Book Review: “Divine Images” — William Blake’s Imagination as Mankind’s Saving Grace

By Bill Marx

The author’s aim is to render William Blake’s complex vision understandable to novices. It is a lucid effort, though the book presents a disappointingly conventional overview of the artist’s achievement.

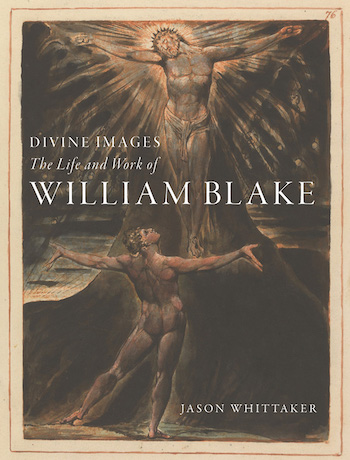

Divine Images: The Life and Work of William Blake by Jason Whittaker. Reaktion Books, 380 pages, 90 color plates, 20 halftones. $50.

This year marks the bicentennial of one of William Blake’s prophetic masterpieces, Jerusalem: The Emanation of the Giant Albion, an illuminated poem made up of 100 engraved and watercolor plates. It took Blake over 15 years to years complete, and he labored on this four-chapter epic in poverty, living in two rented rooms with his loyal wife, Catherine. According to Blake scholar Susanne M. Sklar, who has written a superb book charting the theatrical power of this sui genius precursor to book art as well as the comic book and the graphic novel (Arts Fuse review), the couple lived on about £60 a year.

Jerusalem is a complex visual/literary epic, an unruly allegory that dramatizes, through personal mythic personifications, how our imaginative capacities have been deformed (or fragmented) by the deadening repression of religious, economic, and political authority. Few at the time really understood Blake’s conception of “Mental Fight.” Despite years of derision, incomprehension, and poverty, the artist/poet never stopped working, heroically, on Jerusalem. He colored the final version in 1821 as a gift to his wife.

Filled with images of mysterious beauty, Jerusalem, as well as Blake’s other illuminated books, continues to mystify, despite the determined efforts of explicators (Northrop Frye and Harold Bloom among them) and appreciative artists, including W.B. Yeats. So, even at this late date, Blake remains a paradox. His reputation has risen astronomically — he is now considered one of England’s greatest artists — yet few who admire his images are all that familiar with, or can speak with confidence about, his trenchantly iconoclastic vision, which some critics still patronize as eccentric or inscrutable. Others insist that his dream of imaginative renewal has never been more necessary. In 1935, Frye wrote in a letter, “Read Blake or go to hell, that’s my message to the modern world.”

There’s not a sense of a world at stake in Jason Whittaker’s solid Divine Images. The author’s aim is to render Blake’s complex message understandable to novices. It is a lucid effort, though the author, the Head of the School of English and Journalism at the University of Lincoln, presents a disappointingly conventional overview of the artist’s achievement. Whittaker claims early on that this will be a guide to Blake’s challenging mythology, but he provides broad strokes rather than clarifying details. He is content to lead a chronological march through Blake’s early days as a reasonably lucrative engraver to his final years as a marginalized dissenter, buoyed by the support of a group of younger artists, such as Samuel Palmer, who recognized Blake’s brilliance though they didn’t comprehend his vision, which thickened in reaction to the violence of the French Revolution.

Plate 6 from William Blake’s Jerusalem — Spectre over Los.

Whittaker conveys the essential tenets of Blake’s thought sensibly, and he looks with assurance at his visual brilliance, putting Blake’s pictorial achievement in careful context, placing particular value on the artist’s later work, such as his illustrations of the Book of Job and Dante’s Divine Comedy. He also brings in contemporary critical views of Blake, such as his treatment of racism along with charges of misogyny in his depiction of females. Whittaker has little to say about au courant speculations touching on the prophetic books and homosexuality as well as speculation about the poet and hyperphantasia. Once Whittaker leaves the well-worn biographic trail, Divine Images runs aground — his final chapter is on Blake’s legacy and it is a fudged hodgepodge: we are informed how the Pre-Raphaelites and Yeats embraced the poet, but there is nothing on how literary critics, such as S. Foster Damon, Frye, and others, were instrumental in bringing about Blake’s refurbishment. We are given examples of contemporary artists Blake influenced, such as the band U2, but Whittaker’s selections lack thematic rhyme or reason. As for America, it is good that poet Gary Synder is mentioned in connection with Blake’s anticipation of environmentalism. But where is Virgil Thomson’s “Five Songs from William Blake”? And it is a shame that Whittaker leaves out Esperanza Spalding’s terrific jazz version of “The Fly.” But then every Blake lover will be able to come up with his or her own list.

Just what is Blake’s enduring legacy, to Whittaker? He is attentive to Blake the social rebel, but he seems more interested in slotting him into a nonthreatening Christian context, continually reminding us of the central importance of Jesus. There is nothing to fear in Blake’s seemingly anarchistic art — once it is properly understood. At one point, Whittaker assures us that “Blake’s radicalism as a writer was often due not to his clear ability to perceive the injustices of experience, but rather his belief in the power and importance of innocence as a fundamental part of our humanity.” That doesn’t jibe well with Blake’s demand for unending transformation: “Without contraries is no progression. Attraction and repulsion, reason and energy, love and hate, are necessary to human existence.” Justice and injustice would seem to be part of that elemental tension. Also, as T.S. Eliot observed of Blake, “He was naked, and saw man naked, and from the centre of his own crystal…. There was nothing of the superior person about him. This makes him terrifying.” An articulation of an elemental tension in Blake’s art — a utopian/dystopian yin-yang whose evolution shapes, for him, what it means to be a living rather than a near-dead human being — isn’t to be found in Divine Images. For someone interested in learning about Blake, the volume is a solid and informative first step before moving on to Peter Ackroyd’s biography and Leo Damrosch’s Eternity’s Sunrise.

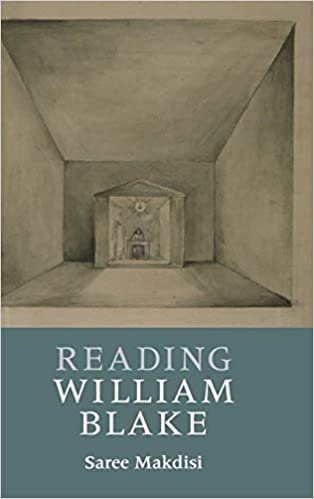

Beginners who want to learn how and why Blake remains radical should turn to Saree Makdisi’s Reading William Blake (University of Cambridge, 2015). (For some reason, Whittaker ignores this volume as well as Makdisi’s magisterial William Blake and the Impossible History of the 1790s in his Select Bibliography.) It is one of the best introductions to Blake’s unruly genius I have read, offering perceptive looks at selections from Songs of Innocence and Experience and Marriage of Heaven and Hell; there are also astute references to Blake’s early prophetic books. Makdisi is particularly good at exploring how Blake’s individuality as a maker of books, whose contents were often revised and changed, illuminates his artistic vision, shaping his distinctive perceptions of time, joy, and desire. The efficacy of the imagination was inevitably linked to the power of creative practice.

Beginners who want to learn how and why Blake remains radical should turn to Saree Makdisi’s Reading William Blake (University of Cambridge, 2015). (For some reason, Whittaker ignores this volume as well as Makdisi’s magisterial William Blake and the Impossible History of the 1790s in his Select Bibliography.) It is one of the best introductions to Blake’s unruly genius I have read, offering perceptive looks at selections from Songs of Innocence and Experience and Marriage of Heaven and Hell; there are also astute references to Blake’s early prophetic books. Makdisi is particularly good at exploring how Blake’s individuality as a maker of books, whose contents were often revised and changed, illuminates his artistic vision, shaping his distinctive perceptions of time, joy, and desire. The efficacy of the imagination was inevitably linked to the power of creative practice.

One of Blake’s major targets was the rise of mechanized routine, a dehumanization that he recognized as “the very basis of modern economic and political formations.” According to Makdisi, his response was to suggest that our survival depends on the embrace of imagination and making: “our own existence is bound up with our imaginative and creative efforts; art as such is in this sense only one manifestation of our more general predisposition, our striving to sustain our being through imaginative and creative practice, without which we are, for Blake, truly lost in that we abandon or are stripped of a certain degree of our own being.” For him, exercising the imagination properly was a matter of life and death, a primal prerequisite for a meaningful existence. Given the state of the world, there is still something very terrifying about that demand.

Bill Marx is the Editor-in-Chief of the Arts Fuse. For just about four decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and the Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created the Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Tagged: Bill-Marx, Divine Images: The Life and Work of William Blake, Jason Whittaker

Thank you for reviewing books on Blake! It’s a pleasant surprise to see Blake making an appearance on the Arts Fuse. He’s notoriously difficult to write about, and it takes an experienced eye to review Blake criticism.