Book Review: “Marking Time” — Documenting the Visual Arts in American Prisons

By Patrick Conway

Marking Time explores how the creation of art in prison can disrupt institutionalized patterns of dehumanization. The book’s larger narrative comes with an overt political aim: “to envision and help create a world without human caging.”

Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration by Nicole Fleetwood. Harvard University Press, 352 pages $39.95

Whenever I mention to someone unfamiliar with America’s carceral system that I teach college writing in prison, I typically get asked one of two types of questions. The most common has to do with my safety. ‘Aren’t you ever afraid something will happen to you?’ Or perhaps the slightly more politic, ‘Is there a guard in the room with you when you teach?’ (My answers, by the way: ‘No’ and ‘No.’) The second type has to do with questioning the quality of students in prison. ‘Is their writing any good?’ or, ‘How do they compare with regular students?’ Some are surprised when I say that student work in prison absolutely compares to that of “regular” students on traditional college campuses. The more technical aspects of their writing may occasionally need attention, but the level of invention in prison often exceeds what I experience from students when teaching on a college campus.

The extent of creativity in prison, particularly within the visual arts, is precisely what Nicole Fleetwood’s wide-ranging new book, Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration, documents. Based upon interviews with currently and formerly incarcerated artists, as well as her own family experiences with incarceration, Fleetwood illuminates the creative process of artists working behind bars. She both documents their artistic methods and practices (or what she defines as their “carceral aesthetics”), as well as their attempts to critique and reconceptualize the brutality of the American criminal justice system. Incorporating the work of artists within several different mediums — from painting and sculpture, to photography and bricolage — Marking Time explores how the creation of art in prison can disrupt institutionalized patterns of dehumanization. The book’s larger narrative comes with an overt political aim: “to envision and help create a world without human caging.”

Much of the artwork included in the collection emerges in direct response to the conditions inside prison. Themes of isolation, the disruption of family, the often debilitating burden of time, and the experience of one’s own removal and erasure from public life are prevalent throughout the collection. One of the more haunting works is Billy Sell’s Self-Portrait (2012), drawn not long before his death after he participated in a hunger strike to fight against the state use of solitary confinement. Officially deemed a suicide by prison staff, witnesses and investigators report that Sell sought medical attention in the days leading up to his death but did not receive it. In the drawing, Sell appears with a shaven head and hollowed, probing eyes behind wire-rimmed glasses. Framed against a black-and-white checkered backdrop resembling prison stripes, he stares directly outward at the viewer, his visage capturing the loneliness, suffering, and fatigue that comes with lengthy isolation.

Beyond thematic trends, another link tying together much of the artwork is the sheer difficulty artists face in the planning and execution of their projects. Lack of physical space, supplies, and the opportunity to create force artists to innovate. “Mushfake” is the term used to describe the process of converting materials acquired in prison — especially contraband — into art. Gilberto Rivera’s An Institutional Nightmare (2012), makes use of shredded state-issued clothing and floor wax he obtained while performing janitorial duties to create art by subverting prison rules. The challenges, however, do not end once the art is produced. Prisons often seize art as contraband, and if artists are fortunate enough to sell their work to outsiders through auctions, the prisons themselves often take a large cut of the proceeds.

Fleetwood’s book highlights how collaborative efforts, self-expression, and the fostering of human connections undergird the value of arts in prison. The arts nurture communities of solidarity within settings that often aim to cultivate dissension and discord. Because prisoners are routinely transferred between facilities, the arts promote opportunities for building relationships and peer education. Often these communities help bridge racial and ethnic divides that threaten to segregate prisons. Art collectives, such as the Fairton Collective (a multiracial group of artists at the Fairton Federal Correction Institution in New Jersey), provide networks of support among artists, both conceptually (in the creation of projects) but also logistically (in the gathering of materials). These networks frequently extend beyond the terms of participants’ incarceration, as artists assist each other in developing and sustaining careers post-release.

Perhaps what is most impressive about Fleetwood’s book is the wide array of artwork included. The artists represent a diversity of backgrounds, as well as aesthetic tastes. Some, such as James “Yaya” Hough and his painting I am the Economy (2018) (which emphasizes how the black prison population is “harshly and mechanically converted into cash by the prison industrial complex”), come with an explicit political message. Others, such as Lisette Oblitas and her Phyllis Porter Place Setting (which honors the victim of a car accident which Ms. Oblitas herself caused) from the series Shared Dining (2015), focus on the redemptive and healing qualities of art. Some are heavily influenced by Western art traditions and the work of “the old masters,” such as George Anthony Morton in Mars (2016), a charcoal portrait of a young black woman. While others rely upon their own ingenuity, like Dean Gillespie in Spiz’s Dinette (1998), a mini-replica of a ’60s Airstream camper covered in cigarette-pack foil and mounted on a frame made from the backs of discarded notebooks.

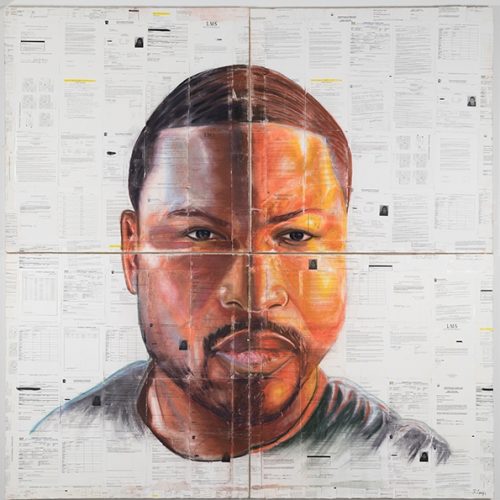

Russell Craig, Self Portrait, 2016. Photo: Stanford.edu.

Fleetwood’s book makes visible the lives, experiences, and creativity of the incarcerated, a population which, despite being over two-million in size, remains largely either ignored or disparaged. Making art becomes a means of survival, a way to fight against the pain and drudgery of serving time. It is fitting that Mark Loughney’s portrait series, Pyrrhic Defeat: A Visual Study of Mass Incarceration (2014-present) adorns the book’s cover. The series comprises nearly five hundred pencil and paper drawings of those who have been incarcerated with Loughney during his time in a Pennsylvania prison. As Loughney puts it, his aim with the series is to draw attention to the sheer number of men and women who are locked away in prison: “The average man on the street probably has not the foggiest idea of what ‘mass incarceration’ means…so my hope is to just get the attention of at least a few.”

The book’s narrative structure is tied together by the abolitionist message of ending human caging. Fleetwood deftly interweaves her own family’s experience with incarceration through anecdotes of two of her cousins to demonstrate how the impact of mass incarceration extends far beyond those who are actually serving out sentences, impacting families and entire communities as well. While Fleetwood makes her cause clear — she wants prisons abolished — her book leaves a crucial question unanswered: what should replace the current system? Perhaps that is outside the purview of Marking Time, but for those familiar with (and bothered by) the current situation it would make sense that imagining solutions would be the next necessary step.

Patrick Conway is a former criminal defense investigator at public defender offices in Washington, DC and Boston, and a current doctoral candidate at Boston College researching the implementation and expansion of higher education programs in prison. His writing has received recognition from the Best American Essays anthology, and an article of his on the involvement of higher education in prison will be included in a forthcoming issue of the Harvard Educational Review.

Tagged: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration, Marking Time, Nicole Fleetwood

[…] Online Arts Magazine: Dance, Film, Literature, Music, Theater, and moreMay 22, 2020 Leave a CommentBy Patrick ConwayMarking Time explores how the creation of art in prison can disrupt […]