Classical Album Review: The “Spectre Bridegroom” Flies Again — Accompanied by Powerful Music

By Ralph P. Locke

Newly recorded in the original German, Anton Reicha’s Lenore offers a vivid response to Bürger’s famous “Gothic” ballad from 1774.

Anton Reicha: Lenore (“grand musical tableau” for vocal soloists, chorus, and orchestra)

Martina Janková (Lenore), Pavla Vykopalová (Mother), Wojciech Parchem (Narrator), Jiří Brückler (Wilhelm).

Czech Philharmonic Chorus and Brno Philharmonic, cond. Dennis Russell Davies.

Filharmonie Brno 001-2 [2 CDs] 83 minutes.

Anton (or Antoine) Reicha (1770-1836) lived most of his adult life in Paris, teaching counterpoint and fugue at the Conservatoire. The works of his that we hear most often are his many beautifully crafted woodwind quintets. Music histories mention that he taught such stylistically diverse composers as Berlioz, Onslow, Gounod, Franck, and Louise Farrenc. His published treatises on harmony and other aspects of composition remain valuable sources. His piano works often use experimental devices (for the time), such as polytonality and unusual meters; fine recordings of them by Ivan Ilić have been praised in record-review magazines such as American Record Guide.

Reicha got his start in Bohemia, as Antonín Rejcha. He received his musical training and early performing experience in Wallerstein and then Bonn (side by side with Beethoven). He met Beethoven again when he moved to Vienna in 1801. It was there, in 1805-6, that he wrote Lenore, which we today might describe as a cantata or secular oratorio. He called it a “Grand musical tableau with soloists, chorus, and orchestra.” The work, despite strong support from Beethoven, did not get performed in Austria, apparently because the poem, with its heroine’s heretical ravings, had been banned by the censors. Indeed, Reicha never managed to have it performed anywhere, nor was it it published. (The work’s story, by the way, has nothing to do with Leonore, heroine of Fidelio, or with either of Verdi’s Leonoras.)

Fortunately for us, the Czechs have a kind of patriotic interest in Reicha. A Czech scholar prepared an edition of Lenore in 1979, and Czech performers gave the piece its world premiere in 1984. All three existing recordings (including this new one) were made in the Czech lands, mainly with Czech performers (though all are sung in the original language, German). On the present recording, the four soloists, chorus, and orchestra are Czech. The conductor is the renowned American-born Dennis Russell Davies, who has been the Brno Philharmonic’s music director since 2018. His previous positions include many years at the helm of the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra and the American Composers Orchestra. (He co-founded the latter.)

Lenore here lasts 83 minutes and spreads onto two CDs. Each of the two previous recordings was a few minutes shorter and thus fit easily onto a single CD.

The work is a setting of a famous, long, rather creepy narrative poem by Gottfried August Bürger (1747-1794; the poem was first published in 1774). Such poems were often called ballads at the time and are sometimes described as “Gothic” today because many of them are set in a vaguely medieval era. The adjective is also applied to novels dealing with similar subject matter, such as Lewis’s The Monk. I expressed my admiration for the world-premiere recording of Edward Loder’s Monk-inspired opera Raymond and Agnes in the September/October 2021 issue of American Record Guide. Lewis’s The Monk has been adapted three times for the movie screen: in English in 1995; and in French in 1972, with Franco Nero, and 2011, with Vincent Cassel.

Bürger’s poem, a version of the so-called “specter bridegroom” folk-tale type, was so widely loved that other prominent composers would base works on it, including Liszt (a melodrama: spoken narration with piano), Joachim Raff (Symphony no. 5), and Henri Duparc (symphonic poem, adding an acute accent: Lénore).

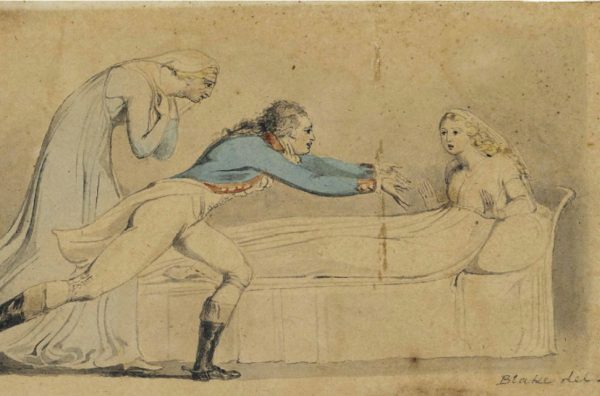

William Blake, “Lenore” (c 1796), illustration for “Leonora, A Tale,” translation by J T Stanley. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Lenore’s beloved Wilhelm has not returned from war. Her mother urges her, ever more emphatically, to trust in God. Lenore raves and threatens suicide, to the consternation of her pious Mama. A figure who resembles Wilhelm shows up and demands that Lenore climb up on his horse. The pair ride furiously and without stopping, surrounded by the howling ghosts of the dead. They pass a crowd dancing around the gallows under the misty moonlight, and finally reach the cemetery, where Wilhelm’s dead body lies. The mysterious horseman’s clothing drops away, revealing a skeleton with hourglass and scythe: the Grim Reaper. Lenore dies and the chorus prays that God receive her soul. The work ends with an orchestral thunderstorm, analogous to the purely instrumental earthquake that ends Haydn’s remarkable Seven Last Words of Christ (for orchestra, or string quartet, without singers, 1796). The poem contains some lines that became world-famous, notably “The dead travel quickly” (which Wilhelm/Death pronounces at three different points in the tale).

Much of the story is sung to us by a tenor Narrator, in the manner of the Evangelist in a Lutheran passion-oratorio. But Bürger also gave Lenore and Wilhelm many stanzas to sing and Lenore’s mother a few passages in which she begs God to forgive her daughter’s despairing outbursts. Reicha makes Lenore and her mother sopranos, and Wilhelm a gruff bass-baritone.

The first recording was conducted by Lubomír Mátl, the second by Frieder Bernius. Both were reviewed in American Record Guide, the Bernius twice (because it was re-released some years later, coupled with Beethoven’s Egmont music). One ARG critic (Charles Parsons) complained about the vocal soloists in the Matl recording. Another, Carl Bauman, reviewing the Bernius, disliked Camilla Nylund (the Leonore) but appreciated the two male singers, whereas Gil French (reviewing the re-release) did like Nylund in that recording (as do I). In recent years Nylund, a vibrant and clearly intelligent soprano, has become a major Wagnerian, as in Mark Elder’s Lohengrin recording (see my review).

All three ARG critics were unanimous in praise of the work. Parsons: “The music has a sweep and grandeur of symphonic proportions not unworthy of Beethoven. The often pleasant and sunny tunes are a delight. The long, slow crescendo of musical excitement is carefully constructed, building to a violent finale.” Bauman: “Anyone who enjoys early middle Beethoven will be captivated by this unknown work.” French: “It has such a strong orchestral thrust that I listened to it as one continuous story, not as a mere collection of arias and recitatives.”

Reicha provides attractive and accomplished music in a variety of styles, including a curiosity-arousing overture that could stand alone as a concert piece. The duet for Lenore and her mother is powerful, as is the one when Wilhelm/Death first shows up and commands Lenore to join him on his horse. In both cases, the characters sing at cross-purposes, creating palpable tension instead of (as often in opera duets) a comforting sense of compatibility.

The chorus sings a gorgeous motet in contrapuntal style as Wilhelm and Lenore, perched together on his galloping steed, view a funeral procession for an unknown dead person (the actual Wilhelm, as we will find out). An ironically cheerful funeral march in the orchestra (under explanatory sung lines from the Narrator) leads to mysterious, flighty string and wind figures as unknown spirits swirl around the gallows. I particularly enjoyed a “pantomime and dance of the spirits” for orchestra alone (No. 25). Several of the orchestral passages in the work reminded me of Berlioz. Did Reicha, I wonder, ever show the manuscript score (or other equally imaginative works of his) to his pupil?

Louis Boulanger, “Witch’s Sabbath,” (1832). Photo: The Athenaeum

Gil French complained that he got a little tired of the creepy music in the last half-hour of the work, but he admits to not having access to the poetic text. (The re-release of the Bernius recording provided only a plot summary.) I found the various passages of “horror” music quite as involving as, and some of them similar to, what Weber would write for the Wolf’s Glen Scene in Der Freischütz 15 years later.

Throughout the new recording, the Brno Philharmonic plays cleanly and with good intonation, though without the incisiveness of the Virtuosi di Praga (under Bernius). Davies also pauses briefly between certain numbers, emphasizing the work’s roots in oratorio rather than opera. The chorus sings with rich sonority and perfect intonation.

The four soloists are technically fine, except that the tenor’s coloratura is sometimes smeared. They all seem aware of the meaning of the texts, but they could have improved their pronunciation. The tenor-Narrator overarticulates certain weak final syllables such as in “Adern,” and the baritone (playing the bad guy, or non-guy) has trouble with ch, as in “Liebchen.” The soloists on the Bernius recording are as good or better at every point.

Still, this is, all in all, a highly capable and style-aware recording of an important work, nicely edited from a live performance in February 2020 (with some touch-ups made during the pandemic: June 2020). It can be streamed at Spotify and other sites. The 2-CD set can be purchased from the website of the Brno Philharmonic. The CD version is well presented, with full texts in German, Czech, English, and French. I noticed some oddities in the English and French translations; perhaps the unnamed translator(s) based those two on the Czech translation rather than on the German original.

By the way, the German poem and a colorful rendering into English verse by the 16-year-old poet (and painter) Dante Gabriel Rossetti have now been made available online at WikiSource. The wonders of the Internet!

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and of course The Arts Fuse. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, Bilbao, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich).

Tagged: ANTON REICHA, Brno Philharmonic, Czech Philharmonic Chorus, Lenore

[…] Classical Album Review: The “Spectre Bridegroom” Flies Again — Accompanied by Powerful Music Newly recorded in the original German, Anton Reicha’s Lenore offers a vivid response to Bürger’s famous “Gothic” ballad from 1774. artfuse.org […]