Jazz Remembrance: Tribute to Wayne Shorter

One of the true masters of jazz, Wayne Shorter, passed away during the early hours of March 2. The magazine’s writers quickly gathered to express their appreciations of Shorter’s innovations and his long life of constant creativity.

— Allen Michie

Wayne Shorter on tour with Marcus Miller’s “A Tribute To Miles” in 2011. Photo: Facebook

Shorter Shares Circular Drops of Wisdom

In 2008, when I called Wayne Shorter at his L.A. home on the eve of Election Day, I could hear CNN buzzing in the background. “It’s going around and around, and occasionally you hear something,” he said of the campaign coverage as he turned down the TV. “You go in circles when you want to clean something too.”

Shorter, then 75, also tended to speak in circles during elliptical interviews that would spin into philosophy and film more than music theory or his legacy as a jazz pioneer with Miles Davis and Weather Report. But, along the way, his audience could glean some enlightened wisdom that framed a broader picture.

“Music is useless unless you see what the process of doing it means to human existence,” the saxophonist told me, a few weeks before a Boston date with his quartet of pianist Danilo Perez, bassist John Patitucci, and drummer Brian Blade.

In that esteemed group, Shorter pursued a fresh musical language where they reconfigured compositions on the fly — and drew on fearlessness. “Perfection is like viewing a statue,” he said. “It’s perfect, but it’s the opposite of potential.”

The quartet usually began concerts with a wily open-improv piece called “Zero Gravity” for good reason. “It’s totally different every night,” Shorter said. “It’s not something like going ’round ‘Round Midnight,’ and you ad-lib differently.”

His inspiration came from thought-provoking books and movies. Shorter recalled how he and Davis, a fan of film and boxing, connected to the cadence of dialogue by John Wayne and Humphrey Bogart. “Miles would say ‘Can you play that?’” he said. “Some of that stuff that Miles was playing, now that I’m thinking of it, also sounded like the motor of [his] Ferrari. And he’d play notes as if he were boxing.”

A car engine and boxing — ah, two other things that incorporate circular motions to create a desired effect. “Jazz is just a synonym for creation,” Shorter said. “Let’s go into the unknown, because ‘into the future’ sounds too elitist.”

— Paul Robicheau

Wayne Leaves Town

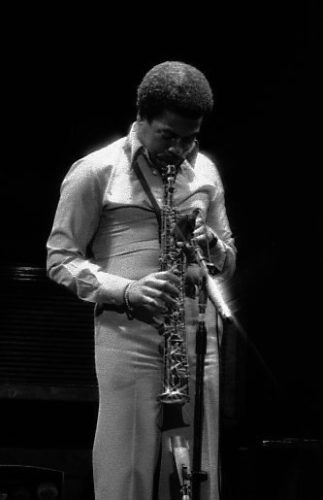

Wayne Shorter performing with Weather Report in 1977. Photo: Wiki Common

Pianist Tommy Flanagan was fascinated with Lester Young. He told me about going with a friend to visit “Prez” in his apartment across the street from Birdland and being greeted by the man wearing a shirt and tie and his iconic porkpie hat, but without pants. Even his walk, which Flanagan described as tripping and others as mincing, was unique. What made me think of this is the passing of the great Wayne Shorter. In 1959, the year of Shorter’s first recordings both as a leader and as sideman to Wynton Kelly and Art Blakey, Blakey recorded Shorter’s composition “Lester Left Town.” Despite the circumstances, it wasn’t a tragic piece. Rather, its two bars of chromatically descending quarter notes captured, I believe intentionally, Young’s walk. This must have been the way Lester wanted to leave town, I thought, with class and precision.

I first heard Shorter about seven years later, when he was with the Miles Davis Quintet, which he helped transform through his compositions like “Footprints,” “Nefertiti,” and “E.S.P.” What I remember most about Shorter that night was him leaning up against a post while Herbie Hancock and Tony Williams wildly played off each other, riding into some distance only they could fathom. Except that one got the feeling that Shorter followed, and maybe even predicted it all. When he started to play, it was with what seemed to me clear intention.

I think of Wayne Shorter as much as a composer as a saxophonist, stunning though he could be as a player. He has his own kind of hefty tenderness, as he demonstrated on his “Infant Eyes,” a composition marked by a sort of sweet sobriety. It’s found on the album Speak No Evil, which is also notable for the title cut, and for “Wild Flower,” where Shorter floats over the beat in a manner that would have made Lester Young proud. Others are writing about his later career. For now, I am remembering hearing him in Ann Arbor with Weather Report, where he seemed almost swamped by the electronics. In mid-concert, he imposed a hush and played a ballad, a good old-fashioned 32-bar piece. He was always looking forward, so he could afford a piece of nostalgia.

— Michael Ullman

An Uncommon Musician

His passing resonates.

The only time I heard Wayne Shorter play live was in the summer of 1971 when an early version of the group Weather Report performed on the Boston Common. At that point, my knowledge of jazz came primarily out of Miles Davis’s Bitches Brew, on which Shorter and his Weather Report band mate Joe Zawinul had played, and just a smattering of late John Coltrane albums, the latter both impressive and bewildering to me.

The only time I heard Wayne Shorter play live was in the summer of 1971 when an early version of the group Weather Report performed on the Boston Common. At that point, my knowledge of jazz came primarily out of Miles Davis’s Bitches Brew, on which Shorter and his Weather Report band mate Joe Zawinul had played, and just a smattering of late John Coltrane albums, the latter both impressive and bewildering to me.

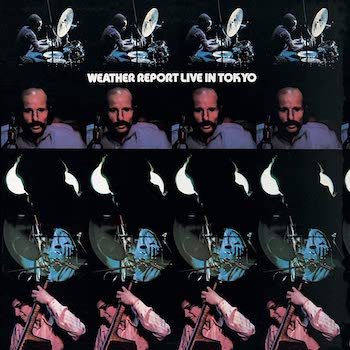

If I remember correctly, the opening act was Maynard Ferguson’s Big Band, in which Shorter and Zawinul had played years before. After Ferguson and company’s hard-charging, in-your-face riffs and soaring solos echoed across the Common, I must say that it was a bit of a letdown to hear Weather Report work much softer, quieter, and more spacious arrangements. I remember hearing a guy in the crowd loudly request at one point that the group “play something nasty.” They never quite did on this occasion. (Check out 1972’a Weather Report Live in Tokyo where things do get heated.)

But the group intrigued on subtler levels. The relatively delicate interaction of the players — Shorter (soprano sax), Zawinul (keyboards), Miroslav Vitouš (acoustic bass), Alphonse Mouzon (drums), and Dom Um Ramão (percussion) — eventually won me over. They were on the brink of something special, and Shorter already seemed the distinguished musician he would continue to be for decades to come.

Once that Wayne Shorter sound got in my ears, I was never again left without a place to go, if now only on recordings, to hear an amazing jazz master at work.

— Steve Feeney

Wayne Shorter and Joni Mitchell. Photo: Lester Cohen

The Joni Years

It’s well known that Wayne Shorter played on some of Joni Mitchell’s albums and that the two artists enjoyed many years of friendship. It was Herbie Hancock who made the match, who convinced Wayne that Joni’s music was worthy of his attention and contribution. Yet I was surprised when I took inventory and realized that from 1977 to 2002, Wayne appeared on 10 consecutive Joni studio albums — out of 19 overall. Their collaboration was the rule, not the exception. And while it would be foolish to assert that his best playing is to be found in and over her grooves, he proved to be an adept sideman for the singer-songwriter, helping to blur the lines around jazz, rock, electronic music, and that label-defying genre that Joni created and remains its sole exponent. With his beautiful tone and expressive melodic twists, Wayne added color and grace to her music.

It would be hard to single out a single performance, but my choice is a surprising one. His first album of hers was Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter, which features the 16-minute “Paprika Plains,” an impressionistic dream-trance composition that, for the first 13 minutes, features Joni singing and playing piano with occasional orchestral accompaniment. The extensive lyrics are all sung when Wayne finally comes in, followed by drummer John Guerin and then bassist Jaco Pastorius. Wayne solos from 13:45 to the end of the song. The tension that the band breaks after 13 minutes of sparse music and stream-of-consciousness vocals is palpable, and Wayne’s soprano sax is a relief, a balm, like aloe on a sunburn. His solo dances us out of the austere setting Joni created, quenching our thirst like a long-awaited rain. As with all his best playing, it’s something that we feel deeply and that leaves us with a sense of gratitude.

— Jason M. Rubin

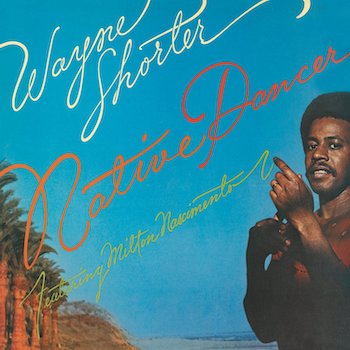

When Wayne Met Milton

A decade after Stan Getz’s collaboration with Brazilians Antônio Carlos Jobim and João and Astrud Gilberto lit up the charts with “The Girl From Ipanema” and sparked the rage for all things Bossa Nova, another jazz saxophonist dipped into the music of Brazil and came up with gold. Though it made a more limited splash, Native Dancer, Wayne Shorter’s 1975 masterpiece featuring Milton Nascimento, had a deep impact in certain pockets of the jazz world, and it opened up northern ears to the sounds of the brilliant singer-songwriter and his post-Bossa peers. It also features some of Wayne’s own most beautiful compositions.

A decade after Stan Getz’s collaboration with Brazilians Antônio Carlos Jobim and João and Astrud Gilberto lit up the charts with “The Girl From Ipanema” and sparked the rage for all things Bossa Nova, another jazz saxophonist dipped into the music of Brazil and came up with gold. Though it made a more limited splash, Native Dancer, Wayne Shorter’s 1975 masterpiece featuring Milton Nascimento, had a deep impact in certain pockets of the jazz world, and it opened up northern ears to the sounds of the brilliant singer-songwriter and his post-Bossa peers. It also features some of Wayne’s own most beautiful compositions.

Native Dancer may be filed under “Wayne Shorter,” but five of its nine tracks are by Milton. By 1969 Milton had recorded the album Courage at Rudy Van Gelder’s studio in New Jersey, produced by Brazilian export Eumir Deodato, with Wayne’s Miles Davis Quintet mate and friend Herbie Hancock, as well as fellow Brazilian Airto Moreira (Miles Davis, Weather Report). I’ve read two accounts of how Wayne got the idea to record with Milton: Nate Chinen’s New York Times obituary credits it to Wayne’s second wife, Ana Maria, who grew up in Portuguese-speaking Angola, and writer Joe Nocera quotes an interview Milton’s longtime friend and pianist Wagner Tiso gave to pianist Cliff Korman (an American export to Brazil), where Tiso claims Wayne heard Milton during a Weather Report tour in Brazil and immediately wanted to record his “sound.”

You can’t hear the opening notes of the album’s first track — Milton’s “Ponta de Areia” — without being struck by that otherworldly falsetto, doubling the simple plinking of melody on the piano. We soon hear the full play of his voice, and its ease of traversal from baritone low to ethereal top. Nowhere is that breathtaking range more apparent than in Milton’s “Miracle of the Fishes” (“Milagre dos Peixes”): he sings the verses low and lets his airy falsetto float above Wayne’s muscular solo, which — as if to mimic Milton — switches from tenor to soprano about two-thirds of the way through.

Wayne Shorter, visited at home in L.A. by Milton Nascimento in October 2022 during Milton’s farewell tour. Photo: Augusto Kesrouani Nascimento

It’s truly ear-opening to hear how well the Brazilian and jazz strands intertwine throughout the album. Hancock’s pianos, acoustic and electric, mesh easily with Tiso’s organ and electric piano, especially on Wayne’s classic “Beauty and the Beast”; Airto puts his pandeiro spin on the tune’s “chorus” sections, while drummer Robertinho Silva softens the funk under the yearning, melodic “verses.” Wayne’s tenor answering Milton’s lush sound on his gorgeous ballad “Tarde” strikes me as a worthy update of the partnership of Coltrane and Johnny Hartman on their famous album. And delicate Bossa Nova rhythms alternate with funkier sections on “Ana Maria,” Wayne’s (to me) most beautiful and haunting song on this or any of his albums.

Clearly, Wayne knew what he wanted. Nocera’s article includes an excerpt from an interview where Wayne explained (to Korman) his intent: “‘The disc is important because it shows how to bring two views of music together without one being subordinated to the other,’ he said. ‘We didn’t want Milton to imitate jazz, and I wouldn’t have been able to imitate Milton. We succeeded in doing something in which each complemented the other.’”

Succeeded is right. The following year, Wayne and Herbie, along with Silva and Airto, appeared on Milton’s release Milton (1976). Wayne and Milton continued their friendship and musical connection. Jazz and Brazilian music continue to complement each other.

— Evelyn Rosenthal

“When all my dime dancing is through …”

One of the distinctive riffs on one of the signature albums of the late ’70s is Wayne Shorter’s brief, full-bodied solo on Steely Dan’s Aja. Donald Fagen and Walter Becker were hip and notoriously demanding guys when it came to knowing what they wanted. Tales are legion among musicians of being asked to perform take after demanding take during a recording session.

The story of Wayne Shorter’s contribution on the album’s title song is different. Marc Myers, longtime Jazz Writer for the Wall Street Journal, provided the story. Writing in 2011, on his blog JazzWax, Myers says he talked to Dick LaPalm, a recording business heavy who’d worked with Nat King Cole, Sarah Vaughan, and the Modern Jazz Quartet. In 1977, when Fagen and Becker were in the process of recording their sixth and most ambitious studio album, their producer, Gary Katz approached LaPalm.

“Donald and Walter want Wayne to do the solo on the title track. Will you call him?” Katz then confessed to LaPalm that it was a gig Shorter had turned down a few days earlier.

But LaPalm, knowing the band’s music, and being a friend of Shorter’s, agreed to ask. It turns out there’d been a misunderstanding. Shorter didn’t know the group and had lumped it together in his mind with any number of loud rock and roll bands. When LaPalm made clear that wasn’t the case, Shorter signed on.

LePalm recounts: “When Wayne arrived at the Village Recorder, he asked if before he got started he could chant.” Along with his openness to crossing musical boundaries, Shorter’s spirituality was a big part of who he was. “I sent him into Studio C. When he was done, he came into Studio A. [He] did his solos — six passes in all. He loved the music, and was gone in 35 minutes. The guys were sitting around watching, stunned. After he left, Donald and Walter spliced together the six passes, and that’s what you hear on the album.”

Liner notes for the disk by “Michael Phalen” (long assumed to be Becker and Fagen themselves) call the song “Aja” an “ambitious work in which a latin-tinged pop song is inexplicably expanded into some sort of sonata or suite. The result is a rambling eight-minute epic highlighted by Wayne Shorter’s stately rhapsodic solo…”

A Billboard reviewer was more succinct in calling Shorter’s solo “nothing less than dreamy.”

— David Daniel

Weather Report at Boston’s Orpheum, 1980. Photo: Paul Robicheau

Awfully Glad I Met You, Cheerio and Tootle-loo

Wayne Shorter was one of jazz’s greatest composers, he was a highly responsive team player in any ensemble, and he made forward-thinking music that audiences didn’t catch up to until years later. So it comes as a head-scratching surprise that in the middle of Weather Report’s live album 8:30 (ARC, 1979), bracketed by up-tempo electronic jams, Shorter takes an extended unaccompanied solo on a nostalgic tune from 1937.

Wayne Shorter at Great Woods jazz festival in 1988. Photo: Paul Robicheau

“Thanks for the Memory” debuted in Bob Hope’s movie The Big Broadcast of 1938. It was a hit, and he regularly used it as a closer for his standup performances, USO shows, and TV specials. It’s been covered by many singers of standards, including Frank Sinatra and Ella Fitzgerald, and you can find conventional instrumental versions from the likes of Benny Goodman and Ray Conniff. But Wayne Shorter? At a Weather Report concert?

As Shorter once said, “The word ‘jazz,’ to me, only means ‘I dare you.’”

Shorter begins with single honks on the tenor, followed by rapid bebop lines. He winds his way down several arpeggios, reaching up and cascading back down, exploring the range of his horn. It takes a while for the melody to appear, and it turns out to be a good match for Shorter’s style: the construction of simple riffs — repeating up whole steps and followed by a wide octave interval — really isn’t too different from something Shorter might have written, like “Nefertitti.”

He deconstructs and reassembles the song, juxtaposing expressive long tones with fragmented slivers of sound. The tempo drags, then suddenly races. The humor is always there as Shorter toys with the wide intervals and sees if he can turn his tenor sax into a kind of postmodern calliope. There’s an underlying sense of irony as a nostalgic song about memory becomes a futuristic excursion that owes more to Sun Ra than to Bob Hope.

Shorter doesn’t end his solo — he just slowly strays from the microphone, letting us continue the solo in our minds.

Thanks for the memories, Wayne.

— Allen Michie

Wayne Shorter — How many other great saxophonists have been so willing to support the leadership of others?

As a tenor player, he had a beautiful “cry”

No other musician chose to create as Wayne Shorter did. I have three observations about his distinctive importance.

First, Shorter owned a sound on each of his saxophones that was instantly identifiable. As a tenor player, he had a beautiful “cry” — it reminded me of the singing quality I associate with the legendary Texas Tenors (not bad for a fellow from New Jersey). And then, as a soprano player in John Coltrane’s wake, he built on the Master’s inspiration and made the straight ax his own: even more distinctive, even more vocal than his tenor. It’s no wonder that singers loved having him contribute to their recordings — Milton Nascimento, Donald Fagen, Joni Mitchell, and Norah Jones, just to name four.

Second, in a musical form where ego seems to be a prerequisite, Shorter was the Great Collaborator. It seems that for the most part he preferred to let others stand out front, content to be the distinctive composer within their ensembles. He served one of the longest tenures of all the legendary side players who contributed to Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers. He was integral to Miles Davis’s late 1960s quintet — but he never competed for attention with the leader or with Herbie Hancock and Tony Williams, the spark plugs of that band’s relentless innovation. Perhaps no other person could have filled the saxophone chair in Weather Report for so long, letting Joe Zawinul lead and define the band and (later) ceding even more of the spotlight to Jaco Pastorius.

In Shorter’s own Blue Note recordings as a leader during the Blakey and Davis years, and in his four post–Weather Report recordings as a leader, he is a more forward presence, but he permits the music to be crucially shaped by other players and his producers. In his own working group of the 21st century, he was never the Saxophone Colossus à la Sonny Rollins, but rather one of four creators, and he gave Danilo Pérez pride of place in that band with nearly the status of co-leader. And how many other great saxophonists have been so willing to support the leadership of others? Shorter collaborated with Lee Morgan, Freddie Hubbard, Gil Evans, Carlos Santana, Michel Petrucciani, John Scofield, and many others whose names you will not know.

Third, let me build on the observations of my colleagues Michael Ullman and Allen Michie about the importance of Shorter’s compositions. Even though there are a handful of classic Shorter tunes in every Real Book, I want to offer a list of many more. Over 40+ years, Shorter consistently created vivid structures for improvisation that had a magical circularity — time after time, you’d hear one of his tunes where the last note of a theme seemed to lead inevitably back to the start of the composition. That circularity eventually was recognized directly by Miles Davis, who paid Shorter the ultimate compliment — playing “Nefertiti” and “Sanctuary” without offering any improvised statement of his own, just letting those great themes ring and ring and ring.

You’ll see some well-known titles below, but look at all the others, the names of which almost create a poem in themselves. They demonstrate the riches of Wayne Shorter’s work and offer a challenge to those who would keep his legacy alive. Don’t just play “Lester Left Town” or “Footprints.” Go deep into the oeuvre and find a tune you can own and enrich. There are plenty to choose from.

Here is a testament (chronological by recording date) to a career of remarkable fertility:

11/1959: Black Diamond, Africaine, Lester Left Town

3/1960: The Chess Players

8/1960: Giantis, Noise in the Attic

10/1960: Pay as You Go, The Albatross

11/1961: Dead End, Devil’s Island, Reincarnation Blues

6/1963: One by One

2/1964: Hammer Head

8/1964: Juju, Yes or No

12/1964: Witch Hunt, Speak No Evil, Infant Eyes, Wild Flower

1/1965: E.S.P. (co-credited to Miles Davis)

3/1965: Lost, The Big Push, The Soothsayer

6/1965: Penelope

10/1965: Chaos

2/1966: Footprints, El Gaucho

10/1966: Orbits

3/1967: Go

5/1967: Pee Wee

6/1967: Nefertiti, Pinocchio

2/1968 & 8/1969: Sanctuary

8/1970: Calm

2/1971: Tears

9/1974: Beauty and the Beast, Ana Maria, Diana

1975: Lusitanos

12/1975–1/1976: Elegant People

10/1976: Palladium

1981: When It Was Now

1983: Predator

1984: Face on the Barroom Floor

1985: Shere Khan the Tiger

1986: Mahogany Bird

1988: Cathay

1995: On the Milky Way Express, Midnight in Carlotta’s Hair

2002: Angola

2004: Adventures Aboard the Golden Mean aka S.S. Golden Mean

— Steve Elman

Very good.

Beautiful writing all around.

Guess I go back further than others, maybe, in first hearing and being captured by Wayne as a player and composer, back to early 60’s–pre Miles for the history. No one in these well meant and written tributes refers to Shorter being with Maestro percussionist Art (Buwana) Blakey, his chief composer and effectively leader — correct me if I’m wrong writers — and for more than a record date or two. Classic Hard-Bop that was never equaled, no insults to the great leader, pianist Horace Silver bands, that carried as much weight in the Jazz world then as the future Miles Quintet with Wayne. Betcha, Miles “stole” him from Blakely cause he heard his genius and wanted it for himself (smile). My first hero leading me to ‘Trane, Albert, the Sun, etc,: someone had to be the “first”!

Late entry by Steve Elman does mention Wayne’s tenure with Blakey being one of the longest of all his sidemen. So much to cover in such a long and rich career! Thanks for your comment.

It is very beautiful article. Thank you, Allen. Specially, moved by the story of Native Dancer. I saw the video of Milton Nascimento final concert in Brazil. But also moved to teard for me 2 shot Wayne and Milton after his Cali concert.

Very glad you liked the Native Dancer piece. I was lucky enough to see Miton on his farewell tour here in Boston–Esperanza Spalding was there, and she sang “Ponta de Areia” with him! And that photo of Wayne and Milton is so beautiful, taken by Milton’s son.