Book Review: “Every Good Boy Does Fine” — A Career in Music, Elucidated With Brilliance

By Stephen Provizer

Pianist Jeremy Denk is a sensitive and articulate polymath who can elucidate his ideas about music with wit, humor, and style.

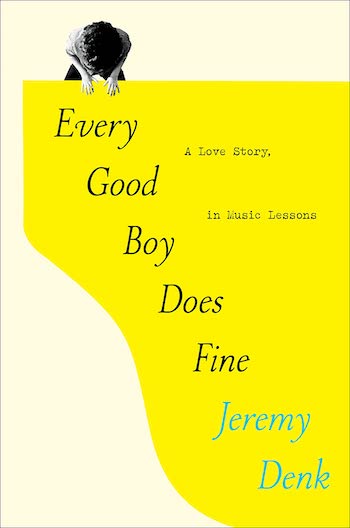

Every Good Boy Does Fine: A Love Story, in Music Lessons by Jeremy Denk. Penguin Random House, 384 pages, $28.99.

During the 1950s-1960s, Leonard Bernstein was the “face” of classical music in American popular culture. He was a pianist, conductor, and composer with a charismatic personality who served as a comfortable bridge between the masses and classical music via his televised Young People’s Concerts. Pianist Jeremy Denk occupies a similar spot in 21st-century American musical culture. A top-tier pianist, he is also a popular blogger, a YouTube presence, and a frequent guest on television and radio shows. He is also an intensely creative thinker and his new volume, Every Good Boy Does Fine, is far more than an autobiography. In fact, it is the finest volume of its ambitious type that I’ve ever encountered.

Part of me wants to simply write: read this book. However, I realize that my credibility, though considerable given that I am an Arts Fuse critic, does not have much sway on book sales, so some convincing exegesis is necessary. Quotations from Denk will do most of the heavy lifting.

The book is structured chronologically. Most of the narrative relates to his life as an aspiring pianist, juxtaposed with stories of his difficult relationship with his family, especially with his father. Precious little of the outside world intrudes. Initially that is a little disconcerting, but I accepted it as appropriate given the extreme insularity of the world Denk inhabits. He also talks, albeit sparingly, about his romantic life — his partners are presented as ciphers. Given the depth that he brings to his looks at his own psychology and that of his teachers, I found this somewhat unsatisfying, but again, it does not undermine the power of the narrative. For example, he is fairly unsparing in his analysis of his own immaturity. One of his teachers tries to get him to respect rests and not rush through them: “He was right, of course; my urge was to connect, always to connect. Like someone who won’t stop talking, who won’t let anyone else speak, or even take a moment to breathe.”

After hearing his superb playing, I was anxious to read his thoughts about music — and analysis of music is an important part of Every Good Boy Does Fine. He does this brilliantly — he has a rare capacity to explain melody, harmony, and rhythm in ways that are sophisticated yet clear. Musicians as well as nonmusicians will find his ideas illuminating. The key is how Denk uses humor and metaphor to tie his descriptions to everyday experience. Here he is talking about a high school conductor: ”I can see her lifting her baton to get us started, like someone raising an arm to avert a blow from a blunt object, and then we would all come thumping in with our lazy rhythms, as if Bach had composed the piece for a parade of retired sumo wrestlers.”

Denk’s insights into the music of composers whose repertoire he concentrates on — especially Bach, Mozart, Brahms, Beethoven — are rich. Again, he expresses his musical insights in ways readers with or without musical experience can understand. On Beethoven’s use of melody: “At this juncture, Beethoven puts us in touch with one of melody’s central contradictions. On the one hand, melody’s desire to be memorable, repeatable, like a keepsake or beloved photo. On the other, a native ability, and a desperate need, to transform. Melody (Beethoven reminds us) keeps switching between noun and verb; being and becoming.”

Denk is equally memorable about rhythm in Beethoven:

When I play this [Beethoven Sonata for Cello and Piano in D Major], I bow and smile, knowing my official work is over, but I can’t help feeling that the final downbeat has not yet arrived. It needs to exist, and refuses to exist, and you may feel the elusive arrival in your soul during the fading applause, or hours or days later, or maybe it won’t come at all and you’ll have to go back to the practice room to figure out your concept of rhythm all over again, but in the meantime — and I think this is what Beethoven was after all along, an epiphany you can’t fit in the program notes or the preconcert lecture — it feels so fucking good to be alive. In that play of rhythm and time, death, so inescapable just one movement earlier, is nowhere to be found.

Why does Brahms unexpectedly leave out a note in a series?

One skipped tone — no big deal. You might say I’m making a mountain out of a molehill: a cutting and fitting indictment, if it weren’t for the fact that melody is the greatest device ever invented for converting mountains into molehills. It’s a stage where details are destined to become momentous … the gap he’s created must be addressed … meanwhile it tugs at my heart. I feel the need created by the act of skipping over — the sense of a loss in the line, the pleasure of filling it in and completing the past. It mirrors so many moments and patterns of so-called real life.

Pianist Jeremy Denk. Photo: Michael Wilson

The fact that he writes the expression “so-called real life” is telling. From an early age, Denk’s love of music was profound. But one also senses that when he was younger he embraced the life in music so strongly because, as he admits, he was not especially good at life itself (first kiss at the age of 17). Few of us are prodigies, but any musician — or anyone who struggles to attain mastery over anything — can identify with Denk’s flip-flopping between insecurity and over-the-top responses to praise. By the end of the book, this see-sawing seems to have more or less dissipated, but the path to confidence was torturous. Much of the book is given over to describing the intensely pressurized environment of his piano studies.

Denk’s analysis of his lessons includes consideration of music’s technical aspects — but he goes well beyond that:

As at all my … lessons, no matter how scolded and seared, I still felt I was playing the piano in my bubble, doing my things, and there was dignity to that, even in failure. But Norman wouldn’t let me have my bubble. His teaching required me to give up my dignity, as the price of something better.

The pianist bonded most deeply — and had his most satisfying student-teacher relationship — with Hungarian pianist Gyorgy Sebok, his instructor at Indiana University. “He [Sebok] kept alternating between spirit guide and physics teacher, trying to bridge the gap between boring technical detail and the mysteries of the universe.”

This description reflects the polarities that Denk deftly balances in this superb book. He is a sensitive and articulate polymath who can elucidate ideas with wit, humor, and style. Because, for him, the line between music and life is so permeable, what he has to say is as revealing about life as it is about music. His is a rare talent.

Stephen Provizer writes on a range of subjects, most often the arts. He is a musician and blogs about jazz here.

Tagged: Every Good Boy Does Fine, Jeremy Denk, Stephen Provizer

Thanks for your email reminding me to support Arts Fuse.

You totally had me at Denk’s beautiful description of Beethoven’s use of melody.

I do think that you and other critics have sway on book sales, by the way. I, for one, will read this book with pleasure!