Television Review: “Ozark” — Nowhere to Go But Down

By Matt Hanson

Ozark supplied some vital, if depressing insights, about what liberal Americans really value: money and power, rather than what they say they treasure, family and equality. The catch is that this is no longer news.

Ozark, Netflix

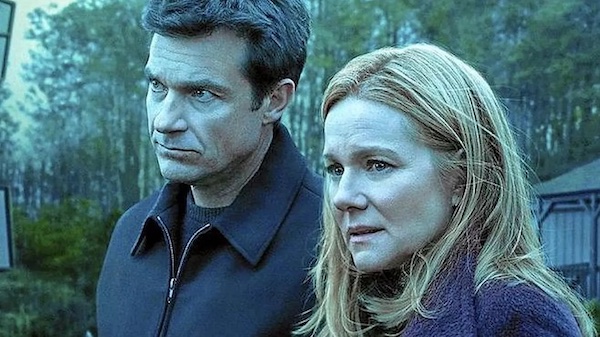

Jason Bateman and Laura Linney In Ozark

Ozark, whose final season recently aired on Netflix, is a part of a larger trend of edgy, dramatic TV that explores, either overtly or subtly, the moral rot generated by raw capitalism. The Wire trenchantly dramatized the blood sport waged by marginalized communities struggling to survive by any means necessary. The Sopranos made viewers self-consciously root for an amoral if charismatic gangster hero. Breaking Bad celebrated, via black comedy, how an initially meek nerd could live the American dream – by becoming a drug kingpin. Succession depicts how bottomless privilege inevitably gives birth to monsters. At its best, Ozark came within shouting distance of those shows’ dramatic force, yet its rushed ending, limited characterizations, and weak conclusion ultimately held it back from nailing its targets.

The series centers on Marty and Wendy Byrde, a married middle class couple from suburban Chicago with two teenage children. The family finds itself (somewhat implausibly) having to launder drug money for a Mexican cartel in the titular area of central Missouri. Jason Bateman’s Marty Byrde is an ace accountant who is too emotionally repressed to rein in his passive-aggressive and increasingly maniacal wife, Wendy, played superbly by Laura Linney. Bateman does a fine job of conveying hubbie’s limited emotional range, but he is trapped in a script that gives him little more to do than mumble and furrow his brow.

As the Byrdes become ever more corrupt, ruthless, and powerful, Linney takes her self-satisfied white suburban mom (aka a “Karen”) deeper into maniacal, Lady Macbeth territory. She wants to tell herself and anyone who will listen that everything’s always fine and that she’s really just looking out for her family. She goads an easily-convinced Marty into increasingly desperate schemes that put them all in danger. The end result of the liberal damage control to erode whatever parental moral high ground Wendy assumes she stands on. At one point, the good left-winger who worked for Obama (before he was a star) casually defends her decisions by asserting the (unpleasant but often true) fact that in America no one cares what you did to get your money.

This suburban Machiavellian mentality initially collides with the opportunistic spirit of the Langmores. These Ozark locals are every bit as grasping as the Byrdes, but they lack the ready capital and comfortable social status that comes with membership in the middle class. The show’s most interesting character by far is Ruth Langmore, a teenage miscreant who gradually becomes a major player in the Byrde’s criminal enterprise. Julia Garner plays scrawny, perpetually scowling Ruth with just the right blend of untapped ambition and seething intelligence.

Ruth dearly loves her roughneck family while knowing full well that she hasn’t been dealt the favorable class cards the smug Byrdes enjoy. Respectable credentials would have provided her with the opportunity to do something other than commit small-time crime in a humid Midwestern beach town that is going nowhere fast. We feel for Ruth, not because she’s written to ask for our sympathy, but because the deck has been so powerfully stacked against her. She is the figure of the underdog tenaciously screwing her growing courage to the sticking place. Ruth is hustling to go as far as she possibly can in a lopsided economic landscape — of course, no matter how far she struggles upward, she will inevitably slide downward.

Ozark is at its best when it presents this kind of searing class analysis. Upward mobility has become an neo-liberal fairy tale for the few who can break through forbiddingly high barriers to success. The dramaturgical problem with the series is that, once it established how its various characters fit into their respective places within their brutally inequitable environment, there is is no room left for transformation or surprise. “It is what it is,” as cynics say; characters’ arcs tend to flatline. Yes, the show perceptively puts the screws to the glossy ruthlessness of suburbia, probes behind the shiny veneer of so-called “real America.” But we are stuck in a world where everyone is either already terrible or heading there fast. There are few moments of suspense or dramatic tension. The ancient argument about tragedy is that the hero’s fatal flaw deepens our compassion for their doomed plight because we recognize it as our own. In terms of dramatic challenge, it is helpful to have a character who begins as an innocent and gradually becomes corrupted — or the other way around. Even better, see the triumph of corruption through the eyes of an innocent, such as the child in William Faulkner’s brilliant short story “Barn Burning.” Ozark doesn’t have many characters, other than (arguably) Ruth, who aren’t crooked from the get-go. These figures have no flaws or vulnerabilities that draw our compassion. In the final season it’s clear that Ruth is the only one with a semblance of a redeeming feature. And this doth not a compelling show make.

I’ll keep this review spoiler-free, though the final few episodes are marred by the writers trying to hurriedly pack too much plot into a very condensed period of time. New characters are introduced quickly with scant backstory — and they prove to be essential to the narrative. This is a sure sign that a series is speedily running out of gas. As the Byrdes finally settle into becoming the public oligarchs they have always wanted to be, viewers are expected to be shaken up by the sudden reversal of one of the characters. Some commenters have argued (correctly, in my view) that there isn’t enough buildup in the script for that crucial moment to resonate in a dramatically effective way.

Ozark supplied some vital, if depressing insights, about what liberal Americans really value: money and power, rather than what they say they treasure, family and equality. The catch is that that this is no longer news. What is needed now is more dynamic characters, more nuanced class analysis, and at least glimpses of a significant opposition. Did anyone really care about the Byrdes denouement? I’m already starting to forget them.

Matt Hanson is a contributing editor at the Arts Fuse whose work has also appeared in American Interest, Baffler, Guardian, Millions, New Yorker, Smart Set, and elsewhere. A longtime resident of Boston, he now lives in New Orleans.

“Ozark supplied some vital, if depressing insights, about what liberal Americans really value: money and power,”

Seriously? Libs value money and power? That’s a mighty broad brush to paint with, fella. Who are you, and who thought it was a good idea to publish you? And as a side note, the Ozarks are in the deep south of Missouri, not central Missouri.

“Libs value power and money “ – spot on.

Power and money is valued by people across the ideological spectrum … it is as American as apple pie.