Opera Album Review: Carl Maria von Weber’s “Der Freischütz” Finally Makes Sense

Conductor René Jacobs restores missing bits of this beloved opera’s story, and Ukrainian soprano Kateryna Kasper glows as Ännchen.

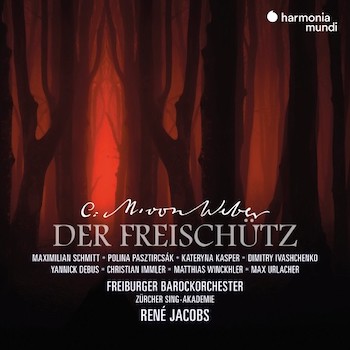

Carl Maria von Weber: Der Freischütz (1821)

Polina Pasztircsák (Agathe), Kateryna Kasper (Ännchen), Maximilian Schmitt (Max), Yannick Debus (Kilian), Matthias Winckhler (Kuno), Dimitry Ivashchenko (Kaspar).

Freiburg Baroque Orchestra and Zurich Sing-Akademie, cond. René Jacobs.

Harmonia Mundi 902700.01 [2 CDs] 138 minutes

How do you make a two-hundred-year-old work feel fresh again? The standard solution in opera houses is to update the sets and costumes, and the characters’ gestures and such, the aim being to make the events feel more like those in our own world. The benefits and limitations of such “strong” or “conceptual” directorial decisions have been much debated. One disadvantage: making an on-stage tyrant remind us of Hitler or Mussolini can end up trivializing history without doing anything to illuminate the work being performed.

Less often do productions try something that is perhaps riskier: grounding the production ever-more-deeply in the culture of its day. This is what René Jacobs (once one of the world’s leading countertenors, now a prominent conductor) has done with Carl Maria von Weber’s oft-performed and -recorded opera Der Freischütz. The result is an admirable and consistently enjoyable rendering of the work, and a recording that leaps into the top tier.

Weber’s Der Freischütz 1821 is one of the earliest German operas in the standard repertory, coming after two by Mozart (The Abduction from the Seraglio and The Magic Flute) and one by Beethoven (Fidelio, which exists in several distinct versions) and before the numerous ones by Wagner and Richard Strauss (plus two lighter works Johann Strauss, Jr.’s Die Fledermaus, and Franz Lehár’s The Merry Widow).

Der Freischütz quickly conquered the German-speaking world: Heine reported that people were whistling its tunes in the street. But it took longer to be appreciated elsewhere, in large part because it uses spoken dialogue. In some foreign theaters, versions were used that contained recitatives, composed by someone else for the purpose. Berlioz wrote the recitatives needed for a production at the Paris Opéra in 1841. He orchestrated (brilliantly) Weber’s piano piece Invitation to the Dance in order to provide music for the ballet that the Opéra patrons absolutely demanded in every opera. Most recordings, of course, use the original German version, though often trimming the spoken dialogue a good bit.

On this new recording, conductor René Jacobs goes much further. He and his team have inserted additional spoken dialogue and have even created three new musical numbers; most of this is based on passages, early in Friedrich Kind’s libretto, that Weber decided to omit.

Thus the back story of Weber’s opera is enacted before our ears, through a spoken conversation between Agathe and the Hermit (the latter gives her, for protection, the white roses that will recur near the opera’s end)—a conversation that pauses for a new aria for him and for a new duet for the two of them (both numbers are based on material elsewhere in Weber’s opera).

The third new musical number is for Agathe’s father, Kuno. Its music is that of a drinking song that Schubert composed seven years earlier for a now-little-known spoken-dialogue opera, Des Teufels Lustschloss (The Devil’s Pleasure Palace). The music in no way obtrudes, being stylistically consistent with Weber’s in this opera.

Conductor René Jacobs — Would you want his version to be your first or only recorded version of Weber’s opera? Actually, you might.

These additions were concocted by Jacobs himself, and I hope he publishes them for use by other conductors and opera companies. Some opera houses have carried out a similar plan but in a modest fashion: An actor reads the words of the Hermit/Agathe scene aloud after the overture. But, as Jacobs points out in his booklet-essay, important passages in the opening of Kind’s libretto are in verse and were clearly intended by him to be set to music. Indeed, there was one specific previous attempt at setting the missing parts of the libretto (by Oskar Möricke: Lübeck, 1893).

The booklet helps the listener by including a complete rendering of the libretto as adapted, plus fine translations into French and English.

In addition, much care has been taken to turn the recording into a kind of radio-opera experience, in which major points are made evident to the ear rather than the eye. For example, various stage directions are adapted to become spoken comments from the evil spirit Samiel and his fellow demons; these characters often speak their nasty, threatening remarks in a half-whisper that is enabled by close microphone placement. And there are some high-tech sound effects (an eagle, shot in the air, whistles as it plummets to earth and then lands with an enormous thud) and simple, stagy ones (the howling of wolves, created by members of the chorus).

The result is an invigorating experience and an utterly persuasive one, in part because the materials that it inserts are consistent (though not always identical) with those of the opera’s own day. Even the idea of including a musical number by another composer was not anathema in early-Romantic opera houses. Rossini’s comic operas often had at least one aria composed by an assistant. Also, some singers carried a favorite aria of theirs with them to add to this or that other opera in which they’d be singing.

In short, we have here a high-concept rethinking of a standard work, but that concept is deeply informed by practices of the day, whereas so many stagings nowadays go counter to crucial musical, theatrical, and aesthetic premises of a work.

Would you want Jacobs’s recording as your first or only recorded version of Weber’s opera? Well, actually, you might. And you would, I imagine, be happy for years. (I’ll propose some alternatives at the end.) The singing is generally fine. At times the Max (Maximilian Schmitt) and Kaspar (Dimitry Ivashchenko) each have a touch of wobble. The Agathe (Polina Pasztircsák) is the biggest disappointment: her high notes gleam, but the low ones are thin, and her coloratura can be more aspirated than clearly pitched.

The most treasurable role-assumption here comes from Kateryna Kasper as Ännchen. Her voice is richer than that of the Agathe, and is fuller the deeper she goes. (Her speaking voice, too, is lower than Agathe’s.) This is consistent with the fact that her vocal line is below Agathe’s when they sing together, and it forms a welcome change from German opera-house tradition of making Ännchen into an operetta soubrette.

I have generally dreaded Ännchen’s second aria (the ghost story), but Kasper here carries it out with exquisitely apposite diction and an impressive variety of vocal devices. I have a feeling she’d make a great Agathe, and hope she is given the chance someday.

I should also name two performers who make their secondary roles feel absolutely essential: the great Lieder singer Christian Immler as the Hermit and Max Urlacher in the expanded spoken role of Samiel. A few of the cast members are not native Germans, but all have been carefully coached to make the spoken and sung words clear and characterful.

Conductor Jacobs has a fine feel for the work. The tempos are all well chosen, with flexible adjustments at many points to reflect some shift in the action or wording. The Freiburg Baroque Orchestra provides many colors that we’ve rarely if ever heard before in this work, such as an enchantingly woodsy flute in the Hermit’s aria near the end of the work and slightly blaring horns in their many important entries. The important solo cello and viola passages in two arias are magnificently taken by Stefan Mühleisen and Corina Golomoz.

Ukrainian soprano Kateryna Kasper.

One personal objection: in a passage for the horns, a repeated appoggiatura is taken as short and before the beat. I find it annoying and obtrusive, especially when the tune is later repeated by chorus. But maybe I’ll get used to it and even grow fond of it. In any case, this is a recording I happily recommend to all opera lovers, or people who think they may become opera lovers!

No new recording of a major-repertory work can efface memories of the best parts of previous ones. If you want a recording that offers Weber’s opera as he himself authorized it (and as it has been performed for two centuries), I recommend that you follow the solid recommendation given again and again by record critics across the past sixty-plus years and get the Keilberth recording, whose three main singers are uniformly strong (Elisabeth Grümmer, Rudolph Schock, and Karl-Christian Kohn). Keilberth’s reading of the Wolf’s Glen Scene evokes the gruesomeness and horror more convincingly than does Jacobs’s. The opera’s music also flows better, because it is not interrupted by so much spoken commentary.

Or get the Carlos Kleiber recording, with a to-die-for Gundula Janowitz as Agathe; Peter Schreier and Theo Adam are very effective dramatically, though neither can match Janowitz’s glowing tones.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and is included here by kind permission.

Tagged: Carl Maria von Weber, Der Freischütz, Harmonia Mundi, Kateryna Kasper

The overture is, of course, a favorite if high school orchestra conductow. But, I did attend a performance of the opera until a few years ago in Karlsruhe. Kind of underwhelming, despite my German forebears.