Book Review: A.B. Yehoshua’s “The Tunnel” — A Serious Romp about an Aging Brain

By Roberta Silman

Exuberant is the right word for A.B. Yehoshua’s new novel, not only because of the story’s pileup of characters and events, but also for its prose.

The Tunnel by A.B. Yehoshua. Translated from the Hebrew by Stuart Schoffman. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 324 pages, $24.

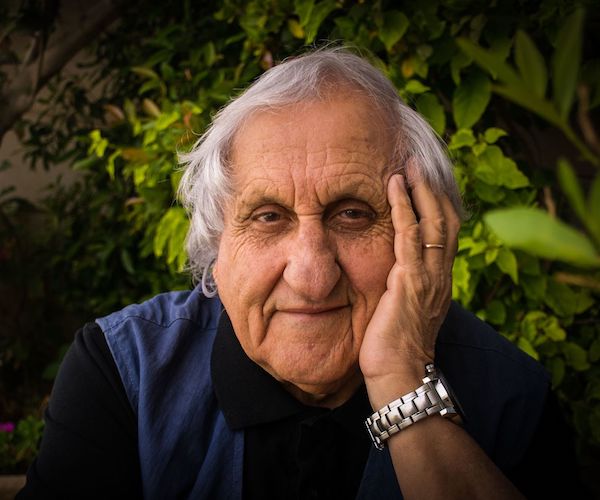

The Israeli writer A.B. Yehoshua is one of the great writers of the 20th century who has, since his early books The Lover and Mr. Mani, been slowly and steadily creating characters of great depth and humor and vision. A man of sly wit and enormous empathy he is exactly what we need in these troubled times. Yehoshua is an especially good creator of women, and The Tunnel is dedicated to his wife of 56 years, Rivka, who died in 2016. Not surprisingly, this new novel is a fabulous portrayal of a long marriage. While it has the serious ballast that is present in all of Yehoshua’s books, it is also a romp that at times reminded me of Britisher Michael Frayn in its appealing zaniness. But perhaps that is the only way to cope with what is going on in the mind of its protagonist.

The premise is simple. Zvi Luria, a retired road engineer, is forgetting things, especially first names. But recently he became confused when picking up his grandson from kindergarten. He started to take a strange kid up to his car, thus causing a ruckus. When he and his wife, Dina, a pediatrician, go to see the neurologist, they discover that there is “mild degeneration” in his brain, but nothing that should prevent him from functioning usefully, maybe even doing some volunteer work, as well as acting on his sexual desires, for “passion is very important for mental activity.” That visit is the line in the sand. After that, everything becomes a test, and we are off and running, mostly inside the wonderfully complicated brain of this once highly successful and still curious and lovable man.

In short chapters we follow him into his car, to the supermarket, to the shuk, while he babysits for his grandson, and, most important, to a retirement party for a former colleague where we learn a lot of his back story. We come to understand that he was a stickler for keeping work and personal life apart, which makes it all the more poignant that the retiring person, whom he resented for deserting his office for a better job in Africa, did so because he had a severely disabled child to support. After that somewhat disastrous evening, Luria’s life opens up and he is suddenly the unpaid assistant to Asael Maimoni, who is, as he tells Dina, “a young road engineer I found working in my old office, planning a secret road for the army near the Ramon Crater” in the northern Negev Desert.

How Luria maneuvers his way through both old and new tasks reminded me at times of Nabokov’s Pnin (one of my favorite characters in all of literature); here one feels the same ineffable tenderness that is the mark of a truly wonderful writer. There are missed opportunities, moments of panic when Luria’s memory fails him, yet also moments of sweet comedy as he and Dina interact or when he gets a tattoo of the ignition code for his car when he realizes he is forgetting more than first names.

But this is more than a story about the dangers of the aging brain. Yehoshua has pulled out all the stops and it is the relationship of Israeli to Palestinian that lies at the heart of this book. For when he and Maimoni go out to survey the road, Luria discovers the secret that is propelling the project and also making it so hard to accomplish. As he confesses to his wife:

. . . the Civil Administration and the security forces, who know everything there is to know about the Palestinians in the West Bank, learned that the wife of this schoolteacher was very sick, heart disease, and only the transplant of a new heart might save her. So Shibbolet, you’ve heard about him, suggested to the schoolteacher to sell Israeli settlers a parcel of Palestinian land, to finance his wife’s treatments and transplant. But the woman, who waited in the hospital for a suitable heart, died before one could be found, and then it turned out that the land sale was a fraud, based on forged documents, and the tormented widower decided to stay on with his family in Israel, fearing what the Palestinians would do to him for tricking them out of land to give to the Jews. And because he decided not to return the money he got from the settlers, he has to hide from the Jews, too, and Shibbolet, who feels responsible for the whole mess, and keeps an apartment in Mitzpe Ramon because his wife has asthma, offered the Palestinian a hiding place in an ancient [Nabatean] ruin on a hill in the crater, which is the hill we won’t bulldoze but instead build a tunnel.

It turns out that Shibbolet has his own military backstory and is also an archeological preservationist with his own agenda. He may also be a metaphor for the complexities that face Israel and how each side’s quest for land is always an issue, yet constantly foiled by the past.

Israel’s A.B. Yehoshua — a writer of sly wit and enormous empathy who is exactly what we need in these troubled times. Photo: Wiki Common.

After Luria tells Dina all this, she comes down with a possibly life-threatening infection, making it necessary for both her and Zvi to spend time in the hospital. When she comes home she dreams up a research project that will take her to a conference in Germany. In the meantime, Zvi goes to a meeting to have his idea for the tunnel approved; by then we are not sure if we are in reality or a combination of memory and/or fantasy. Neither is he. But Luria’s success in having the project approved seems to free him, and when his wife leaves, he embarks on a hilarious and exuberant quest to the site that reflects the absurdity of Ionesco or Beckett rather than the innocent comedy of Frayn.

Exuberant is the right word, not only for the story’s pileup of characters and events, but also for its prose. It has such precision and joy that I would be remiss if I didn’t praise the translator, Stuart Schoffman who can render a sentence like this: “Vaguely distressed, Luria opens the big double window to see if the night has swept away the sun and sprawled across the world.” My suspicion is that the Hebrew is even more satisfying than the English translation, and that we are missing word games and puns, but so be it. What we have is more than good enough — a novel so intimate and vivid that past and present and future merge in ways that generate surprise and delight.

Roberta Silman is the author of four novels, a short story collection and two children’s books. Her new novel, Secrets and Shadows (Arts Fuse review), is in its second printing and is available on Amazon and at Campden Hill Books. It was chosen as one of the best Indie Books of 2018 by Kirkus. A recipient of Fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts, she has reviewed for the New York Times and Boston Globe, and writes regularly for the Arts Fuse. More about her can be found at robertasilman.com and she can also be reached at rsilman@verizon.net.

Did not understand the end of “The Tunnel” By A.B. Yeshoshua

[…] have reviewed The Tunnel, The Retrospective, and The Extra for The Arts Fuse, and I love Yehoshua’s domestic novels which […]