Book Review: “Letters to Camondo” — An Essential Testament to Jewish Memory and History

By Roberta Silman

This is an extraordinarily beautiful book, its present tense prose creating “an atmosphere of literature,” in Virginia Woolf’s words, its honest probing as illuminating as anything you will read about what it means to be Jewish.

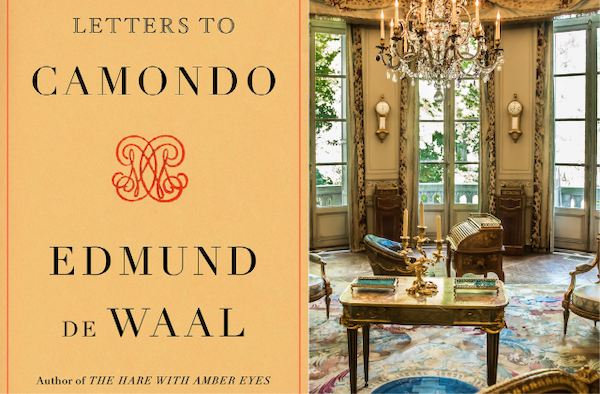

Letters to Camondo by Edmund de Waal. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 182 pages, $28

In the 17th arrondissement of Paris is the Parc Monceau and the famous rue de Monceau, both of which Edmund de Waal got to know when he wrote his unique and heartbreaking memoir The Hare With the Amber Eyes. In 2017, on our last trip to Paris, which we had visited many times, my husband Robert and I went for the first time to that part of Paris (called Jewish Paris even today) to see the house at 81 where Charles Ephrussi, de Waal’s great uncle, lived, and also to visit, at 63, the Musee Nissim De Camondo, which tells an equally heartbreaking story. We were struck not only by the beauty of the objects in that carefully conceived and preserved museum, but also by the trajectory of the lives of these fabulously rich and powerful Jewish families who became targets of anti-Semitism in their adopted countries. In the case of the Camondo family, hatred did not leave a single heir. So, it was not a surprise to learn that Edmund de Waal had written a new book, Letters to Camondo, in which he tells, in the form of imaginary letters to Moise Camondo, their harrowing tale.

This is an extraordinarily beautiful book, its present tense prose creating “an atmosphere of literature,” in Virginia Woolf’s words, its honest probing as illuminating as anything you will read about what it means to be Jewish, and its need to live in someone else’s shoes comparable to the works of Proust and Nabokov and Woolf. It is also enhanced with photographs of the splendid objects in the house, as well as the people who lived there, giving the work an intimacy akin to that of looking through a family photograph album. Because of that this work may be compared to that of W.G. Sebald, but this has none of the trickery and pretension that Sebald employs and thus it is finer, purer both in conception and execution.

That is because, as he explores the flow of life as it was lived in this opulent house, de Waal is also exploring his own life, his work as a potter, his place in the world as a father and husband and Protestant, although his ancestors were Jews. Perhaps most important, he dramatizes how Judaism has exerted itself on lives that mistakenly believed they could escape it. A thread running through this distinctive, quirky book is Edmund’s love for his uncle Iggie, the giver of the famous netsukes, who made a life for himself in Japan with his beloved companion Jiro. That is accompanied by tangents that give context and breath to his story: meditations on color and horses and food and porcelain and Chardin and table settings and cousins and the various clubs and organizations to which Moise belonged. There are also considerations of Edward Drumont and anti-Semitism and the plight of French Jews during the Second World War.

It all starts with the arrival in Paris of the Camondos, members of the wealthy Sephardic banking family who built the gorgeous Kamondo staircase in the neighborhood of Beyoglu in Istanbul. The year is 1869, Moise is nine years old, and he will spend the rest of his life on the rue de Monceau. As de Waal explains in a passage that gives you a sense of his ability to find the telling detail, as well as his sly sense of humor:

The Jewish families who move to the district come from elsewhere. The place offers a chance to bring your family to secular, republican, tolerant, civilized Paris and build something with confidence, something with appropriate scale, something public. Both our families, the Ephrussi and the Camondo, arrive in 1869 — mine from Odessa, yours from Constantinople — and both our families buy plots of land in the rue de Monceau that same year. At number 55 is the Hotel Cattaui, home to Jewish bankers who have moved from Egypt. There are a couple of Rothschilds over the road and two of the three plutocratic and scholarly Reinach brothers live right next to the park…. At number 31 Madame Lemaire holds a salon on Thursdays where the throngs can admire both her watercolors and themselves. Proust grows up around the corner and plays in the Parc Monceau, baked potatoes in his pockets to keep him warm. Theodor Herzl, the architect of Zionism, lives at 8 rue de Monceau during the Dreyfus years.

The original house at 63 was a monstrosity; Moise grew up there, married his wife Irene — from the Cahen d’Anvers family and probably known to most readers from her childhood portrait, “La Petite Irene,” painted by Renoir — when she was 19 and he 31, and they lived here for the first six years of their marriage. When their children Nissim and Beatrice are five and three, Irene “runs off with Count Charles Sampieri, in charge of the Camondo racing stables and her riding instructor.” (Thus, horses.) Moise gets custody of the children and in 1911 embarks on the monumental project of tearing down his parents’ home and getting rid of most of the objects brought from Constantinople and building his own home:

This new house will not be so visible. It will have none of the operatic presence of your parents’ house but will be contained in a restrained courtyard, a house of seven bays, Corinthian pilasters, a modest balustrade. It will be modeled on the Petit Trianon.

Never suspecting that this beautiful structure on which he will lavish so much time and money will eventually become a museum.

Author Edmund de Waal.

Nissim and Beatrice grow up; Nissim is groomed to follow his father’s footsteps and Beatrice is in love with horses, as her mother was. Fate intervenes with World War I; Nissim volunteers to fight, becomes a pilot, and sends his father 258 “funny, warm and touching” letters and postcards, which Moise keeps. On September 5, 1917, a Dorand plane leaves the base at Villiers-les-Nancy on a mission but does not return. For a while it is assumed that Nissim is missing, and letters of encouragement and condolence pour in to the Camondo household. Proust writes of meeting Moise at a dinner with his friend Charles Ephrussi (the model for Swann): “All these memories are very old. They were enough, however, for me to feel the piercing anguish when I learned that you were without news of your son…” Leave it to that childless genius to find the exact phrase to comfort a parent who has lost a child.

Three weeks later Nissim’s death was confirmed. “There is a memorial service on 12 October at the Grand Synagogue. Nissim is awarded a posthumous Legion d’honneur. ‘The catastrophe has broken me and changed all my plans,’ writes Moise.” Because a cruelly tragic death like Nissim’s becomes a fissure in the Camondo family, much as the Dreyfus Affair became in the history of the Jews in France, Moise wants to create a whole, something that can’t be reduced to shards, like the life of a son. As de Waal says,

And I know you, too. To want to make something complete, to need to bring things back together, you have to know what separation feels like, feel dispersion.

You start to make this house and then your son dies. The house changes. It is for him to come back to, it becomes something to give to this mutilated homeland.

Thus, the vision of a museum takes hold. It became Moise’s act of mourning, his way of honoring the dead, and before he dies in 1935 Moise gives it to the government of France, this shrine to his beloved son whose name, Nissim, came from his grandfather and means “miracle” in Hebrew.

Beatrice marries Leon Reinach, whom she has known since childhood; he is a composer from an equally wealthy and accomplished Jewish family and they have a daughter Fanny and a son Bertrand. They lived in Neuilly through the ’20s and ’30s as a “dynastic alliance.” This is the part of the book when we learn about the eminent Reinach family, their connections to other great Jewish families, the houses they build abroad — for example, the Villa Kerylos at Beaulieu-sur-Mer between Nice and Monaco, which my structural engineer husband insisted we visit a long time ago because it is such a remarkable site. It is worth quoting de Waal here:

Villa Kerylos is a temple. Writers and politicians and scholars, musicians and artists, the odd exiled king and lots of Reinach, Ephrussi and Camondo summer here. And there are cousins nearby. Twenty minutes walk away, Beatrice Rothschild, now married to Maurice Ephrussi, builds a pink palace … and fills the house with French furniture and Sevres porcelain. The Villa has nine different gardens, Mexican, Japanese, Florentine, and a “lapidary garden” filled with architectural fragments brought from ruined monasteries and palaces. Her gardeners are dressed like sailors, with red pompoms on their berets in honor of the villa being like a yacht at sea. Which does take it a little far.

There is something surreal about it, something obscene, and of course it does not last.

You have known from the beginning of this review how this story will play out. With the coming of the Second World War darkness descends. All the wealth and eminence, all the clubs and organizations that Moise so proudly joined, Nissim’s ultimate sacrifice in World War I, all the gifts to their beloved France prove to have been for naught. The Nazis invade and all paths to escape, including conversion to Catholicism by Beatrice, are tried. In vain. All the remaining members of this well-connected family perished. Only the runaway in-law mother Irene lived until 1963.

All that is left in Paris is their spectacular house and a commemorative plaque which I first saw in 2017 and will never forget:

MME LEON REINACH

NEE BEATRICE DE CAMONDO

SES ENFANTS FANNY ET BERTRAND REINACH

DERNIER DESCENDANTS DU DONATEUR

ET M. LEON REINACH

DEPORTEES EN 1943-1944

SONT MORTS A AUSCHWITZ

Thus does Letters to Camondo become a valuable addition to what is now considered Holocaust literature. Is it a cautionary tale, a history of French Jewry, a catalogue of a gorgeous museum, a book about the ironies of history? An account of incredibly naive hubris, a living testament to the eternal presence of the dead, or tangible evidence that one can befriend a person one never knew but has grown to love? I am not sure. Probably all of those things, and so much more. What I do know is that this book needs to be read and reread and absorbed by everyone interested in both history and memory (which are two sides of the same coin), and that it will be read long after we, its devotees, are gone. In closing I will give you one last quotation from de Waal: “History is happening. It isn’t the past. That is why objects carry so much, they belong in all the tenses, unresolved, unsettling, essais.”

And that is why after reading this essential book you will better understand where we now are in this precarious time in human history. And why all of us must pay attention as our own increasingly complicated narrative unfolds.

Roberta Silman is the author of four novels, a short story collection and two children’s books. Her latest novel, Secrets and Shadows (Arts Fuse review), is in its second printing and is available on Amazon and at Campden Hill Books. It was chosen as one of the best Indie Books of 2018 by Kirkus and it is now available as an audio book from Alison Larkin Presents. A recipient of Fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts, she has reviewed for the New York Times and Boston Globe, and writes regularly for the Arts Fuse. More about her can be found at robertasilman.com and she can also be reached at rsilman@verizon.net.

Tagged: Edmund de Waal, Farrar Straus & Giroux, Letters to Camondo

Thanks for sending this review ….inspiring us to get the book.

Glad to hear from you as always!