Theater Commentary: Why Are America’s Stages Afraid of Dealing with the Climate Crisis?

By Bill Marx

Those who survive the climate crisis will regard American theater’s current indifference with incredulity and disgust.

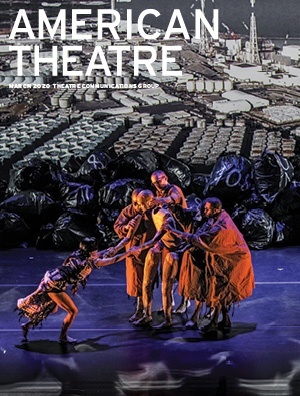

It is unfortunate that American Theatre’s March issue, with its theme of “Theatre & Climate Change,” arrived as the COVID-19 catastrophe dawned. The magazine’s round-up of pieces examine “the ways theatre artists can mitigate the effects of climate change in their work and put their art in the service of advocacy and education. This issue also explores the practical and ethical dimensions of the theatrical response to, and responsibility for, the global climate crisis.”

It is unfortunate that American Theatre’s March issue, with its theme of “Theatre & Climate Change,” arrived as the COVID-19 catastrophe dawned. The magazine’s round-up of pieces examine “the ways theatre artists can mitigate the effects of climate change in their work and put their art in the service of advocacy and education. This issue also explores the practical and ethical dimensions of the theatrical response to, and responsibility for, the global climate crisis.”

The lineup, with links, is below:

-

- A Climate of Change: Lanxing Fu and Jeremy Pickard, the co-directors of Superhero Clubhouse, on how theatremakers are uniquely qualified to lead the way to a regenerative culture of climate justice.

- Digging for New Roots: Playwright Chantal Bilodeau highlights four exciting new works by American theatremakers that focus on climate change and the environment.

- Into the Woods: New Orleans–based writer and theatremaker Amelia Parenteau talks to artists at A Studio in the Woods, a residency in the Louisiana wetlands that preserves the bottomland forest and gives artists the opportunity to connect with nature.

- Have Plays, Must Travel: Mary Rose Lloyd, the artistic director of New Victory Theater in New York City, writes about how TYA companies can offset the impact of international touring.

- Green Theatre: A Reference Guide: A comprehensive list of resources for US theatremakers considering going green, compiled by Alex Durham.

The articles make valuable points about the role theater can play in generating action and inspiring hope. In the words of writers Lanxing Fu and Jeremy Pickard, fighting for “climate justice should be a radical act of love: for the land and the water, for each other, and for the stories we make that will shape our collective future.” So far so admirable, though today’s American theater is anything but radical. Examples of interesting-looking dramas are provided (mainly from small companies); they appear to be relevant visions of the planet’s vulnerability, primarily making their points through compelling imagery rather than dramatic conflicts. (A trilogy from Phantom Limb, which draws on puppetry, dance, and projection, looks particularly striking.) Still, these artistic approaches strike me as somewhat earnest. And American Theatre‘s writers are far too polite (or might that be politically evasive?) when it comes to facing up to the contradictions raised by their rosy assertions about the arrival of theatrical activism. At the very least, there should be anger, concern, even a touch of panic, given our stages’ ongoing anemic response to the climate crisis, which has been pointed out by scientists, with increasing alarm, for decades.

A major (unfounded) assumption is made. Now safely liberated from hierarchical white patriarchy, etc., American theater is supposedly good to go when it comes to tackling the climate emergency. According to Lanxing Fu and Jeremy Pickard:

Across the U.S. we’re seeing a wave of leadership transitions; increased efforts to make inclusive, non-hierarchical spaces; greater recognition of Indigenous rights; equitable pay initiatives; and more productions led by artists rooted in historically marginalized communities. These necessary first steps toward justice are serving to expand and redefine the cultural ecology of U.S. theatre. If the theatre is indeed a microcosm of society, this is good news for climate justice. It means we already have the tools and know-how to build a better world.

But if we have the tools and know-how, why aren’t they being used? And why is it taking so long to put them into action? In her article, Chantal Bilodeau writes that British theater “has been turning out a steady stream of climate-themed plays over the past decade.” How many climate-themed works have been presented in the theaters of America, one of the major energy-gouging countries in the world — particularly in our large, well-funded stages? Is it any surprise that, given the economic stakes, that it is pretty well nada? Bilodeau even admits it, noting the bad news delivered in a HowlRound article, which “looked at U.S. world premieres in the the 2019-20 season at 75 member theatres of the League of Resident Theatre and the 32 National New Play Network core member theaters … exactly zero percentage of plays had climate change or the environment as a thematic focus.” Bilodeau calls this stat “depressing,” before reassuringly citing the arrival of a few “exciting new works.”

But the omission, at a time the climate crisis is accelerating, is much more than depressing — it is a disgrace. And no one in American Theatre asks the obvious questions: WHY HAS SO LITTLE BEEN STAGED? WHY HAVE SO MANY—ARTISTS AS WELL AS CRITICS—REMAINED SILENT ABOUT THIS RELUCTANCE? Isn’t the danger of life on earth going extinct dramatic enough? Playwrights from Sophocles to Brecht would have eagerly sunk their teeth into the theatrical possibilities posed by melting tundra and dying forests. It is hard not to suspect that the neglect reflects political/moral cowardice: in the same way we look back with regret at theater’s decades of silence regarding crucial issues of diversity, gender, and race, those who survive the climate crisis will regard American theater’s current indifference with incredulity and disgust.

Photo: Climate Change Theatre Action.

So, why is there so little theater on the climate emergency in our larger theaters? Partly because of the stranglehold on our theater of the domestic sphere. The “political” is dismissed as self-righteous breast-beating. Also, the American Theatre writers refer (a bit) to the domination of large corporations, but there’s little serious consideration given to their connections with arts funding and how those cozy links may curtail creative independence. As renewable energy advocate Bill McKibben points out, many of the big banks (and universities) that support major stages and other cultural activities — Wells Fargo, J.P. Morgan, Chase Bank, Citibank, and Bank of America — invest heavily (billions and billions) in the fossil fuel industry. The 401ks of theater audiences (and the coffers of major universities) draw on the muscle of the fossil fuel industry — including its considerable political clout on the right and the left. Because of its gargantuan wealth, big oil can afford to speak out of both sides of its brand — it advertises a cuddly, green-friendly commitment to clean energy on MSNBC while, at the same time, doing its methodical best to suck every drop of oil out of the ground. That may explain, at least in part, the climate emergency stalemate on our major theaters. On the one hand, our “inclusive, non-hierarchical spaces” are not going to produce musicals that hail fossil fuel companies as chums of the planet, battling against the Green Warriors. But neither will they present dramas that draw a bead on how and why the world’s oil companies aid and abet global decay — cultural, spiritual, and environmental. Or works that examine the passionate conflicts within the environmental movement: there are clashing ideas about how we can save the planet.

Of course, preachy, self-righteous dramas that only flatter the egos of the enlightened are not what’s called for. One way out of that impasse is for theater artists to create brave new worlds. Here is Bilodeau on that challenge:

So while making theatre about climate change may indeed mean stories about oil extraction and deforestation, sea level rise and extreme weather events, it really means creating a new root metaphor for our lives — a new worldview. We artists and creators are being called upon now to imagine the story that could shape the next millennia. Ours should be a golden age of theatre, an explosion of new voices and stories, of bold forms and theatricality, of explorations of deep time and interspecies relationships, all buoyed by a renewed passion for breaking all the old rules.

All well and good, but the mythological setup sounds passive to me. Can’t drama actively combat the complacency that paralyzes us now (as it has for decades)? Some of the old rules should stay: because they emphasize the struggle that had been (and is) an integral part of our embracing the truth and reality of climate change. William Blake’s “Without contraries is no progression” underlines the kind of theater I am thinking of: it is a vision of perpetual conflict rather than settling for a resolution via “root metaphor.” The climate crisis is generating countless clashes that we are not seeing on our stages. Could that be because dramas of that sort would challenge audiences about the decisions they are making (or not making) today? I have raised one example — the legitimate tensions among those trying to figure out the best ways to combat the climate emergency. These dilemmas are not easily resolved.

Another limitation: the tone of the American Theatre articles (as well as the “exciting new work” mentioned) comes off as uniform. Why not ridicule both sides of the climate crisis coin — the hell of global degradation and the heaven promised by our liberation from fossil fuels? The rebellious study Bad Environmentalism: Irony and Irreverence in the Ecological Age examines a wide range of cultural forms — theater, video, film, performance art, and literature — that draw on ambiguity, irreverence, subversion, and blithe disdain to lampoon the “good citizenship” bromides of “mainstream environmentalism, corporate greenwashing, and political co-optation of environmentalist rhetoric.” Anarchistic, satiric theater, via an amalgamation of comedy, drama, and music (“The Climate Crisis Follies”), would be an effective way to cleanse away the mind-fogging, obfuscating cliches sold by “green” hucksterism. And why not more scripts that draw on the speculative power of science fiction to create utopias and dystopias?

My hope is that as American theaters grapple with the COVID-19 crisis they will ask themselves the kinds of questions Boston’s Handel & Haydn Society posed itself about its “core existential purpose: why are we here? What do we do, and why does it matter?” May the soul-searching lead to some stage work that confronts a global crisis that is not being slowed down by the virus. (Some argue that it is accelerating destructive forces.) This will be theater that sobers, provokes, delights, and compels: performances that will dramatize the risks and rewards of fighting for the health of the climate in the future. Protecting life on the planet will demand radical changes in our lives, spiritual as well as economic. American theater should encourage those changes as it dramatizes the conflicts they generate.

Not all theaters will go that way. No doubt the larger stages that survive the financial catastrophe will continue to cater to the privileged, grinding out “inspirational” fare, perhaps for the anemic ghost of Broadway. But smaller theaters, nimble enough to meet social distancing restrictions, will arise across the country. My dream is that they will aid and abet the necessary transformation in consciousness, which means they will not flinch from presenting tragedy. There are no assurances we are going to be able to mitigate the harm that we have done. Margaret Klein Salamon, in her excellent book Facing the Climate Emergency, argues that moving from a passive acceptance of death to becoming active climate warriors will mean “acknowledging the truth of our climate and ecological emergency, grieving the past and the future that has been lost.” (Aristotle redux — theater’s confrontation with elemental fear and pain will generate catharsis). We need theater artists with the courage to follow an agonizing path. It is one that, as Sophocles knew, reaches down to the roots of our blindness. It is only then that we will know what to do — once we can see.

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of The Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Tagged: American Theatre Magazine, american-theatre, Climate Crisis

[…] How many climate-themed works have been presented in the theaters of America, one of the major energy-gouging countries in the world — particularly in our large, well-funded stages? It is any surprise that, given the economic stakes, that it is pretty well nada? – Arts Fuse […]