Book Review: “I Died a Million Times” — Upwardly Mobile in Film Noir

By Nicole Veneto

I Died a Million Times is an enjoyable and informative read for film noir aficionados and casual movie fans alike, offering a cogent analysis of ’50s gangster noir as a cinema of social commentary.

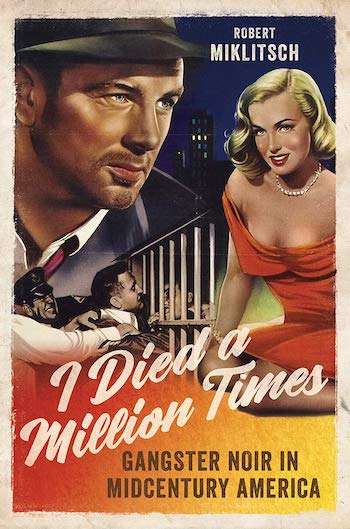

I Died a Million Times: Gangster Noir in Midcentury America by Robert Miklitsch. University of Illinois Press, 304 pages, $27.95 (paperback).

Buy at Bookshop

As Alonzo Emmerich (Louis Calhern), the corrupt lawyer who bankrolls the pivotal jewelry heist in John Huston’s The Asphalt Jungle, famously notes, “‘crime is only a left-handed form of human endeavor.’” It is just another way to score the American dream. Film noir, literally “dark film,” chronicles the peregrinations of adrift go-getters in the shadowy margins of society, from the criminal underworld of mafia gangsters in the ’30s (Scarface, Little Caesar) to the hard-boiled detectives and working men done in by duplicitous femmes fatales throughout the ’40s (The Maltese Falcon, Double Indemnity).

As Alonzo Emmerich (Louis Calhern), the corrupt lawyer who bankrolls the pivotal jewelry heist in John Huston’s The Asphalt Jungle, famously notes, “‘crime is only a left-handed form of human endeavor.’” It is just another way to score the American dream. Film noir, literally “dark film,” chronicles the peregrinations of adrift go-getters in the shadowy margins of society, from the criminal underworld of mafia gangsters in the ’30s (Scarface, Little Caesar) to the hard-boiled detectives and working men done in by duplicitous femmes fatales throughout the ’40s (The Maltese Falcon, Double Indemnity).

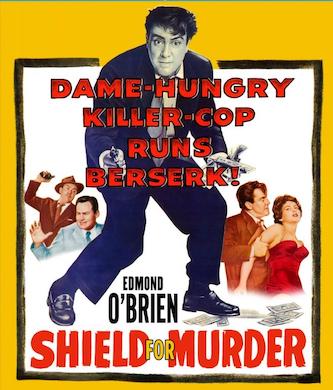

The ’50s are considered by critics to be the final decade of classic film noir, which wound down probing the rancid underbelly of postwar society. On the one hand, the era was seen as the golden age of national prosperity: think suburbia’s white picket fences, upwardly mobile nuclear families nurtured by doting housewives. Times were good: the war had ended years of economic struggle after the Depression. Yet it was also a time of growing social unease fueled by Cold War–infused paranoia. It’s this dichotomy between the self-serving myth of the ’50s and its ugly realities that Robert Miklitsch analyzes in I Died a Million Times. He examines three distinct yet interrelated subtypes of ’50s crime noir: the syndicate picture, the rogue-cop film, and the caper/heist feature. (His hybridized designation is “gangster noir.”) The result is an insightful look into the cultural politics and stylistic motifs at work in well-known classics (The Asphalt Jungle, The Big Heat, and Touch of Evil) as well as lesser-known B-pictures (711 Ocean Drive, Shield for Murder, and The Brothers Rico).

For Miklitsch, ’50s gangster noir articulates “the antinomies and contradictions” of a decade that saw itself as the “‘happy days’” despite what the historical record tells us. He looks at films against a national backdrop of “cultural paranoia and emerging corporatization,” pointing out the turmoil kicked up by the Kefauver Committee Hearings, HUAC and the Hollywood blacklist, suburbanization, the stirrings of the Civil Rights Movement, the rise of television, etc. Along with this discord, gangster noir tapped into the “contentious issue of class in mid-century Cold War America,” a conflict that festered beneath the placid surface of postwar prosperity.

Miklitsch spends ample pages dissecting how the Kefauver Hearings, the Hollywood Red Scare, and studios’ crackdown against labor unions bled into ’50s gangster-noir. But the linchpin of his book is the rise of American consumerism and its effects on postwar class/social relations. Unifying all the films he takes up is an overarching theme of the individual pitted against dominating systems and organizations, be they criminal syndicates with cities on their bankroll or law enforcement in hot pursuit of a ragtag group of jewel thieves on the run. Miklitsch sees these films as registering the consumer anxiety generated by the “vexed dialectic between the individual and the collective.” For all the advertising fodder about a middle-class life for the taking, the American Dream, in actuality, was far more elusive. For the working class protagonists in these films ”crime doesn’t pay, but…neither does a hard day’s work. ” Of course, any attempts to play outside of the rules to achieve upward mobility was rewarded by harsh punishment, in accordance with Production Code guidelines. Although some protagonists are treated with more empathy than others — petty-criminal Dix Handley’s hopes to buy back his family’s farm in The Asphalt Jungle versus rogue-cop Webb Garwood’s self-interested and “perverted [motives] of possessive individualism” in The Prowler — their motivations all boil down to the desire to move up the social and economic ladder.

Noir is a predominantly male-centric subgenre, but Miklitsch is admirably sensitive to the sexual politics in the mix, especially when men’s relationships with (or more accurately, “possess[ion] of”) women envision them as erotic frosting on the cold cash cake. In ’50s gangster noir, “dames” functioned as class signifiers (“100,000 bucks, a Cadillac, and a blonde’) that marked where men fell in the pecking order of social hierarchy and power. With the resurgence of conservative gender norms following the war, pricey trophy wives/mistresses (see a young Marylin Monroe in The Asphalt Jungle) and “pristine,” upper-class “good” women (Janet Leigh in Touch of Evil most notably) gradually supplanted the aggressive — though no less materially driven — femme fatale of the ’40s. Thus female sexuality was domesticated, another step in the commodification of the female body onscreen.

In comparison, Miklitsch’s analysis of the racial politics of The Phenix City Story — a 1955 B-movie dramatizing the assassination of Albert L. “Pat” Patterson, the Democratic nominee for Alabama’s Attorney General, and his son John’s ensuing fight against Phenix City’s criminal underbelly — falls short in its attempt to read a racially progressive subtext into a film that blatantly utilizes Black death and suffering to sensationalize its version of events. As a way of violently dissuading John and his father from joining the local reformist association, syndicate goons abduct and murder a little Black girl, her wide-eyed, lifeless body “tossed like garbage” onto the Pattersons’ front lawn in front of their young children. This nameless girl is the daughter of Zeke Ward, a janitor at the Poppy Club in Phenix City’s red-light district who’s supportive of the reformist association. At the film’s climax, John pursues his father’s murderers to the Wards’ tiny shack of a home on the outskirts of town, arriving just in time to stop them from beating Zeke to death in front of his terrified wife. But before John can exact his own fatal vengeance against the men who gunned his father down, a battered and bloodied Zeke intervenes to remind John of the Lord’s commandment, “Thou shalt not kill.” In light of the Supreme Court’s ruling on Brown vs. The Board of Education a month before Patterson’s assassination, Miklitsch concurs with critic Jonathan Rosenbaum’s reading of Zeke’s character as symptomatic of the nascent Civil Rights Movement and Martin Luther King Jr.’s ethos of nonviolent resistance.

In comparison, Miklitsch’s analysis of the racial politics of The Phenix City Story — a 1955 B-movie dramatizing the assassination of Albert L. “Pat” Patterson, the Democratic nominee for Alabama’s Attorney General, and his son John’s ensuing fight against Phenix City’s criminal underbelly — falls short in its attempt to read a racially progressive subtext into a film that blatantly utilizes Black death and suffering to sensationalize its version of events. As a way of violently dissuading John and his father from joining the local reformist association, syndicate goons abduct and murder a little Black girl, her wide-eyed, lifeless body “tossed like garbage” onto the Pattersons’ front lawn in front of their young children. This nameless girl is the daughter of Zeke Ward, a janitor at the Poppy Club in Phenix City’s red-light district who’s supportive of the reformist association. At the film’s climax, John pursues his father’s murderers to the Wards’ tiny shack of a home on the outskirts of town, arriving just in time to stop them from beating Zeke to death in front of his terrified wife. But before John can exact his own fatal vengeance against the men who gunned his father down, a battered and bloodied Zeke intervenes to remind John of the Lord’s commandment, “Thou shalt not kill.” In light of the Supreme Court’s ruling on Brown vs. The Board of Education a month before Patterson’s assassination, Miklitsch concurs with critic Jonathan Rosenbaum’s reading of Zeke’s character as symptomatic of the nascent Civil Rights Movement and Martin Luther King Jr.’s ethos of nonviolent resistance.

However, the crux of Miklitsch’s argument depends on Rosenbaum’s claim that The Phenix City Story is an “‘authentic’” representation of Alabama in the ’50s: “‘What made the film believably convincing as well as Southern was the racist killing of a little black girl.’”

In truth, the real John and Albert Patterson were staunch segregationists, and John’s subsequent political career in particular benefited from the wave of “intransigent anti-integrationism” that followed Brown vs. The Board. Furthermore, Zeke, his wife, and their nameless, murdered daughter are complete fictions. Their purpose in the narrative is to populate the aforementioned shock scene (even more distressing to witness in the context of 2020) and to invite the White Savior narrative injected into the Pattersons’ fictionalized legacy. In this light, Zeke’s monologue about the morality of nonviolent retaliation, delivered to a man whose real-life counterpart was supported by the Ku Klux Klan when he successfully ran for governor in 1958 (a fact Miklitsch oddly leaves out), rings hollow. Despite this, the scholar concludes his evaluation by claiming that “the historical record does not diminish the liberatory promise of The Phenix City Story.” It isn’t clear who the beneficiary of this “liberatory promise” is. There’s a whole slew of criticism on the marginality of Black identity in film noir. That Miklitsch doesn’t draw on any of this work is puzzling, and disappointing.

Still, I Died a Million Times is an enjoyable and informative read for film noir aficionados and casual movie fans alike, offering a cogent analysis of ’50s gangster noir as a cinema of social commentary.

Nicole Veneto graduated from Brandeis University with an MA in Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, concentrating on feminist media studies. Her writing has been featured in MAI Feminism & Visual Culture, Film Matters Magazine, and Boston University’s Hoochie Reader.

Tagged: I Died a Million Times, Nicole Veneto, Robert Miklitsch.

I thought that the author brought a “fair and balanced” evaluation of the book…and I really appreciated it. As a Noir aficionado, I welcome all perspectives…the more thought-provoking, the better…as the author’s review proves.

I wholeheartedly agree with her assessment of the near invisibility of Blacks in Noir.

However, there’s an excellent portrayal, in the 1948 Noir Moonrise, of a character, by the Black actor Ray Ingram.

Available free on YouTube, the movie has been hailed by Eddie Muller (TCM’s Czar of Noir and a leading expert on Noir films and their preservation) as one of his “Top Ten” Noirs.

Ingram’s portrayal is “everything” a viewer could want…elegant, powerful in both its understated dignity and sagacity, and thought-provoking. And, that his character is the moral arbiter of the story is simply fantastic !

I can’t recommend it highly enough !