Arts Commentary: WBUR’s Clogged “ARTery”

By Bill Marx

Every organization in the Barr Foundation’s charmed circle — large arts groups and The ARTery — has a financial stake in reinforcing the belief that the Barr’s money is being put to supremely successful use.

Nov 19th Arts Criticism confab (l to r:): Kathryn Boland, Dance Magazine; Zoë Madonna, Music Critic, The Boston Globe; Jameson Johnson, Editor-in-Chief, Boston Art Review, Ed Siegel, Critic-At-Large, WBUR; Maria Garcia, Senior Editor, WBUR’s The ARTery; and Front Porch Collective moderator Pascale Florestal. Photo: David Costa.

A trenchant article (posted on December 5, here is the link) in the Boston Business Journal raises important questions about threats against the independence and credibility of local arts criticism. As writer Don Seiffert puts it, “Two of the Boston area’s largest local news sources — WBUR and The Boston Globe — are getting hundreds of thousands of dollars in grants from the Boston-based Barr Foundation. It’s bringing a raft of potential conflict-of-interest questions. How do newsrooms avoid bias, or even the appearance of it, when covering organizations that also get money from the same philanthropies funding that coverage?”

WBUR’s ARTery has a particularly large barge floating its way. I am quoted a few times in the BBJ piece, challenging the online arts magazine’s decision to use theater critic Rosalind Bevan to review stage productions in a community that she is a part of. Bevan has been affiliated with a number of local troupes; at the moment, she is a “producing/casting apprentice” for the Huntington Theatre Company. She has also worked (and may so again) with The American Repertory Theater and Company One. (She tells BBJ that she has “joined the latter group’s Season Planning Committee.”) All of these companies are (or have) received funding from the Barr Foundation. ARTery is funded to the tune of hundreds of thousands of dollars by the Barr Foundation. This crisscross of cash raises serious issues regarding the fairness of the magazine’s arts criticism.

In her contributor’s ID posted on the station’s website, Bevan is referred to as a “director and theater practitioner.” No mention is made of the specific local troupes she has and is currently working for. Why not? Could be that someone at the ARTery knows that it won’t look kosher to readers and the theater community if names were named? To me, it is a sign of guilt. As is the ARTery’s relative lack of transparency (an issue raised by Seiffert) when it comes to letting readers know when stage companies under review have received funding from the Barr Foundation and/or have employed Bevan. For instance, Bevan was Assistant Director for Company One Theatre’s production of Greater Good. The favorable ARTery review (by Carolyn Clay) neglected to inform readers of this fact. (Given my argument, I will supply some transparency * of my own at the end of this commentary.)

I believe the ARTery‘s decision is harmful for arts criticism and the arts, and not only because it raises conflict of interest issues. Of course, one reason I am speaking out so forcefully is my fear that if the ARTery’s arrangement is normalized it will give permission to other media outlets to do the same. If this practice became routine at WGBH, The Boston Globe, and elsewhere, arts criticism would be neutered, transformed into a species of faux-marketing or a tool for career advancement in the theater community. Beyond this injury to the integrity of criticism, the ARTery‘s bad behavior ends up reinforcing the staid status quo. It curtails, rather than encourages, honest and independent judgment.

The traditional editorial restriction for theater critics forbids them from working in the community whose productions they evaluate. The reason is obvious: criticism should be free of bias. Political reporters are barred from employment in the DNC or RNC; sports writers are not allowed to be paid by the teams they cover. These professional guidelines apply to covering the arts — a reviewer or arts reporter needs to be seen as honest and credible, professionally distanced from those they judge. At least that is the goal if your standards are set by The New York Times, The Washington Post, the Boston Globe, and other major newspapers and magazines. (I am not familiar with any leading mainstream outlet that is currently using — or has ever hired — freelance arts critics who are active participants in the community they review.) Of course, if your editorial standard is Shopper’s World, the rules are more … flexible. Seiffert asked WBUR’s ARTery Senior Editor Maria Garcia about Bevan’s arrangement and got this response:

Garcia said Bevan “doesn’t review friends or companies that she currently engages with on a professional basis,” and that “currently, (Bevan) is a casting apprentice at the Huntington, so she does not review any Huntington productions.” (Bevan wrote a mostly positive review in July about Tea at Five at Huntington Theatre, but told the Business Journal that she didn’t start working there until Aug. 13).

The rejoinder is painfully clear: what is stopping Bevan from “engaging professionally” with New Rep or the Lyric Stage Company in the future? She can review some of their productions positively now and, after a few months have passed (as with the Huntington Theatre Company), join up with the troupes. And, once Boston’s stage companies notice that ARTery‘s other reviewers are given space to review (nicely) shows Bevan is connected with, well, it seems that it would be a smart move to become her friend. Also, just when did Bevan start discussions with the Huntington Theatre Company about “engaging” with them? Before July, when she reviewed Tea at Five? I am not charging anything — it could easily be a coincidence. But the arrangement OK’d by the ARTery inevitably generates suspicions, particularly in a theater community that is increasingly desperate for media coverage.

[Correction: The Huntington Theatre Company informs me that Tea at Five was not an HTC production — the Huntington Avenue Theatre (one of the company’s two venues) was rented for the pre-Broadway try-out. Happy to have that clarified, though it does not undercut my argument about the ARTery‘s lack of transparency and Bevan’s conflict of interest issues. She still can become engaged in the future with any of the stage companies she critiques. And each season the HTC employs a number local actors, directors, and designers — members of the Boston theater community that Bevan may be called on to review for the ARTery.]

Apparently none of these problems have occurred to Garcia. Or they are discounted as the price of doing critical business. As she told Sieffert:

“Having theater practitioners review plays on a freelance basis for a journalism institution is not new or unprecedented,” Garcia said in an email. “It’s a reality necessitated by the urgent need for informed and diverse theater critics and by a lack of full-time theater jobs around the country.”

What are the names of the major mainstream outlets who have hired, on a regular basis, freelance critics who are active participants in the area they cover? I won’t bother with Garcia’s absurd second point — why should the “urgent need for informed and diverse theater critics” mean that ethical corners have to be cut? As for the lack of full-time theater jobs around the country, that is sadly true. But freelance critics come cheap — I was one for over two decades, so I know all too well. Why not take some of the Barr Foundation lucre and put it to good use? Make Bevan a full-time theater critic? Or, if that is not feasible, pay freelance arts critics juicy fees for their work? Many reviewers would grab at that opportunity. (It is not as if WBUR is hiring expensive investigative reporters.) As I have argued in other columns, the truth is that the accelerating disappearance of arts critics is not a matter of money. Cries of poverty are a face-saving red herring. We don’t have freelance arts reviewers because the mainstream editorial powers-that-be don’t want them. Reviews don’t generate sufficiently high web traffic. What is preferred is guaranteed uplift: supportive, informative, and positive features, interviews, and commentaries, etc., that will please fat cat donors, the arts community, and the Barr Foundation (for example). Everyone is happy — and no one is challenged.

Finally, in response to Sieffert’s suggestion that someone might just perhaps think that something sorta fishy is going on, Garcia retorts that there are the delusional among us:

At the same time, Garcia acknowledged that some readers could perceive the potential for bias, saying, “Could someone see there are the optics (of a conflict of interest)? Sure, but it’s not rooted in reality.”

But what if some stage artists, those not part of the blessed Barr Foundation-ARTery nexus, believe something is wrong? Won’t some troupes feel left out of the food chain? Is she dismissing these fears as unreal? In fact, there are members of the theater community who are alarmed by the ARTery‘s arrangement with Bevan. But objectors are reluctant to speak out because of the magazine’s (and NPR station’s) huge media clout. Does anyone want to take the chance of alienating Bevan or Garcia? Dare to query their exculpatory optics? No way … not if they yearn for invaluable NPR coverage. So, predictably, resentment and anger will fester over time. And once the ARTery gets away with ignoring the obvious conflict-of-interest issues raised by Bevan (as it looks like it will), we can look forward to even more embedded arts critics. A Boston Globe reviewer will be “professionally engaged” with the Nora Theatre Company; the WGBH freelance theater critic will toil part time for the Lyric Stage Company. This is a surefire recipe for bias, unfairness, and chaos. And it will mean the end of credible arts criticism. Perhaps that is The ARTery‘s ultimate goal?

Which brings me to my broader point. I attended a November 19th conference on Arts Criticism hosted by the Front Porch Collective. Among the speakers were Ed Siegel, former editor of The ARTery, and Maria Garcia. Note: the proceedings were videotaped by HowlRound, a free platform for theater-makers, which has received a “sustainability” grant (hundreds of thousands of dollars) from the ubiquitous Barr Foundation. In the BBJ, Andrea Hickerson, director of the School of Journalism and Mass Communications at the University of South Carolina, has this to say about the Barr’s strategy of covering all the bases: “‘From the Barr Foundation’s point of view, it’s pretty genius,’ she said. However, she added, ‘It makes them look greedy.’”

The confab served up the usual bromides about arts criticism — no money for critics, the need for a variety of reviewing voices, etc. Trickier issues, among them what critical authority means today (if anything) and the lack of editorial interest in the fate of arts criticism, were ignored. For me, the most interesting speaker was easily the Boston Globe‘s classical music critic Zoë Madonna — she supplied bits of gritty reality rather than slaphappy clichés. I was highly amused to hear Siegel referred to as a “legacy critic.” That makes me one as well. But some old soldiers seem content to fade into the woodwork. Other “legacy” critics, like yours truly, are going to battle against the deconstruction of theater criticism.

Garcia spoke about the need for diversity and for criticism as self-expression — all laudable goals. But what took me aback is when she said the ARTery wanted to post pieces that were “disruptive.” Have you ever read anything in the ARTery that could be described as close to being disruptive? What rose-colored “optics” are these? Calling for diversity or restorative justice via the arts in the bluest of blue states is not going to unsettle anyone. It is routine talk in polite liberal circles. Praising a whole lot of what is going on in the arts is not going against the grain.

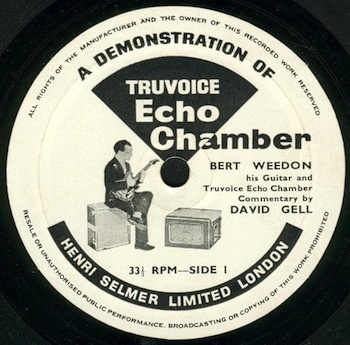

Frankly, criticism of local theater, in the ARTery as well as in the Boston Globe and elsewhere, has become homogenized, predictably moderate, and safe. It is anything but disruptive. Unlike writing on politics, economics, and sports, arts coverage is more often than not boring. Why? Could it partly be that the Barr Foundation, by funding the media and arts organizations, has created a self-perpetuating tape loop (a plush echo chamber?) of unquestioned admiration, guaranteed appreciation? After all, who wants their big bucks from the Barr Foundation to end or to be cut back? Every organization in the Barr’s charmed circle — large arts groups and the ARTery — has a financial stake in reinforcing the belief that the Barr’s money is being put to supremely successful use. In this context, there can be no genuine “disruption” because that would mean ignoring what the Barr Foundation calls its “overarching goal” — “to elevate the arts and enable creative expression to engage and inspire a dynamic, thriving Massachusetts.” Does healthy skepticism, edgy criticism, and reportorial investigation fit into the Barr’s call to create a “dynamic, thriving” cultural conversation? Not really, at least there’s little evidence of it in the media’s anemic coverage of Boston’s arts scene.

Frankly, criticism of local theater, in the ARTery as well as in the Boston Globe and elsewhere, has become homogenized, predictably moderate, and safe. It is anything but disruptive. Unlike writing on politics, economics, and sports, arts coverage is more often than not boring. Why? Could it partly be that the Barr Foundation, by funding the media and arts organizations, has created a self-perpetuating tape loop (a plush echo chamber?) of unquestioned admiration, guaranteed appreciation? After all, who wants their big bucks from the Barr Foundation to end or to be cut back? Every organization in the Barr’s charmed circle — large arts groups and the ARTery — has a financial stake in reinforcing the belief that the Barr’s money is being put to supremely successful use. In this context, there can be no genuine “disruption” because that would mean ignoring what the Barr Foundation calls its “overarching goal” — “to elevate the arts and enable creative expression to engage and inspire a dynamic, thriving Massachusetts.” Does healthy skepticism, edgy criticism, and reportorial investigation fit into the Barr’s call to create a “dynamic, thriving” cultural conversation? Not really, at least there’s little evidence of it in the media’s anemic coverage of Boston’s arts scene.

As I noted in an interview with the author of the provocative book Du Bois’s Telegram: Literary Resistance and State Containment, journalists routinely follow the money in politics. “But what about the arts? When it comes to culture, the popular assumption is that philanthropists, corporations, and governmental organizations are neutral or idealistic players, funding imaginative projects dreamed up by artists and institutions. But can we make this assumption so easily?” The question is worth asking, and some enterprising reporters (outside of Boston) are beginning to probe the unhealthy connections between big money and the arts. Michael Massing just had a cutting piece in the New York Times about “How the Superrich Took over the Museum World.” The depressing result? “… dependence on the kindness of billionaires comes at a price. Today’s museum world is steeply hierarchical, mirroring the inequality in society at large.” Because of the glaring gap between the haves and the have-nots, gargantuan banks and educational institutions, hand in hand with the 1 percent, fund the arts as a way to airbrush their tainted images — selling themselves as deep-pocketed friends of a “dynamic” and “thriving” culture. (Or would that be economy?) The mega-bank Wells Fargo, for instance, is one of the country’s major arts funders. Yet, along with evidence of its criminal business practices, the bank also invests millions in the fossil fuel industry and private prisons. Should artists, arts lovers, and critics care? Or is this just the price of sustaining show business?

I think they should at least consider the matter. Uber-rich individuals and institutions tend to resist systemic change, particularly when it comes to the problems of the climate crisis and income inequality. (Note the sour reaction of the moneyed classes to Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders.) Theater companies are adept at sensing the trip wires around the donor class’s “comfort zone”; they steer clear of churning up any troubling waves. Is it any surprise that so few stage productions examine the entitled world of those who profit from the degradation of the environment or the politics of poverty? (I would argue that our theater companies, like the besieged natural world, need to be decorporatized and rewilded.)

But things might be changing, at least in terms of generational push back against the prerogatives of the wealthy. Gen Z is connecting the dots as it protests in the streets against overgrown banks (Wells Fargo among them) and large educational and financial institutions who use the arts as talcum powder to sprinkle over their destructive blemishes. And that gives me hope that out of today’s riled-up teens will arise the fearless arts critics (and supportive editors) of tomorrow, aesthetic activists who will celebrate the arts as a means of delight and instruction — and resistance. Which, in the name of truth, beauty, and the survival of humankind/animalkind, may well mean biting the well-heeled hands that feed them and the arts.

*Transparency

WBUR

I was a freelance theater/arts critic at WBUR from 1980 to 2006. In 2000 I was hired full time and asked to create and edit WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. My weekly column for the publication was a finalist for an Online Journalism Award in 2005. When the station let me go in July of 2006 the magazine was deep-sixed.

I became a full-time lecturer in Boston University’s College of Arts and Sciences Writing Program in 2007. I won a CAS award for excellence in undergraduate teaching in 2013 with the late Anthony Wallace. I began teaching a class on arts criticism at BU’s College of Communication five years ago. I attained the rank of Senior Lecturer and retired from the Writing Program last year, but I continue to teach my class on arts criticism. Like The Arts Fuse, the seminar is a labor of love.

I started The Arts Fuse in 2007. I am proud of what the magazine and its many writers have accomplished. And I feel strongly that at WBUR I would not have had the opportunity to come close to building the Fuse‘s editorial breadth, depth, and independence. Things worked out well.

I have been writing and reading arts criticism for many decades and I care deeply about the craft of reviewing and its future. As I have asserted often, criticism plays a vital social role: it is one way in which the value of the arts is articulated. WBUR has the resources to do better by its arts coverage, as does WGBH and The Boston Globe, both of whom I have sharply critiqued on this issue as well.

Barr Foundation

The Arts Fuse has never received funding from the Barr Foundation. The organization contacted me in 2013. I met three times with a Barr representative over the next two years — the last session was in 2015. The magazine was regarded positively, but discussions ended after I was told that — given its annual budget of around $20,000 — the Fuse was far too modest an organization for the Barr Foundation to fund. My takeaway: Small is Beautiful.

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of The Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Tagged: arts coverage, Boston-Business-Journal, criticism, Don Seiffert, Maria Garcia, Rosalind Bevan, the ARTery

Not mentioned in the BBJ article about foundation funding for arts critics is the fact The Boston Globe‘s music critic, Zoe Madonna, who sat on the panel referenced above, has been subsidized by foundations (that’s not a typo: its plural) for her position as a Globe music critic. To quote the paper on 10/31/16:

“Amid all the gnashing of teeth over the future of news media, a bright note: The Rubin Institute for Music Criticism, San Francisco Conservatory of Music, and Ann and Gordon Getty Foundation are teaming up with the Globe on an initiative that might just serve as a new model for supporting arts journalism. With funding provided by the San Francisco-based organizations, Zoë Madonna, who won the 2014 Rubin Prize in Music Criticism at the Institute, starts a 10-month post as classical music critic at the Globe…”

Please note that the original funding was for “10-month post” but has now gone on for over two years. If this is a “new model,” and let’s say the Globe has to retrench union writers and editors, does Madonna get to keep her job? And why has 10-months turned into an open-ended funding?

There’s a lot of greed going on here, and it seems unfair to other writers and editors.

The word “retrench,” regarding The Boston Globe‘s treatment of the Boston Newspaper Guild, the union that represents the paper’s editorial employees and many on the business side as well, is far too polite. According to reporter Maria Cramer, the former vice president of the Guild, the paper’s contract negotiators are trying to “whittle down the union to oblivion.”

Thanks for publishing this. But . . . wasn’t this self-dealing obvious from the moment Garcia went after the IRNEs and basically cleared the field of any pesky individuality? I know a corporate initiative under cover of “diversity” when I see one . . .