May Short Fuses – Materia Critica

Each month, our arts critics — music, book, theater, dance, television, film, and visual arts — fire off a few brief reviews.

Jazz

Rich in love songs, Marco Pignataro’s Awakening is both modern and romantic.

Saxophonist Marco Pignataro has served as managing director of the Berklee Global Jazz Institute at Berklee College of Music in Boston since 2009. For Awakening, his just-released second recording for Zoho Music, he has assembled a multi-generational, multi-ethnic, multi-gender group of Berklee colleagues: venerable pianist Kenny Werner, singer-guitarist Nadia Washington, and bassist Devon Gates. Werner and Gates also provide backing vocals, while Pignataro’s arsenal includes soprano, alto, and tenor saxes.

Saxophonist Marco Pignataro has served as managing director of the Berklee Global Jazz Institute at Berklee College of Music in Boston since 2009. For Awakening, his just-released second recording for Zoho Music, he has assembled a multi-generational, multi-ethnic, multi-gender group of Berklee colleagues: venerable pianist Kenny Werner, singer-guitarist Nadia Washington, and bassist Devon Gates. Werner and Gates also provide backing vocals, while Pignataro’s arsenal includes soprano, alto, and tenor saxes.

The CD’s 12 tracks include covers of a diverse selection of pop songs from the 1960 and 1970s: Stevie Wonder’s “Send One Your Love,” Ben E. King’s “Stand By Me”, Gilbert O’Sullivan’s “Alone Again Naturally,” and the Beatles’ “Because.” The rest are originals by Pignataro and Werner, the “lyrics” of which are poems by Pignataro spoken by Washington, whose voice is as expressive speaking as it is singing.

The recording itself is from a virtual live concert held at WGBH’s Fraser Studio in July 2021, an event sponsored by JazzBoston. Rich in love songs, the album is both modern and romantic. And while there is plenty of singing — Washington bringing a surprising degree of hipness and style to the melodramatic O’Sullivan tune is a highlight—according to Pignataro, “I want to return to the old tradition of ‘singing’ beautiful melodies through the horn, as master story tellers such as Lester Young and Stan Getz did.”

The music is soothing and gentle on the ears, a good soundtrack to a candlelight dinner, yet not at all soporific. Pignataro and Werner are both exceptional soloists — as on the saxophonist’s “Farfallina” (Italian for “little butterfly”) — and Gates’ well-articulated acoustic bass is always muscling the music forward. Washington’s deft acoustic guitar playing throughout adds appealing texture to the group’s sound, and she and Gates harmonize beautifully on “Because.”

— Jason M. Rubin

Books

Not the most exciting read really, but I must admit that Queen: As It Began is impressively thorough.

First published in 1992, Queen: As It Began was the go-to book on their royal highnesses for nearly 20 years, until Mark Blake’s Is This the Real Life?: The Untold Story of Queen came along and stole the distinction in 2010.

First published in 1992, Queen: As It Began was the go-to book on their royal highnesses for nearly 20 years, until Mark Blake’s Is This the Real Life?: The Untold Story of Queen came along and stole the distinction in 2010.

Now, thirty years after initial publication, Jacky Smith and Jim Jenkins have returned with an “authorized and revised” edition of their tome and Is This the Real Life? remains the champion.

Blake’s book is filled with color and context. On the other hand, Smith (head of the Queen International Fan Club for 40 years) and Jenkins (Queen super fan and liner note scribe) supply a dry and not at all artful telling of the band’s career; just paragraph after paragraph of “On this date Queen did this, on that date Queen did that, at a latter date Queen did another thing.”

Not the most exciting read really, but I must admit that Queen: As It Began is impressively thorough. I quickly lost track of how many times I stumbled upon some interesting Queen factoid, asked myself, “Wait, did I know that?” and then thumbed through my ‘92 edition only to find that the tidbit was in that version too, I’d just forgotten about it. If any other Queen biography (including Blake’s) included these morsels, I missed them. So, while a casual fan might not care one way or the other, as a completist I was ultimately won over. In the end, As It Began won’t win any prizes for poetry, but I tip my cap to how much information it packs into its prose.

— Adam Ellsworth

It is as if these brief tales were composed yesterday, and they will be as stunning tomorrow as they were in 1939, the year their author, Chana Blankshteyn, died.

It is always a thrill for me to recognize the scope of an artist a smattering of whose work I have read only in niche, Jewish journals. I experienced that thrill with Fear and Other Stories (Wayne State University Press), a collection of nine short stories by the Yiddish writer Chana Blankshteyn.I have not read them in the original, so I must rely on translator Anita Norich, trusting that the modernist, even post modernist, mode of expression in English accurately conveys Blankshteyn’s Yiddish. Both language and tone impress. It is as if these brief tales were composed yesterday, and they will be as stunning tomorrow as they were in 1939, the year Blankshteyn died. Notably: just before the Nazi invasion of Poland, and the horrors of war became evident worldwide. These tales, therefore, are not reflections on that tragedy, but rather detail daily moments in prewar Europe: Vilnius, Paris, a railroad station, a courtyard. The foreboding here is more internal and social than it is political. Grand tragedy is unimaginable. In fact, blurred visions of the possibility of love, or at least comfort, prevail.

Chana Blankshteyn (b: 1860? Anna/Anyuta Shur) was well known in her lifetime. The youngest child of a well-to-do Lithuanian Jewish family, she was tutored by French and German governesses, bore two children and was twice divorced. After leaving her wealthy diamond merchant second husband, she served as a nurse in St Petersburg in the Russian army, returning impoverished to Vilnius in 1920. Only then did she take up her pen and write in Yiddish, a language she mastered in her fifties and sixties in order to work for political causes among the Jewish minority of her native city. Blankshteyn first ran for office in the Yiddish People’s Party, arguing for linguistic/cultural Yiddish identity as the language of European Jews in every country where they lived. She later joined the Poaley Tsiyom, a group committed to socialist ideals in Europe and in establishing a Yiddish presence in Palestine. She created the Vilna Women’s Association, and as publisher, editor, journalist, and fabulist continually championed equality for women in both intimate and public life.

Chana Blankshteyn (b: 1860? Anna/Anyuta Shur) was well known in her lifetime. The youngest child of a well-to-do Lithuanian Jewish family, she was tutored by French and German governesses, bore two children and was twice divorced. After leaving her wealthy diamond merchant second husband, she served as a nurse in St Petersburg in the Russian army, returning impoverished to Vilnius in 1920. Only then did she take up her pen and write in Yiddish, a language she mastered in her fifties and sixties in order to work for political causes among the Jewish minority of her native city. Blankshteyn first ran for office in the Yiddish People’s Party, arguing for linguistic/cultural Yiddish identity as the language of European Jews in every country where they lived. She later joined the Poaley Tsiyom, a group committed to socialist ideals in Europe and in establishing a Yiddish presence in Palestine. She created the Vilna Women’s Association, and as publisher, editor, journalist, and fabulist continually championed equality for women in both intimate and public life.

Now for these tales themselves: The title story, “Fear,” creates an eerie aura at a train station. Who has not worried about missing a connection? The atmosphere is Kafkaesque: death is possible, time is essential,yet uncontrollable. Sentences are fragmented, like moments. “Do Not Punish” supplies a different early nineteenth century feel. Given the tale’s niceties of manners (although Norich hiccups and commits a grammatical infelicity) and the formality of its fairy-tale-like causation, Blanksheyn might almost be a half sister Grimm. “The First Hand” is Dickensian in its moves from the grime of an orphanage to the darkness of upper class life: “things aren’t always happy even among the rich” we are reminded. We are aware of pogrom in this canvas, which is more expansive — in terms of geography, time, and social class — than the other stories here. Despite the translator’s rare choice of a cliche (‘ample bosom’ – twice), the shifting moods and settings feel authentic. After the initial economic and personal tensions, the elegant simplicity of the ending offers the reader a comforting exhalation.

“The Decree” brings us into Hasidic homes. Their inhabitants are building up their resistance to encroaching secular communism and the venom of anti-semitism. We are introduced to the ironically amusing appellation: Comrade Rabbi. “Director Vulman” draws the reader into a sugar factory where we encounter a bewildered but dangerous manager: “the cruel, dreadful soul, that lived in people when humanity just emerged from the Stone Age, that same cruel soul lives in the modern gentleman, he who conquered the earth and the air. Sweating and struggling, man constantly builds new treasures only to destroy them in blind fury driven by hunger and thirst, seeking a bit of joy…..” Murder and cool mornings clash chillingly. “Who” serves up cunning shifts of tense and point of view “where are the borders between superstition and what we only believe is superstition” reveal the ravages of the afterlife of the First World War. Shifting points of view occur again in “An Incident,” which contains moving gender drama. For me, the only unsuccessful tale is “Colleague Sheyndele” in which the personification of various nature images comes off as amateurish and contrived.

But the closing story, “Our Courtyard,” is a masterful conclusion to this selection of stories. The tale is told through the first person by a female narrator. At first, she is watching through a window, then she is sleigh riding past cottages and their courtyards. We are voyeurs in partnership with Blankshteyn’s narrator in a world which now has vanished. Time also passes in this eight-part tale. “It is raining a little and the broken red bricks on the wall look like dried blood.” And perhaps they are.

Note: Another revival of a forgotten Yiddish woman writer of short stories is now available: Blume Lemuel’s Oedipus in Brooklyn (Mandel Vilar Press). A new translation, beautifully rendered from the Yiddish by Ellen Cassidy and Yermiyahu Ahron Taub.

— Joann Green Breuer

As the Russian invasion of Ukraine rolls on, Ukrainians led by a Jewish President resist, and hundreds are deported to Russia, it is instructive to read Yelena and Galina Lembersky’s new memoir Like a Drop of Ink in a Downpour Memoirs of Soviet Russia (Cherry Orchard Books, 257 pp). Galina is the daughter and Yelena the grand-daughter of Felix Lembersky, the prominent Soviet Jewish artist whose name evokes Lemberg, aka Lvov, aka Lviv. They and Yelena’s grandmother emigrated from Leningrad to Ann Arbor, Michigan in the ’80s, spurred by the goal of preserving Lembersky’s work. This story about life in the Soviet Union is a valuable partly because it is not about prominent refuseniks or about the Russian gulags or about the Second World War. This is a close-up look at what ordinary postwar existence was like for Jewish citizens of the USSR.

As the Russian invasion of Ukraine rolls on, Ukrainians led by a Jewish President resist, and hundreds are deported to Russia, it is instructive to read Yelena and Galina Lembersky’s new memoir Like a Drop of Ink in a Downpour Memoirs of Soviet Russia (Cherry Orchard Books, 257 pp). Galina is the daughter and Yelena the grand-daughter of Felix Lembersky, the prominent Soviet Jewish artist whose name evokes Lemberg, aka Lvov, aka Lviv. They and Yelena’s grandmother emigrated from Leningrad to Ann Arbor, Michigan in the ’80s, spurred by the goal of preserving Lembersky’s work. This story about life in the Soviet Union is a valuable partly because it is not about prominent refuseniks or about the Russian gulags or about the Second World War. This is a close-up look at what ordinary postwar existence was like for Jewish citizens of the USSR.

On the hyper-saturated memoir shelf this approach to the Soviet Union is under-represented. From my point of view, the authors are descendants of Holocaust survivors. But to just identify themselves as Jewish was difficult and often dangerous – “At my home the word Jew is said with empathy and in a hushed voice, though no one explains to me why,” writes Yelena. Though the Holocaust has become a household word in the U.S., the Soviet Union did not use or even recognize the term, so the Lemberskys, like so may other Soviet Jews, have no consciousness of themselves as belonging to a larger group.

The pair’s narrative — divided into sections by Yelena and Galina — is compelling and parts are beautifully written. Like a Drop of Ink in a Downpour provides an unusual glimpse into the world of Soviet citizens which has been more frequently described by men. I was particularly struck by the long-term consequences of casual decisions and the bravery of ordinary people — strangers as well as friends. The book raises thorny issues of family loyalty, the importance of artists and art, and the many aspects of individual agency that Americans take for granted.

— Helen Epstein has been a reviewer for the Fuse since its inception. Her latest book is Getting Through It: My Year of Cancer During Covid.

Critic Jed Perl’s argument is that all artists inevitably reckon with the possibilities offered by tradition.

Alarmed at the rise of cultural and social forces that are minimizing the freestanding power of the arts by labeling them “radical, conservative, liberal, gay, straight, feminist, Black or white,” veteran art critic Jed Perl takes on what he labels “the stranglehold of relevance” in his disappointingly slim polemic Authority and Freedom: A Defense of the Arts (Knopf, 161 pp, $20). He has set out to articulate the independent value of art at a time in which he believes it is being opportunistically brushed aside. He wants to make a case for why, at this time of political, social, and environmental challenge, we must understand that “art is a realm of its own — a realm that touches and affects us … but remains a world apart.”And that independent realm is built on the premise that “no matter how the world encroaches on the artist, the artist in the act of creation must stand firm in the knowledge that art has its own laws and logic. These are the fundamentals of the creative vocation.” Following that lonely vocation is an act of courage, mistaken today by too many as “a retreat into self-absorption and narcissism.”

Alarmed at the rise of cultural and social forces that are minimizing the freestanding power of the arts by labeling them “radical, conservative, liberal, gay, straight, feminist, Black or white,” veteran art critic Jed Perl takes on what he labels “the stranglehold of relevance” in his disappointingly slim polemic Authority and Freedom: A Defense of the Arts (Knopf, 161 pp, $20). He has set out to articulate the independent value of art at a time in which he believes it is being opportunistically brushed aside. He wants to make a case for why, at this time of political, social, and environmental challenge, we must understand that “art is a realm of its own — a realm that touches and affects us … but remains a world apart.”And that independent realm is built on the premise that “no matter how the world encroaches on the artist, the artist in the act of creation must stand firm in the knowledge that art has its own laws and logic. These are the fundamentals of the creative vocation.” Following that lonely vocation is an act of courage, mistaken today by too many as “a retreat into self-absorption and narcissism.”

Perl’s argument is that all artists inevitably reckon with the possibilities offered by tradition. The freedom of the imagination depends on maintaining a respectful tension with authority; creative acts of personal rebellion are free to be either extreme or modest. “The artist must engage with the freedom that’s possible within the tradition, so that making becomes an exploration of how things have been made in the past,” Perl insists. Unfortunately, the critic’s many proclamations about the transcendence of art comes off as tidy boilerplate: “The artistic struggle is personal and impersonal and particular and universal. The work of art, with its freestanding power, is the resolution of that struggle.” Is that struggle ever completely resolved? Or is it dynamic? As William Blake puts it, “Without contraries is no progression.” Perl doesn’t test his ideas terribly hard. He takes the easy way out, ignoring thinkers and artists whose approaches strongly contest his — the examples he draws on, from Picasso’s Guernica and the singing of Aretha Franklin to the theorizing of Leon Trotsky, make up a fairly small garden of cherry-picked evidence.

In addition, his weak consideration of popular culture is a tell. Perl’s description of the rich experience of reading the novels of Jane Austen could easily be applied to the lovers of Marvel superhero movies. These admirers tirelessly explicate every detail, treasure every nuance, speculate about character motivation, dissect every frame, and analyze how each film elaborates on the ongoing vision of the comic book series. Perhaps passionate engagement with art may be more limited, in terms of articulating its value, than Perl admits. A cultural dilemma the book doesn’t address but should, given Perl’s interest in talking about the primal attraction of art, is the growing confusion between critic and fan.

I am sympathetic to Perl’s position, but the duality he is addressing is not so much authority and freedom but art for art’s sake and art’s responsibility to reflect brutal existential reality. Perl prefers art for art’s sake, which is fine. But at one point he also suggests that the artist, in the words of Isaiah Berlin, “is free to fulfill one’s wishes … if one understands the nature of the world in which one lives; if this world has a pattern and purpose, to ignore this central fact is to court disaster.” But later Perl draws on a poem by W.H. Auden as a means to undercut the notion that an artist should strive for a “profound understanding of the age in which he lives.” Auden dismisses this duty as simply “filling up of a social quiz.” But understanding the world we are creating is important. Artists can ignore ideology — but not physics. In a few decades, the climate crisis will be growing even more destructively acute than it is now. The degradation of nature will continue and it will continue to change the planet forever. Life will be increasingly miserable for millions and millions because of rising temperatures, lack of potable water, the disappearance of insects and animals, and the violent political turmoil triggered by mass migration. The “pattern and purpose” of what we are doing to nature and ourselves is unbearably clear. Of course, artists are free to fail that “social quiz” — at their peril.

— Bill Marx

Visual Arts

Happy Birthday Frederick Law Olmsted!

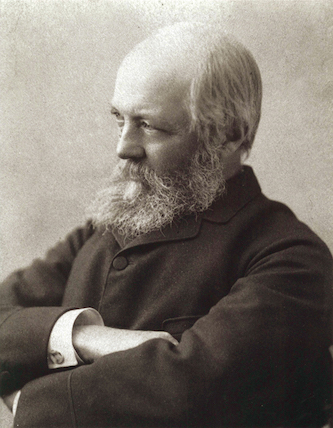

Portrait of Frederick Law Olmstead in later years. Photo: courtesy of National Association for Olmsted Parks.

This year, 2022, marks the 200th birthday of the founding father of landscape architecture, Frederick Law Olmsted, who was born on April 26,1822. We are especially touched by his genius in the Boston area with his Emerald Necklace, though he played a role in the design of many other of our nation’s beloved parks and public spaces.

Olmsted’s legacy can be studied and admired at Fairsted (a National Park Service site), his home and studio in Brookline, MA. His influence can easily be seen driving west on Beacon Street from Boston into Brookline where he deftly placed a lush tree canopy. With the last two years or so of the Covid plague, his creative touch has been shown to be more essential than ever. Our outdoor venues served as rare oases for near normal walks.

Olmsted’s visionary philosophy regarding a shared public landscape was about enhancing freedom, human connection, and public health. Olmsted accomplished these goals through the imaginative manipulation of terrain, plants, and water. This farsightedness is as essential today as it was over 150 years ago, when he completed his first major collaboration — New York City’s Central Park.

Perhaps Olmsted had been touched by a muse when he visited England’s Birkenhead Park in 1850. He was not only charmed by his experience; he was inspired by the liberality of its beauties, how they benefited all who entered. This democratic impulse became a major influence in his own approach: a park should have no social or economic barriers. Parks were common grounds that served a medicinal purpose. For Olmsted, parks served as indispensable antidotes to the mounting chaos and rush of urban life.

Born the son of a Connecticut merchant, Olmsted was a two-time Yale dropout, a failed farmer, a short-time seaman, and a thoughtful journalist who wrote seriously about slavery in the American South. His experiences informed his genius.

During our recent dark period of pandemic lockdown, Olmsted’s parks were more than invaluable contributions to our cultural and environmental heritage. His belief that parks serve as centers of restoration and recreation, as expressions of civility and health, contributed to our sense of living in a shared place, a belief that nurtures the collective welfare. This year, we celebrate Olmsted’s contribution to our collective well-being, our individual happiness, and our appreciation of the natural. Happy Birthday FLO!

— Mark Favermann

Classical Music

Despite the brevity of the selections – both Sinfonias, played back-to-back, only run about twenty minutes – these releases make an excellent introduction to George Walker’s wider body of work.

Composer George Walker — his writing is inherently lyrical.

While George Walker wasn’t exactly a neglected voice during his long life – he died at ninety-six in 2018 and was recognized with a Pulitzer Prize for his Lyric for Strings in 1996 – he’s still benefiting from the recent focus on the creative work of Black American composers. Most recently, the National Symphony Orchestra (NSO) announced that all five of Walker’s Sinfonias, written between 1984 and 2016, would be released on their in-house label. The first two installments (of Sinfonias Nos. 1 and 4) are out now.

Both pieces share a certain toughness of character, with angular melodies and sharply-defined rhythmic figures predominating. However, Walker’s writing is inherently lyrical: the First Sinfonia’s opening movement is unfailingly mellifluous, as is the whole of No. 4 (which is based on the spirituals “Roll, Jordan, Roll” and “There is a Balm in Gilead”).

His ear for sonority is likewise impressive. Suffice it to say, the orchestra is knowingly utilized in both pieces: there’s a precision to the instrumentation that recalls Copland, especially, for its clarity and resonance.

And there’s personality to go around. If No. 1 is a bit edgier in tone and more harmonically pungent, the Fourth offers an ingratiating blend of devotion (perhaps held over from those spirituals) and dancing playfulness.

The NSO’s performances, led by music director Gianandrea Noseda, are vibrant. Suffice it to say, the orchestra sounds perfectly at home in this repertoire. Despite the brevity of the selections – both Sinfonias, played back-to-back, only run about twenty minutes – these releases make an excellent introduction to Walker’s wider body of work.

Given what else is out there, then – especially Andris Nelsons’ and Leonard Bernstein’s recordings of this piece – and we’ve got a “Leningrad” that just comes up short.

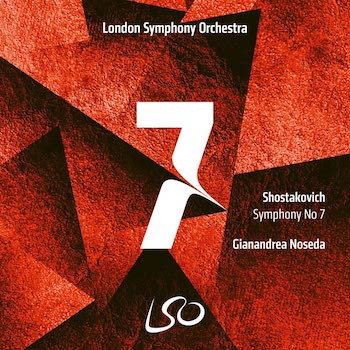

Meanwhile, across the Pond, Gianandrea Noseda’s Shostakovich cycle with the London Symphony Orchestra (LSO) continues with this traversal of the “Leningrad” Symphony (No. 7).

Meanwhile, across the Pond, Gianandrea Noseda’s Shostakovich cycle with the London Symphony Orchestra (LSO) continues with this traversal of the “Leningrad” Symphony (No. 7).

Previous installments in this series have been, interpretively, hit-or-miss. Given the competition – recent cycles from Mark Wigglesworth and Vasily Petrenko; the Boston Symphony’s almost-finished one with Andris Nelsons; as well as benchmarks from Bernard Haitink, Rudolf Barshai, Kirill Kondrashin, Vladimir Ashkenazy, and others – that’s problematic. While this “Leningrad” gets several things right, it occasionally misses the mark.

As far as the former goes, tempos move smartly, balances are excellent, and the LSO plays with color.

The first two movements unfold flawlessly. In the opener, Noseda’s no-nonsense approach to the big march theme allows the music to speak furiously at its climax. Transitions, too, are nicely focused and the roundness of the LSO’s playing in lyrical spots makes a wonderful contrast to their more muscular interjections elsewhere.

Much the same goes for the second movement, which is crisply articulated, its melodies beautifully accompanied (just listen to the bass clarinet solo with flutes near movement’s end).

Alas, the third movement is too fast: Noseda ignores the metronome markings in the Largo and Adagio sections and, as a result, when the big, crunching climaxes come, they lack weight. The reading also requires mightier contrasts of dynamics and, at times, intensity: the first violin’s recurring recitatives want for fervency.

In the finale, good tempos and crisp ostinato figures culminate in a whipping storm, though the bridge into the final peroration lacks a needed degree or two of intensity. Partly as a result, the closing bars ring hollow.

Given what else is out there, then – especially Nelsons’ and Leonard Bernstein’s recordings of this piece – and we’ve got a “Leningrad” that just comes up short.

— Jonathan Blumhofer

Tagged: Adam Ellsworth, Chana Blankshteyn, Fear and Other Stories, George Walker, Gianandrea Noseda, Jacky Smith, Jason M. Rubin, Jim Jenkins, Joann Green Breuer, Jonathan Blumhofer, London-Symphony-Orchestra, Marco Pignataro, Mark Favermann, Queen: As It Began

This is an epigraph in Caio Fernando Abreu’s short story collection Moldy Strawberries (archipelago books) and thought it a concise riposte to Perl’s argument:

Osman Lins, Unwitnessed War