Arts Remembrance: Charley Pride — The Man Who Sang Honky-Tonk Best

By Noah Schaffer

When Charley Pride did display anger, it concerned how the country music establishment treated older artists.

There’s an old maxim in the African American community that you have to be “twice as good to get half as far.” The saying is now considered dated, but the career of Charley Pride was a sterling example of its aptness: he had to be twice as good — and twice as country — to become the first Black country music superstar. It was a role he occupied pretty much by himself until very recently. Pride passed away this weekend from complications related to Covid-19 at the age of 86.

Pride was far from the first Black country artist. The death announcement by Pride’s publicist generously mentioned that the Grand Ole Opry itself was launched by harmonica player DeFord Bailey in 1927. A year later Bailey was the first musician to make a record in Nashville.

But Bailey and his Black peers had been largely erased from the memory of mainstream country by the time a sharecropper’s son and Negro League pitcher named Charley Pride arrived in Nashville in the mid-’60s. A record deal wasn’t immediately forthcoming, but eventually producer Cowboy Jack Clement convinced RCA honcho Chet Atkins to give Pride a chance.

Stories — perhaps apocryphal — abound of unsuspecting radio listeners who were shocked to arrive at a Pride concert and discover he was Black. In case there was any confusion what the Black vocalist on the cover was singing, RCA credited Pride’s debut to “Country Charley Pride.”

Once Pride was granted access to country radio, he remained a mainstay thanks to his flawless baritone delivery of songs that embodied the best kind of country storytelling: The desolate weariness of “Is Anybody Going to San Antone?,” the honky-tonk jealousy of “Does Your Ring Hurt My Finger?,” and the down-home sincerity of “All I Have to Offer You Is Me,” and the tale of the hardscrabble childhood Pride endured in a “Mississippi Cotton Picking Delta Town.”

By the early ’70s Pride’s popular stature had been established thanks to crossover hit “Kiss an Angel Good Morning” and his regular appearances in the winners’ circles of awards shows. He was one of country’s greatest ambassadors, his music adored everywhere from Ireland to the Caribbean. (Jamaican producer Joe Gibbs is said to have gone bankrupt after being caught falsely taking songwriting credit for JC Lodge’s hit reggae cover of Pride’s “Someone Loves You Honey.”)

But any hopes that he would be a Jackie Robinson-like figure, one who would open the door for other Black country stars, seemed illusory when the music of great artists like O.B. McClinton and Linda Martell was lost in the shuffle. The suspicion that Nashville viewed one Black star as enough was embodied by R&B singer Bobby Womack’s unsuccessful attempt at convincing his label to title a 1976 collection of country material “Step Aside, Charley Pride, Give Another Nigger a Try.”

Journalists who hoped that such a pioneering artist would offer pointed racial or political commentaries were disappointed when they interviewed him. Although Pride would detail the harrowing racism he experienced in the Jim Crow era, he largely stuck with a genial, aw-shucks persona. Both his autobiography and a 2019 PBS “American Masters” documentary find him sticking to his characterization of himself as a “staunch American,” a man proud of his hard work and business acumen, the latter including owning a piece of the Texas Rangers baseball club.

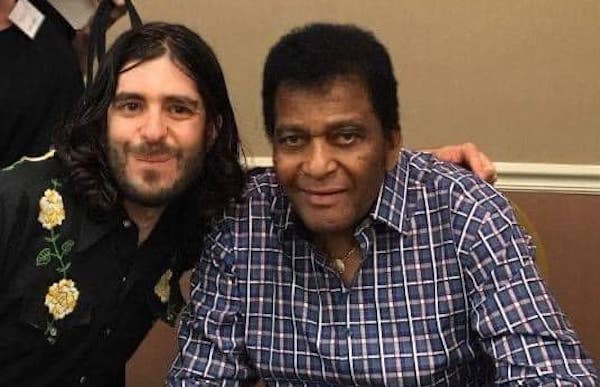

Arts Fuse Noah Schaffer critic and the late country music legend Charley Pride in 2018. Photo: Noah Schaffer.

When Pride did display anger, it concerned how the country music establishment treated older artists. His 1985 split from RCA was acrimonious. A music executive I know was excited to meet Pride backstage a decade later. But Pride refused his handshake when he learned the man was employed by the Country Music Association.

Pride could be enigmatic, but he was astonishingly accessible for such a major cultural figure, even by country music standards. A modestly priced subscription to his fan club yielded both a newsletter full of his favorite recipes and an invitation to say hello backstage anywhere Pride was appearing. Long after the Nashville Fan Fair week had morphed into a series of CMA-sponsored mega-concerts, Pride kept his fan appreciation breakfast, held in a nondescript conference room at a mid-tier hotel far from downtown. I attended one of those affairs in 2018. Charley’s wife of over 60 years, Rozene, hosted the morning, at one point picking contestants to take part in what she called the “Not So Newlywed Game.” Darius Rucker, one of several mainstream country stars of color to emerge in recent years, dropped by to say hello.

Of course the affair concluded with a meet and greet, and besides getting some vintage vinyl signed I figured it’d be polite to pick up a copy of Pride’s latest CD. On the drive home I popped in Music In My Heart with low expectations. But despite being a small-label release that garnered almost no critical or popular attention when it was released, the 2017 release turned out to be a first-class collection of real honky-tonk country, sung by the man who sang it best.

Over the past 15 years Noah Schaffer has written about otherwise unheralded musicians from the worlds of gospel, jazz, blues, Latin, African, reggae, Middle Eastern music, klezmer, polka, and far beyond. He has won over 10 awards from the New England Newspaper and Press Association.

Noah I thoroughly enjoyed reading your article about the late Charley Pride!!! He overcame a lot of adversity in his life to become a true country music legend!!! He was a very talented singer & musician who dearly loved his fans wherever he performed!!! He didn’t allow his race to hold him back from what he wanted to show the world of country music fans!!! RIP CHARLEY PRIDE!!!