Book Review: “The Planter of Modern Life” — A Biography of an Agricultural Visionary

By Roberta Silman

Here is a splendid biography from which you will learn things you never suspected, a book that will renew your faith in passion and what Louis Bromfield called those peculiarly American traits: integrity and idealism.

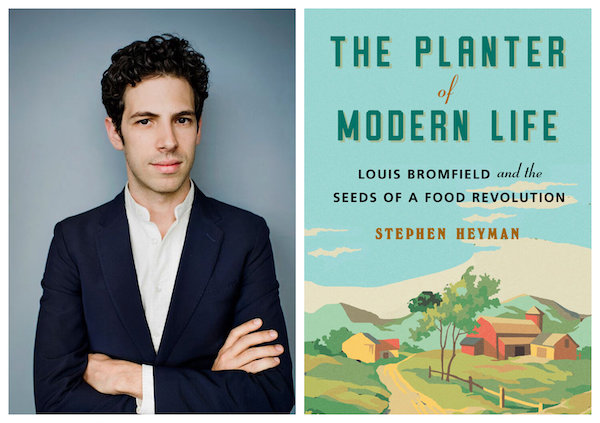

The Planter of Modern Life, Louis Bromfield and the Seeds of a Food Revolution by Stephen Heyman. W.W. Norton, 340 pages, $26.95.

A biography of Louis Bromfield? He had been a household name when I was a girl but he had disappeared into the firmament not long after his death in 1956, the year I graduated from college. The only thing I could remember about him was that he wrote a slew of books that sold very well, and had won the Pulitzer Prize for a novel in 1927 when he was a mere 31 years old, that Hemingway and Fitzgerald both thought he was second-rate while envying his fame and sales. And maybe something about strong ties to Hollywood where several movies were made of his novels. Yet here was my friend, Matt Tannenbaum, owner of The Bookstore in Lenox, MA, insisting that I read it.

I am so glad I did. The Planter of Modern Life is a wonderful book, filled with surprising and fascinating details about a life consumed by two passions: writing and farming. It is also exactly the sort of book to read right now, when we are stuck in our homes, and, if we are lucky, watching the landscape grow greener and thinking about starting our own gardens. And also thinking about our food supply in ways we may never have thought about it before. For Bromfield was an agricultural visionary, an important forebear of the environmental movement that includes sustainable agriculture, rotational grazing, and organic farming. Like his younger contemporary, the great Frenchman Andre Voisin (whom, oddly, Heyman does not mention but whose work with grass and its relationship to health was seminal after World War II, and whom I know about through my son Joshua, who studied plant and soil science at the University of Vermont in the ’80s), Bromfield and his work gave rise to such figures as Rachel Carson, Allan Savory, Joel Salatin, Wes Jackson, and Wendell Berry, among many others.

In his Introduction, Stephen Heyman writes:

As much as Bromfield’s story is a biography of a person, it is also a biography of a landscape — or, rather, two landscapes. The first is the garden he built in interwar France. This began its life as a literary salon of unusual distinction. But it became a kind of field laboratory, the place where he discovered — with a little help from his French peasant neighbors, and a little more from his literary gardener friends like Gertrude Stein and Edith Wharton — how to collapse the distance between literature and agriculture, how to put his love of the land on the page. The other landscape is Malabar Farm, which he established in 1939 in Richland County, Ohio, halfway between Cleveland and Columbus.

It was a “hybrid life,” filled not only with the soil and manure but also with literary and Hollywood gossip and complicated family relationships and close friends and unrealistic, sometimes grandiose, ambitions — all revolving around a man determined to live life to the very fullest.

We first meet Louis in France where he is an ambulance driver for the American Field Service during the First World War. He is tall and fit and a little awkward, but engaging. He is also aware of the economic realities, having had to leave Cornell after only a semester studying agriculture because of a reversal in his family’s fortunes. He makes another try at college, studying journalism at Columbia, but by January 1918 he is in Europe where he witnesses a love of the land, especially in France where every inch of soil was cherished, that will inform his life thereafter.

After World War I he heads to New York, determined to “be a writer,” hangs around the Algonquin Hotel, marries a socialite five years his senior, Mary Appleton Wood, and in 1925 goes to Paris where he does his stint as an ex-pat with Hemingway and Fitzgerald, attends the legendary parties at Ford Madox Ford’s, and begins friendships that eventually lead him to luminaries like Gertrude Stein and Edith Wharton and Edna Ferber. Children start coming — eventually three daughters — and he discovers he can tell a story even though he is far from a natural writer. So there are novels, lots of them, and by the time the third one, Early Autumn, wins the Pulitzer prize in 1927, his name is everywhere. He decides to move to Senlis, 30 miles north of Paris, where there is a “colony of American bon vivants,” and where he creates his first great “garden” on a scale of what most of us would call a small farm. In addition to his growing family is a personal secretary, a mysterious and eccentric man named George Hawkins, and a Scottish nanny, Jean White.

After World War I he heads to New York, determined to “be a writer,” hangs around the Algonquin Hotel, marries a socialite five years his senior, Mary Appleton Wood, and in 1925 goes to Paris where he does his stint as an ex-pat with Hemingway and Fitzgerald, attends the legendary parties at Ford Madox Ford’s, and begins friendships that eventually lead him to luminaries like Gertrude Stein and Edith Wharton and Edna Ferber. Children start coming — eventually three daughters — and he discovers he can tell a story even though he is far from a natural writer. So there are novels, lots of them, and by the time the third one, Early Autumn, wins the Pulitzer prize in 1927, his name is everywhere. He decides to move to Senlis, 30 miles north of Paris, where there is a “colony of American bon vivants,” and where he creates his first great “garden” on a scale of what most of us would call a small farm. In addition to his growing family is a personal secretary, a mysterious and eccentric man named George Hawkins, and a Scottish nanny, Jean White.

Although Heyman has done his homework and reports reliably on all the literary gossip involving Louis during his time in France, and the endless parties with myriad celebrities and the drinking and the poker games, as well as an interminable dinner with the Duke of Windsor and Wallis Simpson, his book comes most alive when he is exploring Louis’s extraordinary love for a way of life that is almost gone. Drawing on Louis’s autobiographical “novel” The Farm, which is more memoir than novel and was written in France and published in 1933, he gives us the story of Louis’s forebears and their fundamental beliefs. Heyman tells us that Louis’s dedication “explained that this story was not only a record of the self-sufficient pastoral world that his grandparents built but also a call to recapture it.” Then he gives us Louis’s words:

“The Farm” is the story of a way of living which has largely gone out of fashion, save in a few half-forgotten corners and in a few families which stuck to it with an admirable stubbornness in spite of everything . . . It has in it two fundamentals which were once and may be again intensely American characteristics. These are integrity and idealism. Jefferson has been dead more than a hundred years and there is no longer any frontier, but the things which both represent are immortal. They are tough qualities needed in times of crisis.

After writing The Farm Louis could somehow see more objectively what he was doing at Senlis. “I moved my family to France so we could love a genuinely American life,” he said, truly prescient words in light of the political winds blowing across Europe.

In a beautiful chapter called “Blight” which begins with Louis’s affection for the dying Edith Wharton and which intertwines passages about the beauty of dahlias with Louis’s political views, we learn that in the midst of all the frantic work of farming and party-giving, he was beginning to sort out where he stood in the ever more frightening political landscape. Taking a stand against both Franco and Hitler early on, he did all he could to convince Americans of the threat of fascism. During the Spanish Civil War he was in charge of the Emergency Committee for American Wounded, described by American news organizations — not all favorable — as “the Bromfield Group.” Heyman informs us:

In all, the committee helped more than 1,000 Lincoln Brigadiers make their way home. For his work on their behalf, Bromfield would eventually receive the French Legion of Honor. But something broke in him after Munich.

By late fall 1938 the Bromfields headed for home.

But before we get to Part Two of this biography, Heyman takes us on a diverting detour about Louis’s love for India, the trips he took there to see the Maharaja and Maharani of Baroda (his poker partner), the knowledge he gained from the Indian agricultural community, especially the work of Albert Howard at his soil institute in Central India (a short course in what was then called the “organic school of farming”), as well as the details he gathered to write his book The Rains Came. The novel’s success continued after it was made into a movie in 1939, a great year for Hollywood. The novel and film enabled him to buy the farm in Mansfield, OH, which he called Malabar after the hills above Bombay Harbor, one of the first sights he had had of India. And about which he said, “Nothing could be more appropriate than giving the farm an Indian name because India made it possible.”

The second half of this book is informative, uplifting, and, in the end, heartbreaking. He fell in love with a place with poor soil (he had bought it when it was under snow); transforming it into a fertile working farm was far easier said than done. He had no idea how to make such a venture viable, let alone profitable. He lacked the ability to dig in (literally) and ended up choosing farm managers who were sometimes capable and sometimes not. He planned ahead based on money not yet earned — often from his increasingly slapdash books. His political position before Pearl Harbor added complications: he tried to convince the powers that be in Washington that America had to go to war. Life for him had become a constant struggle. He also fancied himself an architectural authority and immediately wanted extensive renovations to the original farmhouse. The parts about him and his architect Louis Lamoureux are hilarious — especially to anyone like me (married forever to a structural engineer) who is familiar with the almost inevitable war between architect and client.

Eventually the house got finished, the outbuildings became useful, and the farm became not only far more fertile than anyone had reason to hope, but also beautiful, fulfilling his ambitious dreams for it. Because of that Louis deluded himself for a long time that things were going just fine, saying,

My travel, my experience — nothing I have ever done has given me nearly as much satisfaction as this bit of land and what we have been able to do with it. I take deep pleasure in going out every morning and seeing the miraculous changes which have happened, and which are happening, and which will go on happening until the end of our lives.

There is no denying how much he loved the farm; as evidence Heyman devotes an entire chapter called “Four Seasons at Malabar” based on the Farm Journals from 1944 to 1953. And he loved the people who flocked to it, friends from Europe and Hollywood and New York who loved his company, his hospitality, his generosity, and the beauty he had created. One of the things Malabar was most famous for was that it was where Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall had their bucolic wedding in 1945.

But by the early ’50s all was not well in Paradise. The books Louis wrote about farm life were filled with “exaggeration, sentimentality, sloppiness, repetitiousness, and pretentiousness — especially pretentiousness.” Critics were not kind; the books still made money, but never enough to cover the expenses Louis had. And, although Louis had become a well-known figure, warning politicians in Washington about the dangers posed by new pesticides, his personal life was suffering. George Hawkins died suddenly of a heart attack in 1948, the eldest daughter Anne had issues and was never going to be self-sufficient, the marriage which had had its ebbs and flows was clearly ebbing. And he was drinking and smoking too much.

But by the early ’50s all was not well in Paradise. The books Louis wrote about farm life were filled with “exaggeration, sentimentality, sloppiness, repetitiousness, and pretentiousness — especially pretentiousness.” Critics were not kind; the books still made money, but never enough to cover the expenses Louis had. And, although Louis had become a well-known figure, warning politicians in Washington about the dangers posed by new pesticides, his personal life was suffering. George Hawkins died suddenly of a heart attack in 1948, the eldest daughter Anne had issues and was never going to be self-sufficient, the marriage which had had its ebbs and flows was clearly ebbing. And he was drinking and smoking too much.

Strangely—because he had been a champion of the Jews before and during World War II and clearly had many friends who were Jewish—Louis could not accept his daughter Ellen’s choice of Carson Geld, a Jewish boy from Brooklyn who wanted to help him make Malabar the farm it could have been. Louis made life difficult for them and then, even more strangely, he turned on Hope and her husband, who was gentile. Was the farm, as his daughter Ellen thought, “too precious to him, too much an expression of himself, to risk its sharing”? Or was he so disappointed in himself he couldn’t accept help? Or was he beginning to feel the effects of the Multiple Myeloma that would eventually kill him at the far too young age of 60 in 1956?

We will never know. Both his daughters, who had married men interested in farming, eventually left Malabar and ran their own farms, Ellen and Carson going far away to Brazil. After Mary died in 1952, Louis was alone. Although he had a brief friendship with Doris Duke, who had sought his advice about her own farm, he spent the last two years at Malabar still writing books that might help him make ends meet. To no avail.

Louis Bromfield died in March 1956. Every paper in the United States carried his obituary, the New York Times on the front page. He was clearly bigger than life, and his accomplishments as a writer and a farmer were praised; so were his abilities as a raconteur and a host. But here was an example of one of my mother’s favorite phrases, “How the mighty are fallen.” Bromfield’s name fell quickly out of the literary landscape, and his hopes that Malabar Farm would become a research center were never realized. Moreover, until this splendid biography, only a handful of people have known the full extent of his contribution to what is now called the food revolution.

So here is a book from which you will learn things you never suspected, a book that will renew your faith in passion and what Louis called those peculiarly American traits: integrity and idealism. It is not a story with a happy ending, but it feels necessary and very American during this challenging time. We are lucky, indeed, that Heyman decided it was a story worth telling, and we must be eternally grateful that he has told it with such authority and breadth and compassion.

Roberta Silman is the author of four novels, a short story collection and two children’s books. Her new novel, Secrets and Shadows (Arts Fuse review), is in its second printing and is available on Amazon and at Campden Hill Books. It was chosen as one of the best Indie Books of 2018 by Kirkus. A recipient of Fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts, she has reviewed for the New York Times and Boston Globe, and writes regularly for the Arts Fuse. More about her can be found at robertasilman.com and she can also be reached at rsilman@verizon.net.

The book title is familar. It reminds one of Constantin Guys, Ernest-Adolphe-Hyacinthe-Constantin, a Dutch-born Crimean War correspondent, water color painter and illustrator for British and French newspapers. Charles Baudelaire called him the “painter of modern life,”

Thanks for this. As i look out over the green line car barn i can have a virtual perambulation through farm and foresight.