Book Review: Harold Bloom’s Final Testament to the Saving Power of Literature

By Lucas Spiro

Here’s to the late Harold Bloom. Do yourself a favor. Get up early (or whenever) and read something that matters.

Take Arms Against a Sea of Troubles: The Power of the Reader’s Mind Over a Universe of Death by Harold Bloom. Yale University Press, 772 pages, $35.

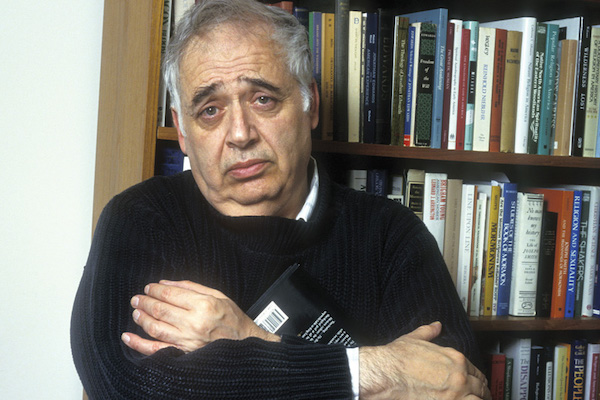

Harold Bloom, possibly America’s most (and last) famous literary critic, died at the age of 89 on October 14, 2019. That was eight days before the expiration date “three charming ladies of Gypsy descent — in Wales, Jerusalem, and Los Angeles, each ten years apart” gave him when they read his palm. He nearly got his money’s worth. Just before he passed away Bloom was busy with his life’s work – reading and writing and reciting poems, seeking wisdom, if not truth, and sharing it with others.

Harold Bloom, possibly America’s most (and last) famous literary critic, died at the age of 89 on October 14, 2019. That was eight days before the expiration date “three charming ladies of Gypsy descent — in Wales, Jerusalem, and Los Angeles, each ten years apart” gave him when they read his palm. He nearly got his money’s worth. Just before he passed away Bloom was busy with his life’s work – reading and writing and reciting poems, seeking wisdom, if not truth, and sharing it with others.

For more than a half-century, Bloom enjoyed academic and popular success driven by his prolific adherence to a deeply aesthetic criticism inspired by notions culled from Freud, the Kabbalah, and deconstruction. His enemies were members of what he deemed the “School of Resentment,” theoretical modes, usually politically orientated, that dominated the academy since the ’70s. Staring the “Great Perhaps” in the face, Bloom gives up on old foes and dredges up such venerable questions as “What can literary criticism, of whatever variety, tell us about such dark matters of speculation as immortality, resurrection, and redemption?” And “What are the frontiers of literary criticism?”

Bloom’s last book, Take Arms Against a Sea of Troubles was written over the course of his final months, “much of it dictated to generous assistants in hospitals and rehabilitation centers.” It was published a little more than a year after his death in November 2020, while the world was gripped by cascading crises that included: the mass death caused by the pandemic (exacerbated by the ineptitude of government officials); fallout from a chaotic presidential election whose inanity was dangerously supplemented by a (continuing) mania about voter fraud; and a global economic system that is becoming increasingly and dangerously lopsided, with billionaires piling obscene profits on top of their already Croesus-like mountains of wealth.

The arms Bloom advises we take up against our sea of troubles are the poems and prose that gave him so much joy, inspiration, sadness, pain, and vigor over the course of his life. These texts also enlivened his preparations for death. “When I say to myself and to others that reading helps in staying alive,” he insists, “I am aware that I am being metaphorical.” But, “if life is to be more than breathing, it needs enhancement by knowledge or by the kind of love that is a form of knowledge.” That knowledge is, at least for him, arrived at through “poetic thinking.” And for Bloom, embracing that kind of thinking is “critical wisdom,” which can only be found through a renewed love of the best of Western writing.

Poetic thinking about poetry denies the illusiveness of character, shrugs off epistemology even as it does metaphysics, and brings together the figures that make up poetic tradition. Those tropes emerge from a matrix of complex relations, historical and psychic, linguistic and imagistic, that work together so as to manifest a raw power that is now difficult to locate elsewhere, whether in theology or in philosophy.

Bloom’s theoretical framework is supposed to be about valuing the textual, but his application of “critical wisdom” to his own body of writing, along with his chosen “transcendent literary geniuses,” is as eccentric as it has always been. This time around his ruminations are keyed into his imminent demise. His methodology, based on close reading that is supported by an intimate and expansive knowledge of the “great works of literature,” is not about scholarship so much as it is about enthusiasm, passionately justifying the value of imaginative literature as a salve for the world’s woes.

After an unfocused introduction rifling through some of his established themes — tropes, transumption, misreadings — and a few of the writers over which he has spilled much ink — Shakespeare, Shelley, Milton — and some of the book’s supporting players — Nietzsche, Vico, Freud — Bloom outlines “The Rhetoric of Poetic Thinking.” This uses “transumption,” or the “trope that revises earlier figurations so as to make them seem belated, and … takes us into the realm of a diachronic rhetoric.” Bloom admits this process has not been “fully formulated.” “Tropes are not so much figures of knowledge as they are urgings or willings”; “critical wisdom” is about treasuring poetic “urgings” toward heightened vision. Bloom calls himself “a devout Emersonian,” and he is ever eager to embrace “the optative mood raised to sublimity: unbounded desire for what is not.” These poets create human freedom through their imaginative powers: they are “liberating gods.” This will require many readers to take a leap of faith. Before they do, they may wonder if the rewards of literature may be more diverse than found in Bloom’s heaven.

Like most of his books, Bloom devotes most of his attention to the writers that could broadly be considered part of the Western Canon. (His 1994 book is authoritatively entitled The Western Canon.) He begins with some essays on Milton and Shakespeare, followed by a long and fascinating chapter on Milton and the singular, enigmatic William Blake. He then moves through some Romantics, spending a great deal of time with Shelley and others before reflecting on the American Sublime — Walt Whitman, Robert Frost, and Wallace Stevens. He plumbs the modernism of W.B. Yeats and D.H. Lawrence before reaching an arduous chapter on Freud and, finally, returning to Shakespeare and Dante in the chapter he was writing just days before he died. Need it be pointed out that women and Others are not of “liberating god” stock.

It’s tempting to regard the book’s portentous subtitle – “The Power of the Reader’s Mind Over a Universe of Death” — as literary self-help run amuck. (The line is taken from Milton, whose work casts a long pall over the book.) Early on, Bloom notes that “secular and disenchanted readers in time may well confront something like the chaos through which Milton’s Satan heroically voyaged, named by the poet: ‘a universe of death,’” and asks, “How shall such readers augment the power of mind to sustain their own voyage?” “It is difficult/to get the news from poems/yet men die miserably every day/for lack/of what is found there,” wrote William Carlos Williams in much the same spirit. But is there anyone today (outside of the lit-crit biz) who seriously talks about reaching for an imaginative work of Western literature in order to deal with the Climate Crisis?

Not really. It is the best and worst time for Take Arms Against a Sea of Troubles. On the one hand, Bloom’s wild assertions of the power of the aesthetic are admirable because he doesn’t use criticism as a cheap substitute for politics. (Let’s not go into the issue of art or criticism as a substitute for religion.) But his earnest passions and exhortations, this final yelp of an aesthete hailing the indispensability of the poets of yore, hover uneasily between the world the pandemic buried and the world it will beget.

There is some interesting mapping of literary influences. Bloom traces, albeit subjectively, a through-line that connects many of the English language’s most accomplished artists. He does go into depth a few times, but the analyses are often brief or hurried for most of the book. He’s running out of time and has to get it all out there, in whatever form it takes. When Bloom focuses on himself, the narrative flounders. But when he looks for the final time at the verses he has internalized, lovingly lived with, in some cases chanted, for over half a century, the writing casts an undeniable spell. We are taken through the words of authors that meant the world to Bloom — that inspired him, confounded him, and comforted him.

The late Harold Bloom. Photo: Wiki Common

Still, as wide-ranging as the book may be, it is not a “Cook’s Tour of Bloom’s faves,” as Terry Eagleton labeled the critic’s popular survey How to Read and Why, “boring the reader with plodding plot summaries or ludicrously long quotations and then adding a few amateurish, undemanding comments.” Take Arms Against a Sea of Troubles is the product of a man who is literally running out of time and words. Are there ludicrously long quotations? Yes, but they are worth reading. Does Bloom ramble? Sure. But — and I can’t stress this enough —this is literary criticism penned in extremis. Bloom was dying as he was writing this tome, which gives it a kind of deathbed heft.

Bloom lodges a few directives in the text like a grandparent frantically telling whoever is around something, anything, that might pass for hoarfrosted wisdom. A line from Wordsworth’s The Prelude inspires a memorable sentiment. “Rise up at dawn,” Bloom implores, “and read something that matters as soon as you can.” Of course, what matters is relative. I know I am not alone in feeling that reading what “matters” is becoming more difficult than ever. Perhaps it is enough to sit down and read — and I mean really read — a text that might take a while, that might not wrap up with a simple-minded moral at the end, that might not reveal much of anything until you think about it much later — if at all.

There’s a TV commercial for one of the tabloids here in Ireland that throws a barrage of words across the screen.

NEWSSPORTRACINGGOSSIPGANGLANDFUEDSFOOTBALLGAASHOWBIZTREAMINGCOVID.

To me, the goulash of words mimics the relentless onslaught of digital media; words, objects, images, and events tossed out at light speed without distinction or context or meaning. I fear too many of us have grown accustomed to the nonstop onslaught and tricked ourselves into believing we can divine the secrets of the chaos if we can just keep up with it all.

So, here’s to Bloom. Do yourself a favor. Get up early (or whenever) and read something that matters.

Lucas Spiro is a writer living in Dublin.

Great piece…I’m glad you’re sticking up for Bloom and giving him some generous time and attention. Sometimes I think it’s less about reading Bloom’s own thoughts (which are kind of dense and seem to make sense only to someone who is as massively erudite as him) and just letting him preach about the writers who still matter, all these years later.

I wonder if you can say a little more about the fascinating chapter on Milton?