Visual Arts Commentary: Digital Media — Public Art Is a Bridge to Our New Normal

By Mark Favermann

In a time when every day seems like Wednesday, creative use of new media is a visual and experiential bridge to our new and hopefully innovative normal.

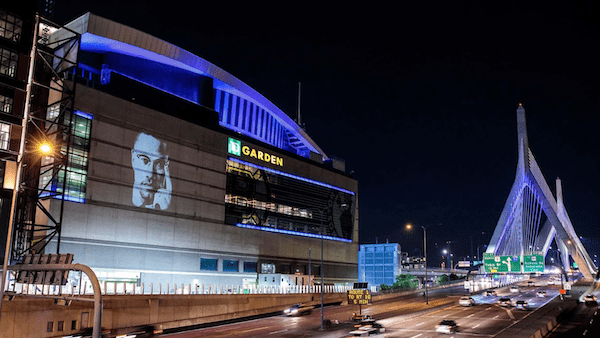

Sam Okerstrom-Lang and Caleb Hawkins, TD Garden with Malcolm X projection, 2020. Photo: Aram Boghosian.

Over the last couple of months Liberty Bell, an augmented reality public art project by Nancy Baker Cahill, was presented consecutively in six cities along America’s Eastern seaboard, including Boston, Charleston, Philadelphia, and Washington, DC.

The piece was inspired by the original cracked Liberty Bell in Philadelphia. It is a line “drawing” that appears to hover above and beyond its viewers. As the image sways and slowly dissolves, it is accompanied by the sound of bells tolling. The tolling becomes increasingly unpredictable and arrhythmic, moving from the harmonious to the atonal and then back to the melodic.

The breakdown of the image’s brushstrokes and the sounds of the bell are symbolic of our moment in history: they represent how the loosely knitted threads of our union are unraveling and then come together again. The piece provides a somewhat awkward but cohesive visual reflection on the evolution and transformation of American liberty over time. The artist chose July 4 as a launch date, to mark the patriotic occasion as well as to advocate for social justice.

A strong example of the use of Augmented Reality (AR), Liberty Bell is impermanent: in fact, it is ephemeral, invisible to the naked eye except for those with smartphones and tablets. Part of the artist’s goal was to stimulate dialogue in the community; the soundtrack features relevant conversations on current events from cultural leaders and community members in all six cities. According to Cahill, “In an age of pandemic, surveillance, injustice, and disinformation, who is actually free? That’s the conversation we need to have.” In Boston, Liberty Bell was set at Fort Point Channel.

In the mode of the Liberty Bell project, AR pieces are being created as stand-alone projects or as parts of a series. Today’s public art is often interactive (changes are triggered by a viewer’s movement or action) and designed to engage (or stimulate) discussion of community and what it means today. AR can encompass a wide range of electronic or digital art, including performance art, digital art, video, animation, specialized lighting, projection art, digital mapping, virtual reality, and organic art forms. Often several media forms are used together. At their best, these artworks succeed at making strong (and active) communal connections with viewers while enriching individual perspectives.

Often deeply involved with technology, nontraditional public art is about more than serving up strikingly contemporary aesthetic experiences. The goal is to nurture civic conversations. This work emanates from not only trained fine artists, but in some cases from technology engineers, software developers, and even curators. The interaction among these various worlds encourages increased access to the latest technology, which suggests that there are no borders to art’s possibilities. AR, for example, expands the scope of public art almost infinitely: it can exist in all sizes and in all spaces, from public parks to building facades to our living rooms. Usually accessed by headsets, Virtual Reality (VR) is a simulated experience that can resemble — or depart completely from — reality. Both AR and VR have intersected with and expanded public art opportunities, a collaboration that will become increasingly fascinating to follow, especially in a pre/post COVID-19 world.

In recent years, a number of stunning examples of nontraditional public artworks have become part of the environmental experience in the Boston area. Acting as a digital plinth, the Rose Kennedy Greenway has served as an outdoor showcase for cutting-edge temporary forms of art. The park continually commissions artworks (featured for a short duration) and sponsors AR projects with Boston Cyberarts and other organizations. In the process, the Greenway has become a patron of the creative use of a wide spectrum of media: it is fostering, developing, and presenting electronic and digital experimental arts.

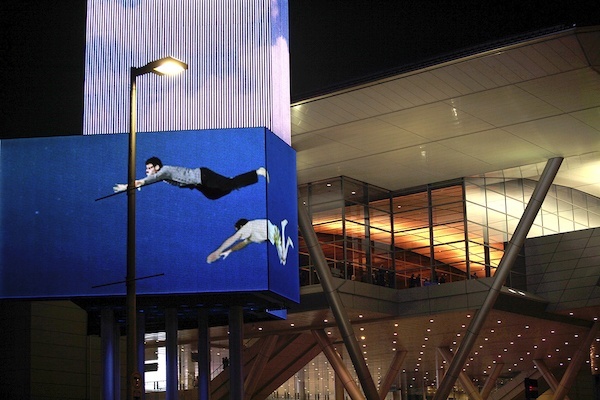

Jeffu Warmouth, “Art on Marquee” at the Boston Convention and Exhibition Center. Photo: Boston Cyberarts.

Since 2012, Boston Cyberarts has teamed up with the Massachusetts Convention Center Authority (MCCA) to create “Art on the Marquee,” a continuing project that commissions public media art for display on the 80-foot-tall multiscreen LED marquee outside the Boston Convention & Exhibition Center in South Boston. It is the largest urban screen in New England, which makes it a unique digital canvas, one of the first of its kind in the US to integrate art alongside commercial and informational content. This important structure is a major component of the MCCA’s long-standing neighborhood art program.

Since 2012, Boston Cyberarts and the MCCA have commissioned over 300 works by Massachusetts artists, thus supporting and cultivating the careers of members of the local new media art community. As an outdoor public art “beacon,” visible for half a mile in many directions, “Art on the Marquee” has continued to thrive in the time of COVID — providing much needed opportunities for artists and for the public to experience visual creativity. Currently, the windows of the Boston Cyberarts gallery (above the Green Street MBTA Station in Jamaica Plain) are showcasing over 30 rounds of artists’ contributions to the “Art on the Marquee.”

The growing digital artist community has developed in many significantly creative ways and directions. A recent project inspired by Black Lives Matter and its focus on social justice was created by Sam Okerstrom-Lang and Caleb Hawkins. Titled “Protest Projections,” this pop-up video installation series was dedicated to raising awareness around the issues of police brutality and Civil Rights. A series of large, monochromatic, high-contrast images were projected onto a number of prominent government buildings, including the Massachusetts State House, Boston City Hall, TD Garden, and Boston’s Edward Brooke Courthouse. The faces projected included Blacks who have been recently killed by police, including George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, as well as significant Civil Rights figures, such as Malcom X and Martin Luther King Jr.

The series highlighted past as well as current racial tensions, protesting the long imbalance of racial power in the United States. These tensions were embodied in the compositional contrast between architectural surface and projected light. The pairing up of faces and sites powerfully juxtaposed the solidity and permanence of the architecture with the ephemeral qualities of the projected images. Viewers were invited to interpret for themselves the meaning of the opposition: passionate voices of the street set against indifferent durability.

In a time when every day seems like Wednesday, creative use of new media is a visual and experiential bridge to our new and hopefully innovative normal.

An urban designer and public artist, Mark Favermann has been deeply involved in branding, enhancing, and making more accessible parts of cities, sports venues, and key institutions. Also an award-winning public artist, he creates functional public art as civic design. The designer of the renovated Coolidge Corner Theatre, he is design consultant to the Massachusetts Downtown Initiative Program and, since 2002, he has been a design consultant to the Red Sox. Writing about urbanism, architecture, design and fine arts, Mark is Associate Editor of Arts Fuse.

Tagged: Art on the Marquee, Boston Cyberarts, Boston Cyberarts Gallery, digital art, Mark Favermann

Digital media used as public art is a revolutionary way to get ideas across. It is very creative and inspiring in many ways. With the project created by Sam Okerstrom-Lang and Caleb Hawkins that was inspired by Black Lives Matter, the project became a way to show and focus on social justice, police brutality against minorities, and Civil Rights. It was a great way to communicate with people and to bring awareness. Digital art is becoming more and more popular with artists and with the public and that’s really changing a lot. There’s careers, there’s courses to teach how to use tools to make digital art, and there’s people eager to make digital art.