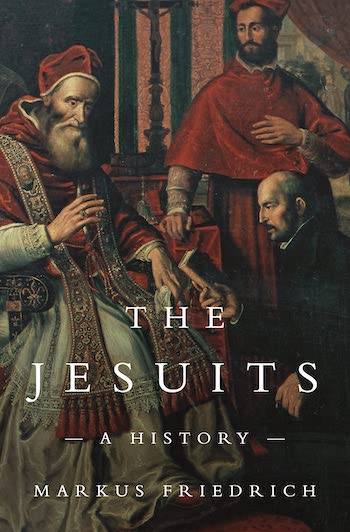

Book Review: “The Jesuits: A History” — The Order Continues

By Thomas Filbin

Markus Friedrich, a professor of early modern history at the University of Hamburg, has written a scholarly but immensely readable history of the order that will appeal to an audience beyond the Catholic tradition.

The Jesuits: A History by Markus Friedrich. Translated by John Noël Dillon. Princeton University Press, 854 pp., $39.95.

There is an old joke that the Jesuits are a Catholic religious order whose purpose is to establish colleges with good basketball teams. That said, the history of the order has been dogged almost since its founding with pejoratives. Over the centuries, the word “Jesuitical” has expanded to mean nuanced dissembling or equivocating, as if their powers of intellect could readily be used for scholastic quibbles, mental reservations, and angels dancing on the head of a pin. Who are these priests who have a direct oath of obedience to the Pope and are thought of as his shock troops, God’s Marine Corps? Full disclosure: I spent four years at a Jesuit preparatory school, Boston College High School. Although I was too immature at the time to realize it, I received an excellent education. The curriculum was the classical regimen, the Ratio Studiorium, which included four years of Latin and three years of Greek (“Laughter and Grief,” as they are sometimes called). Although my intellectual path has been more congenial to such Jesuit educated skeptics such as Voltaire and Diderot, I have nothing but gratitude for my Jesuit teachers. “The memory of the righteous is a blessing” (Proverbs 10).

There is an old joke that the Jesuits are a Catholic religious order whose purpose is to establish colleges with good basketball teams. That said, the history of the order has been dogged almost since its founding with pejoratives. Over the centuries, the word “Jesuitical” has expanded to mean nuanced dissembling or equivocating, as if their powers of intellect could readily be used for scholastic quibbles, mental reservations, and angels dancing on the head of a pin. Who are these priests who have a direct oath of obedience to the Pope and are thought of as his shock troops, God’s Marine Corps? Full disclosure: I spent four years at a Jesuit preparatory school, Boston College High School. Although I was too immature at the time to realize it, I received an excellent education. The curriculum was the classical regimen, the Ratio Studiorium, which included four years of Latin and three years of Greek (“Laughter and Grief,” as they are sometimes called). Although my intellectual path has been more congenial to such Jesuit educated skeptics such as Voltaire and Diderot, I have nothing but gratitude for my Jesuit teachers. “The memory of the righteous is a blessing” (Proverbs 10).

Markus Friedrich, a professor of early modern history at the University of Hamburg, has written a scholarly but immensely readable history of the order that will appeal to an audience beyond the Catholic tradition. The Jesuits have produced teachers, missionaries, scholars, and scientists, as well as saints and sinners. And now one pope, Francis, who was Archbishop of Buenos Aires and a novice master early in his career.

The story begins with Ignatius Loyola (1491-1556), son of a Spanish nobleman who began life as a soldier until a French cannonball shattered his right leg, which led to several operations and a long period of bedridden reading. The latter aroused in him a flame to be a soldier for God. At thirty three he restarted his education in grammar school to learn Latin and be able to attend university. Later, with a few brothers in spirit, he founded the order in Rome: Jesuits took the usual vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience, as well as a fourth vow of loyalty and obedience to the pope. They were willing to do whatever task the pontiff deemed important. St. Francis Xavier was one of members of the first cadre and became the order’s main missionary, traveling to India and Japan but dying before he could make a foray to China. Matteo Ricci took that charge and became fluent and scholarly in the language, history, and literature of classical China. He assisted in creating a map of the world in Chinese characters. Many Jesuits went to the new Americas. Also, the founding of schools became one of the order’s priorities, which established it in the intellectual vanguard of Catholicism. The priests’ lengthy period of spiritual training and study yielded thinkers and doers whose purpose in life was underwritten by their spiritual education.

The conversion of indigenous peoples was a high priority, so the nasty stain of European colonization, slavery, is a crucial part of the story. One of the book’s sub-chapters deals with the Jesuits and the practice. To be honest, Friedrich covers this important matter too briefly. The missionaries came along with the explorers and colonizers ,who used much of the new world for plantations to supply goods to Europe. The labor on these plantations was mostly involuntary, which put the order in the position of having to opine on slavery. Friedrich cites the case of several missionary Jesuits who were uncomfortable with refraining to condemn slavery. Still, the traditional attitude of Christianity in such matters was to argue that its duty was to care for souls, not bodies, an approach attributed to Saint Paul. So the Jesuits “were not blind to the misery of the slaves, but they considered it nonetheless to be of secondary importance.” The Jesuits are guilty of not speaking out about slavery, but then every government, institution, and authority in slave holding regions was complicit (and silent). Perhaps the lesson is that when an unjust practice is both widespread and profitable, justifications will always be found to remain quiescent. Until inhumane practices have been recognized as intrinsically evil, the twisted logic that justifies them will not be discarded.

The great earthquake in Lisbon in 1755 reduced the city to rubble and left an “aftershock…and not just in the geological sense,” Friedrich writes. Religious figures were quick to offer interpretations, insisting that the destruction was the will of God, His punishment. The Jesuit Gabriel Malagrida published a sermon insisting that “God had decreed the destruction…as punishment for the sinful lives of the inhabitants and the Portuguese court.” He also implied that attempts to explain it in physical terms were misguided. All of this caused the Jesuit confessors at Lisbon’s Royal Court to be expelled. Because the Jesuits began to offend powerful figures, as well as the crowned heads of Europe, the pope suppressed the Society of Jesus in 1773. It was not reestablished until 1814.

An etching of St. Ignatius, founder of the Jesuits.

The modern Jesuits have gone beyond their traditional university work and have embraced issues of social conscience: the conditions of the poor, immigrants, and refugees have become priorities. A “social apostolate” has been part of the core mission of the order for decades and many students (myself included) were asked to spend a certain number of hours a week over the course of a year serving the needs of the forgotten. Commitment to social causes has not come without a price. Some more traditional members of the order charge that political activism amounts to Marxism. Friedrich poses the question as: “To what extent could and should criticizing and changing the structure of earthly life be the responsibility of a religious order?” He goes on to note that dozens of Jesuits have paid for their convictions with their lives, including the murder of six Jesuits in El Salvador in 1989 during the civil war.

There is a glaring omission in this volume; there is no mention of the priest abuse crisis affecting the Catholic Church. Jesuits as well as every other type of cleric have been involved. At the very least a brief synopsis would have been proper. Friedrich’s emphasis is on the origins, development, and evolution of the order: he does not have much to say about the badness or goodness of individual priests. He is a sociological historian, an approach which has its limitations for a volume of general history aimed at both Catholics and the generally curious. I can only say that my experience over four years only included (except for a few grumpy old men) interactions with dedicated, honorable priests whose passion was educating the young and trying to be a personal example of Christian principles. The worst criminality in the abuse scandal went beyond the horrid acts of individual men with the young. The cover-ups, lies, and denial of the problem under the guise of divine authority (which continues) only amplified the pain of victims who felt that, for the church, proclamations of justice and moral integrity were nothing but pretense. The oddest part of this tragedy is that in the New Testament Jesus readily forgave ordinary miscreants like thieves and adulterers. He reserved condemnation for only three categories of sinners: religious hypocrites who imposed obligations on others while exempting themselves, people lacking charity and compassion, and those who harmed the young. The hierarchy of the Catholic Church hit the trifecta in this excruciatingly sad chapter of church history.

On a happier note, the order has produced so many noteworthy members that only a few can be mentioned specifically, and these from recent history: Avery Dulles, theologian, son of John Foster; Alfred Delp, German Jesuit and member of the Resistance, shot by the Gestapo; Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, paleontologist; Joseph Callahan, Navy chaplain and Medal of Honor recipient; Daniel Berrigan, anti-war activist; and the inimitable Malachi Martin, author, eccentric, and controversialist. I can only add to this noteworthy pantheon the Rev. John W. Kelley, SJ, my freshman year teacher in English, Latin, and religion. Nicknamed “Waterbury” Kelley for allegedly having lived in Connecticut for a time (or to distinguish him from at least one other John Kelley in the order), he was a serious, old-school teacher who occasionally would lapse into impish humor. He was gently dismissive of some of the silly religious prohibitions and superstitions that had sprung up over time. He was a “live and let live” instructor who loved his work and taught thirteen-year-olds until he was in his seventies. He was not wearing a Roman collar in his retirement picture, but a turtleneck and plaid sport coat. I wrote to him then to congratulate him, saying that he probably did not remember me because I was quiet and only a fair student. He sent me back a card on which he wrote, “I remember all my boys.”

Ignatius had a plan, it seems, which has been five centuries in evolution and is still holding its own.

Thomas Filbin is a free-lance critic whose work has appeared in The New York Times Book Review, The Boston Sunday Globe, and The Hudson Review.

Tagged: John Noël Dillon, Markus Friedrich, Princeton University Press

One need not look too far for an extraordinary Jesuit-Father Robert Drinan-lawyer, human rights activist, and U.S. Representative from Massachusetts.