Poetry Review: “Time Is a Mother” – Grieving through Language

By Henry Chandonnet

Ocean Vuong’s new collection of poetry is a dazzling investigation of love and loss, inspiring both nostalgia and release.

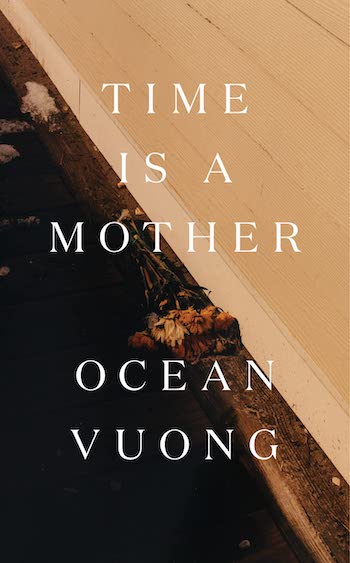

Time Is a Mother by Ocean Vuong. Penguin Press, 114 pages, $24.

Death and art go hand-in-hand. In fact, loss has often inspired enormous creative innovation. Still, meditations on death can be somewhat one-note, forcing the reader to experience, over and over, the all-consuming sadness that comes from grieving. In his newest collection of poetry, Time Is a Mother, Ocean Vuong masterfully eludes this obstacle. The poet’s language recognizes the trauma of death, but also revels in the glory of life . In this book, Vuong grieves the loss of his mother, but he also celebrates her existence. His strategy is to focus on the small moments in life that give our closest relationships their meaning.

Death and art go hand-in-hand. In fact, loss has often inspired enormous creative innovation. Still, meditations on death can be somewhat one-note, forcing the reader to experience, over and over, the all-consuming sadness that comes from grieving. In his newest collection of poetry, Time Is a Mother, Ocean Vuong masterfully eludes this obstacle. The poet’s language recognizes the trauma of death, but also revels in the glory of life . In this book, Vuong grieves the loss of his mother, but he also celebrates her existence. His strategy is to focus on the small moments in life that give our closest relationships their meaning.

The expectations for Vuong are high. His recent novel On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous turned into a best-seller and his previous poetry collection, Night Sky with Exit Wounds, was a critical success. This collection reprises some of the flourishes in Vuong’s earlier writing, particularly the way he focuses on the smallest, most fleeting moments to discover surprising emotional resonances. For him the beauty of life is found in the minuscule. In Time Is a Mother that means examining the tiniest memories of his mother.

Still, Vuong moves in a new direction here, embracing self-reflection. He is not only meditating on the loss of his mother, but on the ways that writing and language facilitate (and enhance) the grieving process. The poems here are quite meta; he is investigating what it means to write about loss, the psychological mechanics of what he is experiencing. Consider the final stanza of Vuong’s climactic multi-page poem “Dear Rose,” in which he writes:

bullets salvaged & exiled

by art Ma my art these

corpses I lay

side by side on

the page to tell you

our present tense

was not too late

For Vuong, the writing itself becomes a way to perpetuate life, to confer a kind of immortality. By alluding to his mother in the present tense, she is not really gone. His words are corpses, yet read by others on the page they (and his mother) come to life.

This push towards self-consciousness also takes the form of Vuong’s presence, as a detached persona, in the poems. He frequently writes about himself in the second person, usually a sign that his sadness (or joy) has become overwhelming. “Tell Me Something Good” is an example of how Vuong deftly protects his emotional balance. He needs to depersonalize his language in order to describe his childhood.

You want someone to say all this

is long ago. That one night, very soon, you’ll pack a bag

with your favorite paperback & your mother’s .45,

that the surest shelter was always the thoughts

above your head. That it’s fair – it has to be –

how our hands hurt us, then give us

the world. How you can love the world

until there’s nothing left to love

but yourself. Then you can stop.

By detaching himself from his childhood, Vuong finds it easier to access his deepest memories and to arrive at a more powerful state of understanding, a compelling acceptance of loss.

It should be noted that, in some of his poems, Vnong’s self-conscious excavation of the past may become inscrutable. Vuong plays with form and structure throughout Time Is a Mother, often avoiding punctuation and scrambling up his stanzas and line breaks. For the attentive reader, this challenge rewards because it forces a greater attentiveness to the language. In this sense, Vuong is very much a modernist. But for those who hold, as Mary Oliver would put it, that poems are like prayers, these indirect explorations of mourning may contain too much to grapple with. Consider, for example, Vuong’s stylistic choices in his poem “Skinny Dipping”:

in summer’s teeth

like the blade

in a guillotine I won’t

pick a side

my name a past

tense where I left

my hands

The formatting of the poem makes it a somewhat daunting read, from the lack of punctuation and the mid-thought line breaks to the staggered line placement. Still, Vuong’s strategy, though difficult, is necessary: the lack of punctuation makes the poem seem to be unending, a forever testament to the ecstasy of youth. The poet makes powerful use of a paradox here, as in the rest of the collection: the mid-thought line breaks give the poem an erratic, spontaneous feel, but the regimented line staggering insists on structure, even a sense of uniformity. By yoking together intimacy and distance, Time Is a Mother dramatizes how love and loss subtly intertwine.

Henry Chandonnet is a current student at Tufts University double majoring in English and Political Science with a minor in Economics. On-campus, he is an Arts Editor for The Tufts Daily, the preeminent student-run campus publication. You can reach out to him at henrychandonnet@gmail.com, or follow him on Twitter @HenryChandonnet.

[…] new enlightening details that have a life of their own,” says The Guardian. Artfuse describes Time is a Mother as a “dazzling investigation of love and loss, inspiring both nostalgia […]

[…] – he uncovers new enlightening details that have a life of their own,” says The Guardian. Artfuse describes Time is a Mother as a “dazzling investigation of love and loss, inspiring both nostalgia and […]

[…] – he uncovers new enlightening details that have a life of their own,” says The Guardian. Artfuse describes Time is a Mother as a “dazzling investigation of love and loss, inspiring both nostalgia and […]

[…] – he uncovers new enlightening details that have a life of their own," says The Guardian. Artfuse describes Time is a Mother as a "dazzling investigation of love and loss, inspiring both nostalgia and […]