce and T.S. Eliot.

And also that her intelligent clear-eyed observations could produce bitter, sometimes cruel and brittle tales about the venalities that characterize so much of real life. In her stories she flew from one consciousness to another, often shifting points of view: you were pulled in as you read bits of dialogue and thought so that everything seemed to be happening all at once. This appetite for spontaneity and immediacy could also lead to a frenetic, almost frantic quality in the writing. But Katherine didn’t care; she seemed to be afraid of nothing. Moreover, she was trying something new with each story. While some were less successful than others, she was clearly someone to learn from.

What I didn’t know was very much about her life. Although Katherine died in 1923, it took 30 years for the biographies to start coming. From Anthony Alpers and Jeffrey Meyers and later Claire Tomalin we learned that the price of her unique vision and often exquisite prose was a hard, short life filled with unimaginable challenges. And now, to mark the centennial of her death, Claire Harman has put together an intriguing book which examines 10 stories in chapters that begin with an exegesis of the story called “The Story” and then segues into “The Life.” It is a good place to start if you don’t know Mansfield’s work, although you will need to get a copy of The Collected Stories in order to read the stories in their entirety. It is also a good place to start rereading, a worthy project even if you think you know those stories. For you will find, as I did, that several are even richer than you remembered.

Here is a passage from “At The Bay,” not one of the stories Harman cites, but one of my favorites. It gives you an example of what Mansfield did so well:

He snatched his bowler hat, dashed out of the house, and swung down the garden path. Yes, the coach was there waiting, and Beryl [his sister-in-law], leaning over the open gate was laughing up at somebody or other as if nothing had happened. The heartlessness of women! The way they took it for granted it was your job to slave away for them while they didn’t even take the trouble to see that your walking-stick wasn’t lost….

“Good-bye, Stanley,” called Beryl, sweetly and gaily. It was easy enough to say good-bye! And there she stood, idle, shading her eyes with her hand. The worst of it was Stanley had to shout good-bye too, for the sake of appearances. Then he saw her turn, give a little skip and run back to the house. She was glad to be rid of him!

Yes, she was thankful. Into the living room she ran and called “He’s gone!” Linda [his wife] cried from her room: “Beryl! Has Stanley gone?” Old Mrs. Fairfield appeared, carrying the boy in his little flannel coatee.

“Gone?”

“Gone!”

Oh, the relief, the difference it made to have a man out of the house. Their very voices were changed, as they called to one another; they sounded warm and loving as if they shared a secret. Beryl went over to the table. “Have another cup of tea, mother. It’s still hot.” She wanted somehow to celebrate the fact that they could do what they liked now. There was no man to disturb them; the whole perfect day was theirs.

Writer Katherine Mansfield in 1917. Her best work shimmered with an unusual tenderness, filled with characters that could creep into your heart.

Kathleen Beauchamp was born in Wellington, New Zealand, to a wealthy family; her father Harold was a banker and one of the richest men in the country. Her mother Annie was a distant mother who would prove a crushing disappointment when her love was most needed. In this rather conventional family of four sisters and the youngest, a brother named Leslie but always known as Chummie, there was the outlier in the middle: a plump, headstrong girl who took many names — Russian, Maori, Shakespearean, mythical — until she finally settled on Katherine when she came to England for good. By the time Katherine was sent to an all-girls school called Queens College in London in 1903, she was known as the “wild” one. She had had at least two lesbian relationships during her teens, and thought of herself as a cultural Bohemian destined by her talent and interests to spread her wings far from home. Although she was not exactly welcomed at school in London, she knew she had found her milieu and developed a love/hate relationship with a woman named Ida Baker (whom she called her “wife”), which would last for the rest of her life. After returning to Wellington, where her parents hoped she would settle down and find a husband, she convinced her father to let her go back to England in 1908. She never returned home, although over time New Zealand became increasingly important in her best work, like “Prelude” and “At the Bay.”

From childhood on she was a chameleon, sometimes demure and charming, sometimes flamboyant and loud, sometimes angry and virtually uncontrollable. Eerie changes of mood were accompanied by strange costumes; she saw clothes as “a silent reflex of the soul … [saying later] I like Life in my clothes.” Her first husband said she dressed “like Oscar Wilde”; others recalled her elaborate Oriental dresses and cheap accessories and the odor that floated about her. Even her rooms — and there were many because she was always on the move — were decorated in styles that were hardly conventional.

Back in England in 1909 she fell in love with Arnold Trowell, managed to get pregnant by his twin Garnet, and married George Bowden to legitimize the child. She left him on her wedding night, had a late miscarriage, and subsequently divorced Bowden, the marriage never having been consummated. During this mess her mother came to London and took her to Germany for “treatment.” She left her at a spa and, when she got home, wrote Katherine out of her will. To make matters worse, Katherine then became involved with a Pole named Florian Sobienowski, who introduced her to Chekhov’s stories and also gave her the gonorrhea that would “linger malevolently”in her body and create chronic health problems for the rest of her life. Because there were not yet any antibiotics to treat venereal disease, she suffered increasingly from pain in her joints. Her heart was compromised, so she became more susceptible to the tuberculosis that eventually killed her. And then there was Chummie’s senseless death in a training accident at Ypres at the beginning of the war, when he was “blown to bits.” He was her best-loved sibling with whom she had made plans to grow old; it was a loss from which she never recovered.

Katherine met the man who was to become her second husband at an Oxford dinner party in 1911. He was John Middleton Murry, still an undergraduate, but within a year of their meeting he had dropped out of Oxford and moved in with her. Years later he said, “I was secretly astonished that she had chosen me.” For by now she was a slender beauty with a magnetic appeal to both men and women. Although Murry never fulfilled his own dreams of becoming a great writer and proved a somewhat absent husband — actually and sexually — he was a good editor and his various editorial positions and connections in the London literary world helped get his far more talented wife published while she was alive. He was also a diligent keeper of her legacy after she died. We are in his debt for not only the stories, but the journals and letters and reviews, which he saw through to publication until his death in 1957. Some people think he projected a false picture of Katherine, and that is true; she was far too mysterious for him to plumb completely. Or that he became famous on her coattails. Also true. But whatever his motives, he made sure that people didn’t forget her, and for that we must be grateful.

Katherine Mansfield and John Middleton Murry at unknown location, circa 1920. Taken by an unknown photographer.

When her divorce from Bowden came through in 1918, Katherine and Murry married, but from the time they started living together until her death it was a strange arrangement. Both had affairs and deep friendships with other men and women; there were angry partings and unfulfilled yearnings (mostly on her part, for she was far more interested in sex than he was) and wildly happy reunions. There were also good times when she could settle in and write in what seemed, at least for a while, a peaceful home. And unrealistic hopes for the future, which included a house and garden and even a child. There were times when she hated Murry, yet her longing for him — which often took her by surprise — was a persistent thread in their life together. Yet when he managed to come to her it was usually too late. There was also anxiety about money. Although she received an allowance from her father, it was never quite enough. As she told Murry, “I can’t live poor … and work, too. I don’t want to live rich — God forbid— but I must be free.” And, always in the background, there was Ida Baker (sometimes called Lesley Moore or L.M., to Mansfield’s family and friends); she was, in the end, the most loyal companion of all. To add to the mix for anyone who has tried to parse Mansfield and Murry’s marriage is D.H. Lawrence’s Women in Love, the novel that so many thought was a roman à clef about Lawrence and Frieda and Katherine and Murry, but that may have been more fiction than fact.

What was all too true was that they led a chaotic life. Their years of marriage were filled with doctors and also quacks — Katherine was always looking for a cure — and restless moves from the London winters to places where warmth and sun might give her the energy to write the stories she so badly wanted to write. Harman is a good guide through all that mayhem and an astute reader of the stories. She makes important connections — for example, that Katherine worked as a movie extra and was fascinated by the cinema, thus her ability to create film clips with words, to show the self as “multiple and shifting.” Or pointing out Katherine’s early exposure to Chekhov and the other Russian writers (beginning to be translated by the formidable Constance Garnett) who so clearly influenced Katherine’s work. Or that Katharine could see van Gogh “shaking free” in his paintings, which gave her the courage to do the same in her stories.

Although the book is not exactly chronological, Harman gives us a good sense of the trajectory of Katherine and Murry’s life, not only looking at their families and close friends, like Lawrence and Frieda, but also at people on the edge, like Virginia and Leonard Woolf. Initially, they were somewhat shocked by the coarse strain in Katherine’s personality, but the pair valued her vision and published “Prelude” at their Hogarth Press. The passages about Virginia and Katherine are especially touching: Here were two women who were doing the same thing, who prized their work above all, and who could talk to each other with a special kind of intimacy. Harman reminds us of the value of Katherine’s clear-eyed review of Woolf’s Night and Day. She saw it as very old-fashioned and not good enough — “the novel can’t just leave the war out,” Katherine said to friends — a reaction that probably led to Woolf’s sharp turn in another direction with Mrs. Dalloway. I have always felt that Woolf’s novel (published in 1925) owed something to Katherine’s story “The Garden Party” (published in 1922). They share a similar theme: the death of a lower-class citizen disturbs the revels of the upper classes. Moreover, no one has ever forgotten that Virginia said, “I was jealous of her writing. The only writing I have ever been jealous of.”

Although the book is not exactly chronological, Harman gives us a good sense of the trajectory of Katherine and Murry’s life, not only looking at their families and close friends, like Lawrence and Frieda, but also at people on the edge, like Virginia and Leonard Woolf. Initially, they were somewhat shocked by the coarse strain in Katherine’s personality, but the pair valued her vision and published “Prelude” at their Hogarth Press. The passages about Virginia and Katherine are especially touching: Here were two women who were doing the same thing, who prized their work above all, and who could talk to each other with a special kind of intimacy. Harman reminds us of the value of Katherine’s clear-eyed review of Woolf’s Night and Day. She saw it as very old-fashioned and not good enough — “the novel can’t just leave the war out,” Katherine said to friends — a reaction that probably led to Woolf’s sharp turn in another direction with Mrs. Dalloway. I have always felt that Woolf’s novel (published in 1925) owed something to Katherine’s story “The Garden Party” (published in 1922). They share a similar theme: the death of a lower-class citizen disturbs the revels of the upper classes. Moreover, no one has ever forgotten that Virginia said, “I was jealous of her writing. The only writing I have ever been jealous of.”

Here is an example that Harman has chosen from “Prelude” which gets inside Linda’s head about her sexual relationship — very modern for its time — with her husband Stanley:

He was too strong for her; she had always hated things that rush at her, from a child. There were times when he was frightening. When she just had not screamed at the top of her voice: “You are killing me.” And at those times she had longed to say the most coarse, hateful things…

“You know I am very delicate. You know as well as I do that my heart is affected, and the doctor has told you I may die at any moment. I have had three great lumps of children …”

Yes, yes, it was true. Linda snatched her hand from her mother’s arm. For all her love and respect and admiration she hated him. And how tender he was after times like those, how submissive, how thoughtful. He would do anything for her; he longed to serve her … Linda heard herself saying in a weak voice:

“Stanley, would you light a candle?”

And she heard his joyful answer: “Of course I will, my darling.” And he leapt out of bed as though he were going to leap at the moon for her.

Harman’s excellent book deals only with the stories, but for those who want to explore more about Mansfield, there are also the journals and letters and reviews. Katherine’s wit and intelligence and occasional mean streak are on full view there and make very entertaining reading. Here she is on Forster’s Howard’s End: “I can never be perfectly certain whether Helen was got with child by Leonard Bast or by his fatal forgotten umbrella. All things considered I think it must have been the umbrella.”

But what is, in the end, most moving is this young woman’s dedication to literature, to her dream of being part of that great river of literary works that runs through the ages. Even when she was close to dying, she was “full of an eager desire to learn, analyze and enjoy” as she read Shakespeare’s plays. She thought of the masters — Chaucer, Shakespeare, Marlowe, and even Tolstoy — as her “daily bread.” She told her husband’s brother, Richard, “I find that if I stick to [them] I keep much nearer what I want to do than if I confuse things with reading a lot of lesser men…. [The] more one lives with them the better it is for one’s work. It’s almost a case of living into one’s ideal world — the world that one desires to express.”

The bravery of that sentiment is stunning, and in keeping with her extraordinary, far too short life. We can only wonder what she might have given us had she lived a normal life span, but we must cherish what we have, as Claire Harman has done so beautifully.

Roberta Silman is the author of five novels, a short story collection and two children’s books. Her latest, Summer Lightning, has been released as a paperback, an ebook, and an audio book. Secrets and Shadows (Arts Fuse review), is in its second printing and is available on Amazon. It was chosen as one of the best Indie Books of 2018 by Kirkus and it is now available as an audio book from Alison Larkin Presents. A recipient of Fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts, she has reviewed for the New York Times and Boston Globe, and writes regularly for the Arts Fuse. More about her can be found at robertasilman.com and she can also be reached at rsilman@verizon.net.

Just a great essay, Roberta, packed with the most interesting information about Mansfield. What a complicated person, what a fabulous short story writer.