Arts Commentary: Meditations on Separation

By Steve Elman

This is what I feel can add: the perspective of a native-born son of the Rochester metro; and a view from the bridge through jazz-colored glasses.

In this summer of our discontents, I have done a lot of thinking. Some of that thinking was prompted by an episode of the radio series Hidden Brain; some by Ibram X. Kendi’s book How to Be an Antiracist; a good deal of it was echoed in or tempered by music I know and love; and some of it is still being shaped by Alice Randall’s new novel celebrating the shining time of Black culture in Detroit, Black Bottom Saints.

In this summer of our discontents, I have done a lot of thinking. Some of that thinking was prompted by an episode of the radio series Hidden Brain; some by Ibram X. Kendi’s book How to Be an Antiracist; a good deal of it was echoed in or tempered by music I know and love; and some of it is still being shaped by Alice Randall’s new novel celebrating the shining time of Black culture in Detroit, Black Bottom Saints.

Then I heard about Daniel Prude, and some chickens began coming home to roost.

I hesitated to write about all of this. After all, what can a 71-yearold White writer say that hasn’t been said already? The last thing a controversy needs is more hot air.

This is what I feel can add: the perspective of a native-born son of the Rochester metro; and a view from the bridge through jazz-colored glasses.

Kendi pointed the way for me. A lot has been written about the importance of How to Be an Antiracist, but I think that other writers haven’t paid enough attention to the thread of self-discovery that runs through it and informs Kendi’s observations. He builds his thinking on lessons he learned from the insights and misperceptions in his own intellectual life. I found his book much richer for his willingness to say, over and over again, “I was wrong.”

That honesty was inspiring, and it sent me to school. I began to listen to my past in a way I hadn’t listened before.

I remembered an uncle telling a joke about “Negroes” and their Cadillacs.

I remembered the Black man I worked with in a summer job in an industrial plant who saved my foot by pulling it from under a multi-ton machine that was being set down on the shop floor.

I remembered my mother, one of the most gracious people I have ever known, expressing her fear of going “down there,” into the Black neighborhoods of Rochester, where her German ancestors used to live and where one German-American butcher still was making weisswurst (or “white hots” in Rochester vernacular) with the recipe our family considered the best in town.

I remembered in my high school years being hungry for something in music I wasn’t getting from Percy Faith or Ray Conniff, going to the library, being intrigued by the cover of Thelonious Monk’s Misterioso, bringing it home, hearing Monk and Johnny Griffin, and thinking, “This is it.”

I remembered that there was one Black man in my high school class, whom I never got to know and whose name I cannot recall.

I remembered my father, an amateur accordionist, playing one of his favorites, an arrangement of Duke Ellington’s “Mood Indigo” that I later realized included a transcription of Barney Bigard’s clarinet solo.

I remembered seeing Thad Jones, Mel Lewis, Richard Davis, and Chick Corea play a concert in 1967 at the Eastman Theater, long before Rochester had an International Jazz Festival.

I remembered laughing at the Amos ’n’ Andy TV show and repeating for years one of the Kingfish’s malapronouncements, “Oh, gimme an ultomato, huh?” eventually even forgetting where it had come from.

I remembered the jazz radio shows hosted by White DJs I admired – Will Moyle, Harry Abraham, and Bill Ardis – and how they played the music of Black artists I came to know from their work.

I remembered the young Black man who ran the freight elevator at the department store where I worked as a stockboy, and how he seemed so worldly-wise even though he couldn’t have been more than three years older than I was.

And I remembered the 1964 riots in the Black neighborhoods of Rochester and how so many of us Whites said, “Harlem, of course. Watts, sure. But how could this happen here?”

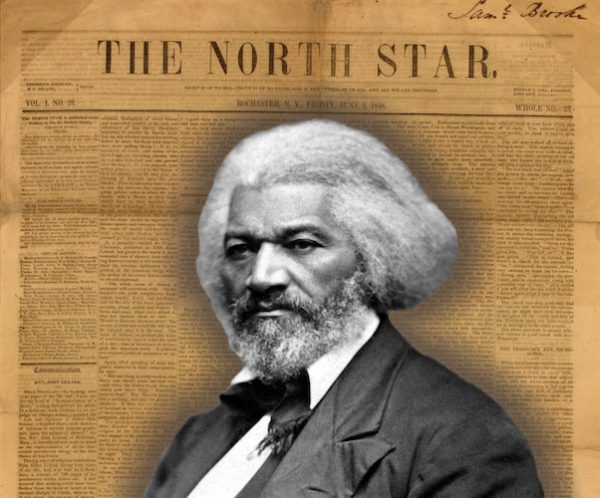

There’s a parade of contradictory milestones in my home town: 1838 through 1851, when the “Colored Population” were shown in their own segregated listing in the Rochester City Directory; 1847, when Frederick Douglass founded his first newspaper, The North Star, there; 1854-56, when the city elected two successive mayors who were part of the Know-Nothings, that doublethinking party that simultaneously supported emancipation for enslaved Americans in the South and opposed immigration of Catholics from Europe like my ancestors; the 1910s, when racial covenants became common practice to prohibit Black ownership in many suburban neighborhoods bordering the city proper; the 1920s, when a Monroe County chapter of the Ku Klux Klan was founded; the ’50s, when the Black population increased significantly and Black employment remained confined to menial jobs, despite a booming local economy boasting one of the lowest unemployment rates in the US; July 1964, when two nights of rioting decimated the city’s Black neighborhoods and resulted in the first use of the National Guard to stem urban violence in a northern city; late 1964, when Eastman Kodak Company, the city’s largest employer, announced (in the wake of the riots) that it was actively recruiting Blacks for the first time; 1979, when Kodak signed on to the Sullivan Principles of fair hiring; 1994, when Rochester elected its first Black mayor, William Johnson.

But history is abstract. While I was doing research on this piece, reality slapped me hard in the face. I came on a 2020 monograph on racial covenants in Rochester prepared by members of the City Community Land Trust and the Yale Environmental Protection Clinic, and I read this:

The Roman Catholic Diocese of Rochester, in purchasing the land that St. James Church would be built on, promised in the deed that the land “shall never be occupied by a colored person.”

That was my family’s church, where we attended mass every Sunday and every Holy Day of Obligation from 1950 through 1963. Had I ever seen a Black face among the faithful? I couldn’t remember one.

Invisible People, as Ralph Ellison might have it. So invisible that the city’s important jazz club, the Pythodd Room, where artists like Miles Davis, James Moody, Wes Montgomery, Shirley Scott and Stanley Turrentine played – where I could have seen and heard them in their prime! – was never reviewed and hardly ever mentioned in the local newspaper of record, the Democrat & Chronicle, until 1970, when its Sunday magazine published a piece on the scene at the Pythodd, as if it were some exotic underground joint rather than a club on the regular circuit of small-city venues frequented by major artists. Of course, it was Down There, and I was too White and too sheltered to realize that the city even had a Scene.

It would have been hard for a White kid to penetrate Rochester’s Scene even if he had known what was going on. Even when I became a small part of Boston’s Scene, in the ’70s and ’80s, I knew I was never living it as native Black Bostonians did.

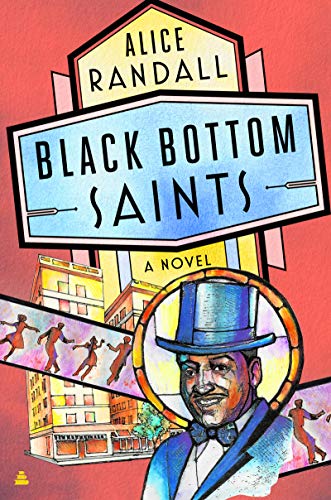

I’m still learning. I’m savoring Alice Randall’s new Black Bottom Saints, a novel in the form of 52 biographical reminiscences of personalities who had an impact on Black Detroit when it was one of the beating hearts of Black culture in the US. Randall filters impressions of the real people on the Scene there in the voice of a real newspaper columnist, Ziggy Johnson, who went everywhere and knew everyone. Her work is giving me my richest chance yet to get behind the scenes of a Scene, to know how independent that Scene is from my own experience, and indeed how little of such a Scene depends on its tangents with White America.

I’m still learning. I’m savoring Alice Randall’s new Black Bottom Saints, a novel in the form of 52 biographical reminiscences of personalities who had an impact on Black Detroit when it was one of the beating hearts of Black culture in the US. Randall filters impressions of the real people on the Scene there in the voice of a real newspaper columnist, Ziggy Johnson, who went everywhere and knew everyone. Her work is giving me my richest chance yet to get behind the scenes of a Scene, to know how independent that Scene is from my own experience, and indeed how little of such a Scene depends on its tangents with White America.

There isn’t much jazz in the book. Nat Cole is there, and Billy Eckstine, along with entertainers like Bubbles and Buck, Della Reese, LaVern Baker, Butterbeans and Susie, Bricktop, and Sammy Davis, Jr. Casual mentions of Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Fletcher Henderson, and other jazzpeople flash by.

I kept hoping for some glimpses of those three jazz prodigy brothers from the Motor City – Thad Jones, Hank Jones, and Elvin Jones, whom Ziggy surely knew of and maybe even knew, since he knew everyone in Detroit. And I kept hoping to get behind the scenes at a rehearsal, to compare Ziggy’s impressions with my own, because I had the chance to taste a little of Detroit’s contemporary Scene, when I was given the chance in 2019 to sit in on a rehearsal by James Carter’s organ trio and to see the artistic camaraderie of Detroiters firsthand.

But Randall’s book is part of the Now in my life, nothing like my Then in upstate New York, where I had to invent a Scene in my head.

My father awakened my perceptions inadvertently when I was 10 or 11. I found him listening to an Art Tatum recording and marveling (as he did so often) at Tatum’s speed and dexterity at the piano. “He’s blind, you know,” he said. “Isn’t it amazing?” If my dad admired him, this man must be a great musician, I thought, and that led to a lifetime of awestruck listening to Tatum, always agreeing with my father’s ghost. I can never hear Tatum play “Without A Song” without remembering that my dad sang the same tune with an amateur choral group. Since only Tatum’s fingers had been shown on my dad’s LP cover, I didn’t learn until later that Tatum was Black. The man’s race hadn’t compromised my father’s esteem, so it never came to matter to me.

Then came Monk, and after finding him, I began devouring jazz recordings in a hopscotch fashion, finding a name in the liner notes of one LP that pointed to someone I should know about, seeking that person out on record, finding another name, jumping to another LP, and on and on, until I realized I was a jazz fan.

The first moment I remember being brought to tears by music was the deeply poignant conclusion of the sessions for Duke Ellington’s . . . and his mother called him Bill . . ., a retrospective of music written by his long-time collaborator Billy Strayhorn, who had died a few months before. Ellington sat meditatively at the piano as his men were packing up and began playing Strayhorn’s “Lotus Blossom.” Fortunately, the producers got tape rolling almost immediately, and Ellington’s personal grief, expressed so intimately and profoundly, was captured, with the few false fingerings adding to the sadness – in one of the very few times he allowed himself to be fully revealed in public. And when I learned later that Strayhorn was gay, that never came to matter either. If Duke had loved Strays so much, what difference could that make?

It took years to formulate what was going on in my head beyond the enjoyment of the music. Something gradually became clear to me, a kind of intellectual mosaic composed of thousands of tiles of listening: I was getting to know these artists personally, hearing them think and work in real time. And I was learning how to hear their feelings between the notes, the feelings of real people, not just their names on record jackets – Ellington’s elegant mixture of stage intimacy and personal distance, Bud Powell’s mental torture, John Coltrane’s spiritual journey, Billie Holiday’s arc of tragedy, Louis Armstrong’s boundless optimism. I had finally been fitted with jazz-colored glasses.

It was inevitable – inescapable – to begin to hear jazzpeople’s feelings about race and place in America, and I came to see the race riots of the ’60s and the turmoil thereafter through those jazz-colored glasses.

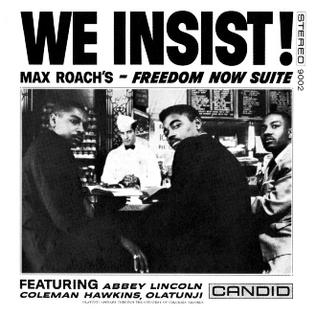

Seminal recordings came into my ears, not chronologically: Charles Mingus’s bitter burlesque, “Fables of Faubus,” with its catalog of racism-excusing villains of the ’50s; Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit” and Archie Shepp’s “Rufus,” both about lynchings, and both timely, even though they were recorded almost thirty years apart; the Max Roach-Oscar Brown, Jr. protest songs collected in their Freedom Now Suite; Max’s followup collaboration with Abbey Lincoln on “Mendacity,” a song that seemed rancidly cynical then and seems almost casually candid today; John Coltrane’s “Alabama,” a dirge with variations for the four Black girls killed by a KKK bombing in 1963; and – late in my consciousness but antedating all the others – Louis Armstrong’s rendition of Fats Waller’s “Black and Blue.” When I finally came to that recording, I wondered, “How did his White audiences hear the line ‘I’m White inside’ in 1929?”

Seminal recordings came into my ears, not chronologically: Charles Mingus’s bitter burlesque, “Fables of Faubus,” with its catalog of racism-excusing villains of the ’50s; Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit” and Archie Shepp’s “Rufus,” both about lynchings, and both timely, even though they were recorded almost thirty years apart; the Max Roach-Oscar Brown, Jr. protest songs collected in their Freedom Now Suite; Max’s followup collaboration with Abbey Lincoln on “Mendacity,” a song that seemed rancidly cynical then and seems almost casually candid today; John Coltrane’s “Alabama,” a dirge with variations for the four Black girls killed by a KKK bombing in 1963; and – late in my consciousness but antedating all the others – Louis Armstrong’s rendition of Fats Waller’s “Black and Blue.” When I finally came to that recording, I wondered, “How did his White audiences hear the line ‘I’m White inside’ in 1929?”

Only lately have I begun to reflect on what value jazz may have in this moment, in 2020. In a lot of contemporary minds – minds not informed by any deep listening or understanding – “jazz” is an artifact of a bygone time, a punchline to mock fatuous hipness, a catch-all that includes everything from Pink Floyd to Kenny G. The word itself is a problem for a lot of serious musicians whose work springs from that tradition – Henry Threadgill and Anthony Davis have both won Pulitzer Prizes, and neither wants to be limited by being thought of as a “jazz artist.”

And yet. I find that jazz is one of the very few traditions of American art that springs wholly from Black consciousness. Black folk made its rules, and only those White musicians who learned those rules and played by them could ever achieve legitimacy. It is the story of American art with the colors reversed, for once.

As one of my writing heroes, Albert Murray, put it: “Can a white man really play Negro music? Of course he can. If he is a good enough musician and respects the medium as he would any other art form. If he develops the same familiarity with its idiomatic nuances, the same love of it, and humility before it as the good Negro musician does. Why not? But certainly not if he is really ambivalent about it . . . Not if he allows his publicity to convince him that he is superior to the masters he knows damn well he is plagiarizing.”

So, I finally got it, in as much as I ever could get it: if I wanted to feel something of what Black people were feeling – not just in any present moment, but in many moments past – I could find a way to do so with jazz. I could never fully understand – how can anyone fully understand anyone else? – but I could begin.

From there I began to swim against the cultural tide that had so long cast its waves back and forth inside me. Not that the tide ever stayed out – as Kendi warned, the struggle to be antiracist in our society can never end.

While swimming through the tide this summer, I kept hitting the rocks of the phrase “systemic racism,” which struck me as too easy, too simple.

It might give someone a momentary warm glow to think, “I’m better than the system.” But what’s also going on, I think, what’s really pernicious, what poisons souls and twists perspectives, is what might be called “casual racism” – the jokes and snide remarks and assumptions and alarm bells and instant judgments that are all too easy to succumb to when the outside world isn’t looking on. That casual racism is everywhere, and I see it in myself.

Ibram Kendi saw it in himself, in the blanket judgments of White America that he eventually came to set aside. He also realized that it could never be enough to be “not racist.” Aside from systemic change, what he calls for is a personal effort by each of us to see the racism inside ourselves and fight it, to be actively antiracist. The norms of society, the permissions we get from our consciences and our communities to be privately racist, those have to change along with the laws and the customs. In five words, antiracism has to begin at home.

That was some schooling.

Kendi’s lessons were unexpectedly reinforced to me by “Romeo and Juliet in Rwanda: How a Soap Opera Sought to Change a Nation,” a July episode of the always-enlightening public radio / podcast series Hidden Brain, hosted by Shankar Vedantam. The program tracked the genesis of the genocide against the Tutsis in Rwanda in 1994, how radio played a pivotal role in changing the norms of Rwandan society so that violence against neighbors became acceptable, and how a post-war Rwandan radio soap opera called “Musekeweya” was designed to teach lessons of tolerance and restore decency to society.

And, surprisingly, how the lessons the soap opera sought to teach were not learned by its listeners: as Vedantam reported, a study of the soap opera’s listeners demonstrated that their views of themselves and the genocide were not affected by the continuing drama.

Instead, the producers and Vedantam pointed out that the behavior of Rwandans changed over time, even if their underlying attitudes hadn’t. What made the difference was the listeners’ sense that their society no longer found the targeting of Tutsis acceptable. The norms had changed.

Vedantam summarized: “People don’t always do what they believe, but they usually do what they think everyone else believes. . . . The currents that govern human behavior are fickle. If you want to make change and then preserve it, you need to be eternally vigilant.”

To Kendi and Hidden Brain I would only add that cross-cultural communication seems to me to be vital to building a framework of antiracist norms. A quote I love from Martin Luther King, Jr. says it simply and eloquently: “People fail to get along because they fear each other; they fear each other because they don’t know each other; they don’t know each other because they have not communicated with each other.”

For me, jazz has become part of the knowing and part of the communicating. It is like an open hand, extended and ready for another hand in reciprocity.

This summer, I often found my mind’s ear playing the hope-against-hope opening theme from Duke Ellington’s piano concerto, New World A-Coming. The title expresses the yearning felt by Ellington and many others of his Black generation, that true equality could be just over the horizon in 1943 – that things might change once World War II had been won. The music expands on that, at times in celebration, at times with furrowed brow.

Even in the ’50s, after reality set in, Ellington kept playing New World A-Coming, and he kept it in his book.

His solo piano reduction of the piece became part of his First Sacred Concert in 1965, by which time it had become something of a prayer for tolerance in the wake of Malcolm X’s assassination and Bloody Sunday in Selma. That was also the year that the Pulitzer Prize jury recommended that Ellington be awarded a special citation, but the Pulitzers’ oversight board scuttled the idea, because of prejudice against jazz, or just plain prejudice. Duke’s Pulitzer had to come posthumously.

He was still playing New World A-Coming in 1972, less than two years before his death – and as it happens, his lovely recording of it in that year was issued for the first time just three years ago.

I listened to that 1972 recording as I wrote this piece. The optimism is still there, and the promise still unfulfilled.

About the works discussed in this piece:

“Romeo and Juliet in Rwanda: How a Soap Opera Sought to Change a Nation,” July 13, 2020 episode of public radio / podcast series Hidden Brain (produced by Matthew S. Schwartz; edited by Tara Boyle; executive producer: Shankar Vedantam) [https://www.npr.org/2020/07/13/890539487/romeo-juliet-in-rwanda-how-a-soap-opera-sought-to-change-a-nation]

Ibram X. Kendi: How to Be an Antiracist (New York: One World, 2019)

Alice Randall: Black Bottom Saints (New York: Amistad, 2020)

Regina Harlig, Alex Miskho, Aaron Troncoso, Jim Pergolizzi, Conor Dwyer Reynolds, et al., Confronting Racial Covenants: How They Segregated Monroe County and What to Do about Them: A Guide Provided by City Community Land Trust and the Yale Environmental Protection Clinic, 2020 [https://law.yale.edu/sites/default/files/area/clinic/document/2020.7.31_-_confronting_racial_covenants_-_yale.city_roots_guide.pdf]

Ralph Ellison: Invisible Man (New York: Random House, 1952)

Bill O’Brien, “The Pythodd Feeling,” Upstate [Democrat & Chronicle Sunday magazine], September 6, 1970, pp. 4-5 [https://www.newspapers.com/image/136632325]

Art Tatum: “Without a Song” (Vincent Youmans / Edward Eliscu / Billy Rose), rec. July 1955, from 20th Century Piano Genius (Verve CD set, 1996; originally issued on LP in Art Tatum Discoveries, 20th Century Fox, 1960) [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RuJmBDCa7YQ]

Duke Ellington: “Lotus Blossom” (Billy Strayhorn) from . . . and his mother called him Bill . . . (RCA, 1969) [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=elo63IXDGjM]

Charles Mingus: “Fables of Faubus” aka “Original Faubus Fables” (Mingus) from Charles Mingus Presents Charles Mingus, with Eric Dolphy, Ted Curson, Dannie Richmond (Candid, 1961)

Billie Holiday: “Strange Fruit” (Abel Meeropol [pseud. Lewis Allan]), with Sonny White, Frankie Newton (Commodore, 1939) [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gCnZptOn7bc]

Archie Shepp: “Rufus (Swung, His Face at Last to the Wind, then his Neck Snapped)” (Shepp) from Four for Trane (Impulse, 1964) [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gCnZptOn7bc]

Max Roach & Oscar Brown, Jr.: We Insist! Freedom Now Suite, with Abbey Lincoln (Candid, 1960) [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UsvFzXr-o-8]

Max Roach & Abbey Lincoln, with Eric Dolphy: “Mendacity” (Max Roach / Chips Bayen) from Percussion Bitter Sweet (Impulse, 1961) [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZmfJjq63Eyk]

John Coltrane: “Alabama” (Coltrane) from Live at Birdland (Impulse, 1963) [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k8iKZUBDrJQ]

Louis Armstrong: “Black and Blue” (Fats Waller / Andy Razaf / Harry Brooks) (Okeh, 1929; re-recorded for Decca at Symphony Hall, Boston, 1947)

[original: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ghRzenaeKaI]

[Symphony Hall: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RJ_nz_TgTGg]

Albert Murray (editors: Henry Louis Gates, Jr. & Paul Devlin): Collected Essays and Memoirs (Library of America, 2016) (The quotation above comes from p. 114.) Arts Fuse review of Albert Murray, Collected Essays and Memoirs, edited by Henry Louis Gates Jr. & Paul Devlin. Library of America.

Duke Ellington: New World A-Coming (1943) original orchestration (premiere performance), rec. 1943, from Live at Carnegie Hall, Dec. 11, 1943, Storyville, 2011: {https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q_ccM2Er2z0}

solo piano version, rec. 1972, from An Intimate Piano Session, Storyville, 2017: [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pXRsJ__oD2c&list=OLAK5uy_lUuD85xIAvwk9Wnl34X-C7-8bKwsjC3tQ&index=10]

Steve Elman’s more than four decades in New England public radio have included ten years as a jazz host in the 1970s, five years as a classical host on WBUR in the 1980s, a short stint as senior producer of an arts magazine, thirteen years as assistant general manager of WBUR, and fill-in classical host on 99.5 WCRB.

Tagged: Alice Randall, Black Bottom Saints, Frederick Douglass, How to be an Antiracist

I’m glad to read so thoughtful an essay from a long-time and dependable advocate of music and creative expression. No doubt others of us are wrestling with issues of race and privilege and looking for clarity and direction. (Thanks for additions to my reading list! )

Well done, well written by my first Boston friend who I called Ziggy Elman in honor of the Jazzman of the same name. His love of the arts and his exacting attention to detail show through here as we continue to deal with our own silent prejudices while we continue to fight for justice and equality. Carry on.

Thanks, Steve, for such a superb, thoughtful essay-memoir. For me, the epiphany moment as a white boy growing up in Columbia, South Carolina, was having a friend turn me on to Monk’s Brilliant Corners. Oh, how that music, turned up high, filled up my friend’s living room!

Steve this is a literary musical journey providing a view into a place of a shared awakening of Jazz, and so well documentented. Yours was an artistic education that was experieced in the best way education can be had. Your love and appreciation of the times that can claim these great musicians is a monumental legacy of Black Americans to the world. I truly appreciate your well-tailored piece of American history with so much wrapped up inside the words written so eloquently. Thank you!

Steve, Thanks for tying in so many aspects of the challenges we face in a society not fully willing to confront racism, sexism, ageism and the other myriad biases we hold unaware. As you describe it Jazz knits together our common threads into a unifying picture of what we can do right as one people. The Kendi book helps us understand that actions speak louder than words going beyond platitudes to the active awareness needed to change behaviors.