Opera Album Review: Finally on CD — a Searing ’60s Opera from Russia about the Nazi Era

By Ralph P. Locke

Moissey Vainberg’s opera powerfully evokes the brutality of Hitler’s extermination camps and the moral ambiguity of postwar Germany.

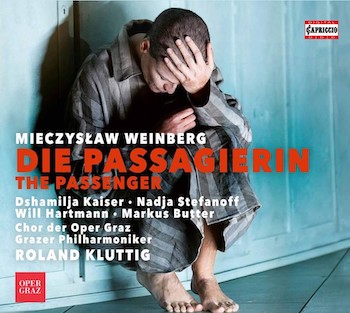

Moissei Vainberg (Mieczyslaw Vajnberg): The Passenger (1967-68)

Dshamilja Kaiser (Lisa), Nadja Stefanoff (Marta), Tetiana Miyus (Katja), Antonia Cosmina Stancu (Krystina), Will Hartmann (Walter), Markus Butter (Tadeusz).

Graz Opera Chorus and Philharmonic, cond. Roland Kluttig.

Capriccio 5455 [2 CDs] 156 minutes.

To purchase, click here.

Vainberg (or Weinberg or Vajnberg, 1919-1996) was a Jew born in Poland who lived most of his life in the Soviet Union. His first name, too, has variant spellings, including Mieczyslaw (in Polish) and Moissey (Yiddish, as adapted into Russian). His parents and sister were murdered by Nazi soldiers; his father-in-law, the renowned actor Solomon Mikhoels, was executed by Stalin’s thugs. Vainberg himself was imprisoned for a time, and he lived for decades thereafter under much stress and threat, as did his mentor and friend Shostakovich.

Vainberg’s music sometimes sounds like Dmitri Shostakovich, other times is harsher and more modernistic, indulging in brief dissonant excursions or borrowing from and commenting on a wide range of relatively familiar musical styles. The conductor of the present recording has offered in interview that Vainberg’s music often seems like a link between that of Shostakovich and that of Alfred Schnittke, but adds that it is also somewhat “discreet,” by which I think he means that it holds itself back from becoming hyper-emotional or self-indulgent. Dozens of Vainberg’s orchestral and chamber works have been praised in record magazines in recent years (especially his symphonies, quartets, and concertos). Vainberg also composed seven operas, one of which I reviewed in American Record Guide (“Mazel Tov!” or, in German, “Wir Gratulieren!”; January/February 2021), regretting that the performance bordered on the inept and used an unskillful German translation.

The Passenger (composed 1967-68) was the first of Vainberg’s operas, and it went unperformed during his lifetime, finally receiving a semi-staged performance in Moscow in 2006 and, four years later, a fully staged one, conducted by Teodor Currentzis, in Bregenz (Austria). I cannot determine from what I have read whether the original was entirely in Russian or whether certain characters sang in other languages, but the Bregenz production reworked the libretto such that the various characters use, at times, seven different languages: German and Polish (for the main German couple and the main Polish one), English (for conversations on board a transatlantic ocean liner), Russian, Czech, Yiddish, and French.

The opera got picked up by major and regional opera companies in Houston, Chicago, Miami, Madrid, Tel Aviv, and several cities in Germany and Austria, and, finally, in Yekaterinburg (Russia; this is the large city known during the Soviet decades as Sverdlovsk). Most often, I gather (though presumably not in Yekaterinburg), these productions have used the Bregenz adaptation, which of course works well in a modern opera house with a proficient supertitle system and an audience accustomed to relying on those projected words.

The opera’s title, in Russian, is Passazhirka; in German, Die Passagierin. Both mean The [Female] Passenger. The libretto was based on a 1959 Polish radio drama and 1962 novel, both by Zofia Posmysz-Piasecka, which also were the basis for Andrzej Munk’s 1963 film. The radio drama had a more precise title: The [Female] Passenger in Cabin 45. The plot takes place in alternating scenes: on a ship sailing to Buenos Aires circa 1960 and in the Auschwitz concentration camp two decades earlier. The scenes in the camp are viewed as if happening “below deck” but also “in memory.”

A scene from the Houston Grand Opera’s 2014 production of The Passenger/Passagierin.

A German woman, Lisa, is traveling by ocean liner with her husband Walter to his new diplomatic post in Buenos Aires. Act 1 includes the moment where Lisa tells her husband, for the first time, that she was a guard in Auschwitz. This is a powerful scene, in which she begs him to forgive her and love her still. She tries to excuse some of her behavior, while he expresses his fear that word of her shameful past will be snapped up by the news media and scupper his career.

Lisa sees another woman who, she fears, may be Marta, a Polish prisoner whom she supervised during her time as a guard at Auschwitz. From this point on, most of the rest of the opera occurs in flashback, in the camp. We see Lisa trying to do a favor for Marta in order to assuage her conscience and in hopes of being able to use Marta against the other inmates. Lisa offers Marta the chance to spend time with Tadeusz, a talented violinist who, she has learned, is Marta’s fiancé. But Tadeusz spurns the offer, not wanting to be beholden to Lisa.

Marta may have survived her incarceration and may be the woman that (now in “present time”) Lisa sees on the ship. Lisa has been dancing with Walter in the ship’s ballroom when she sees that the mysterious woman (the possible “Marta”) is asking the bandleader to strike up a certain waltz that had been the favorite of the Nazi commander at Auschwitz. The shock forces Lisa into another flashback set in the camp: the occasion when Tadeusz refused to play this very waltz and instead began Bach’s Chaconne in D Minor. The opera ends with a solo for Marta, recalling the friends she lost in the camp, including her beloved Tadeusz. Perhaps this soliloquy occurs after the camp is liberated; or perhaps we are in an alternate reality, hearing the thoughts of the late Marta coming to us from the Great Beyond.

There are numerous small but vivid roles, including women from Greece, Czechoslovakia, Poland, and Russia (hence the numerous languages in the Bregenz version). Two unnamed SS men engage in pointedly banal conversation mixed with an expressed wish that Germany speed up its elimination of undesirables. Depending on the production, additional characters (ship passengers, camp inmates) may move about, mingle, cower, observe, dance (on board ship), but not sing.

The music is full of character and contrast. There are numerous recurring themes, including strings of rising and descending “scales” using large intervals (whole tones, fourths, etc.), sometimes pushing the music into short stretches of polytonality reminding me of Britten (especially Peter Grimes). Vainberg often invokes various distinctive styles (e.g., mildly jazzy dance-band music for sociable scenes on the ocean liner) and specific pieces by other composers. The latter include Schubert’s famous “Marche Militaire” (a work whose long “afterlife” has been explored in a fascinating book by Scott Messing), the Viennese folk song “O, Du Lieber Augustin,” Shostakovich’s famous Waltz no. 2 in C minor (from the Suite for Variety Orchestra, a work sometimes erroneously called Suite for Jazz Orchestra No. 2), and, if my ears are not misleading me, the Russian folk song “Dark Eyes” (most extensively in a plaintive chorus near the end; the origin of this famous tune is much disputed) and Danilo’s song (from Lehár’s The Merry Widow) about going to Maxim’s restaurant. Perhaps Vainberg had in mind the allusions to the Lehár tune that Shostakovich drew on in the first movement of his Seventh Symphony to satirize the Nazi invaders. (Its use in Bartok’s Concerto for Orchestra is not, I think, being invoked here.)

The vocal lines are very conversational, sometimes quiet and quick with chamber-like accompaniment, sometimes grandly sustained at moments of great passion. An instance of the latter is when Lisa is shaken by the reappearance — or seeming reappearance — of Marta, whom she has presumed long dead. That triggers her sudden confession to her husband that she was a prison guard at Auschwitz.

The two main characters, Lisa and Marta, move in and out of the past. (That is, if the unknown woman really is Marta; perhaps Lisa’s guilty conscience is conjuring up the ghost of a woman who in fact was murdered along with millions of others.) At times a chorus that is either invisible or stands off to the side emphasizes the realities of life in the camp: “pitch-black wall of death, the last thing you saw before oblivion…” I found the work deeply absorbing, and was often able to hear the voices easily. Vainberg reserves heavy orchestration mainly for before or after a vocal statement, or for passages in which extensive stage action is carried out, such as when the camp inmates are being herded or beaten. Still, the frequent switching between various languages in the performance makes access to a printed libretto more necessary than in some operas.

A scene from the 2010 production of The Passenger/Passagierin, the Festspielhaus Bregenz.

The recording was made in February 2021 by a cast that had completed a run of nearly sold-out performances of the work before the pandemic began. The sound is beautifully clear and well balanced. The performance is alert and communicative on everybody’s part. The main singers, all new names to me, are a highly capable lot and less afflicted by wobble and bark than are many prominent opera singers nowadays. Some of the women in smaller roles make a particularly beautiful sound, such as Tetiana Miyus, who (as Katja) gets to sing a sad multistrophic Russian folk song unaccompanied (at a more flowing tempo than the glacial one used by her equivalent in the Bregenz production).

The booklet is inadequate and error-strewn. The best thing about it is that it includes the complete libretto. Alas, it is is given only in German and in English, even though more than half of the opera is here sung in Polish or other languages. The English rendering seems gauged to fit the contours of the vocal lines; it is credited to David Pountney (stage director of the Bregenz production) and the musicologist David Fanning. Unfortunately, the English libretto is riddled with errors: “warry,” “terrow,” “is remained,” “griming” (for “grinning”), “goo” (for “go”), “fust” (for “first”), and (twice) “prosecution” where the German original is “Verfolgung”: persecution. I suspect that a printed version of the Pountney-Fanning translation was fed through an optical-scanning machine, and nobody bothered to correct the inevitable mistranscriptions.

In the English version of the essay, important sentences are truncated, the meaning mangled. Also, the writer says that the opera contains some Hebrew. Actually, there’s a bit in Yiddish (sung by Hannah), which is of course a different language. (Yiddish is basically a version of German, though incorporating many Hebrew, Slavic, and Romance-language words. It is written in Hebrew characters, but it is not Hebrew.) We also aren’t told who made the seven-language translation (heard here) of the Russian libretto. Capriccio is a major label for classical music. It needs to ensure that its booklets are full and accurate.

The recording is also being released as a DVD. There have been two previous DVDs of the work; the conductors were Teodor Currentzis (at Bregenz) and Oliver von Dohnányi (at Yekaterinburg, Russia, a production done specifically for television). YouTube currently offers several videos, including one in which the video shows the score, page by page, rather than the singers (the audio track is of the Bregenz performance).

With this, its first appearance on compact disc, The Passenger further confirms its ongoing resonance for our age.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and is included here by kind permission.

Tagged: Capriccio, Graz Opera Chorus and Philharmonic, Holocaust, Moissey Vainberg, Ralph P. Locke, Roland Kluttig, Russian

It’s a gripping opera that doesn’t let you go if you are an empathetic person. I thought that it is the most representative work about the two sides of the evil that people do to others, the one of the perpetrators and the obe of the sufferers.

I’m glad to hear my favorable reaction echoed by a reader! I hope the new recording encourages people to get to know to this remarkable work–perhaps through any of the DVD versions of it.

–It also seems very effective theatrically. Opera-house and opera-studio directors, take notice!

[…] Opera Album Review: Finally on CD — a Searing ’60s Opera from Russia about the Nazi Era Moissey Vainberg’s opera powerfully evokes the brutality of Hitler’s extermination camps and the moral ambiguity of postwar Germany. artfuse.com […]