Arts Commentary: “Counterculture in Boston 1968 – 1980s” — High and Heady Days

By Tim Jackson

About the post-Reagan era, Boston Phoenix and Boston After Dark editor Arnie Reisman observes: “Everything went to sleep, and while we were sleeping, the Republican Party grew six more heads.”

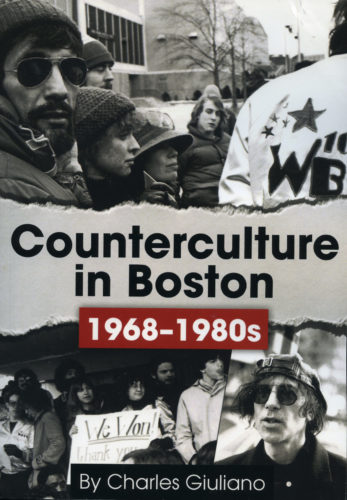

Counterculture in Boston 1968 – 1980s by Charles Giuliano. Berkshire Fine Arts, LLC, 442 pages, $25.

I came to Boston in 1971 after three years in Providence, determined to make something of my fledgling music career. The city was obviously the place to be. I had read about the Lyman “Cult'” in Rolling Stone Magazine, the music at the Boston Tea Party, and learned of Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert’s consciousness-expanding LSD odyssey. There were protests and free concerts on the Cambridge Common.

I came to Boston in 1971 after three years in Providence, determined to make something of my fledgling music career. The city was obviously the place to be. I had read about the Lyman “Cult'” in Rolling Stone Magazine, the music at the Boston Tea Party, and learned of Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert’s consciousness-expanding LSD odyssey. There were protests and free concerts on the Cambridge Common.

I packed up my old Toyota, hitched up a U-Haul, and headed north. My girlfriend, Suzanne (now my wife), and I had to pretend we were married in order to rent a caretaker’s cottage on Hosmer Street in Marlborough. We dived into changing times. We worked with Father Robert Drinan to elect George McGovern and with Daniel Berrigan against the Vietnam War, listened religiously to WBCN, read the new alternative rags called the Boston Phoenix and Real Paper and went every week to the Orson Welles Cinema. She slithered into a miniskirt to wait tables and sing at Timothy’s Too in Framingham. We soon moved to Newbury Street and paid $225 a month in rent. I drove a cab and began playing all the Boston clubs: Jacks, Brandy’s, Gladstone’s, The Oxford Ale House, Bunratty’s, the Inn Square Men’s Bar, and then Paul’s Mall, Passim, the Rat, the Space, The Paradise, Spit, and many others through the years.

These memories came flooding back reading Charles Giuliano’s book, Counterculture in Boston 1968 – 1980s, which chronicles those high and heady days. Twenty interviews with some of the key movers in music, radio, and alternative journalism chronicle how Boston became a hub for writers, musicians, and entrepreneurs in the booming youth movement. Institutions like the Cambridge Phoenix, the Boston Phoenix, the Real Paper and a slew of jazz, folk, and rock clubs, and free concerts — together with the soon to be ubiquitous “American Revolution” on WBCN — led the charge. But don’t be fooled — their pages are about more than nostalgia. After 50 years, many of the interviewees may now be nearly forgotten, but they provide valuable testimony about how Boston’s vitality helped cultivate a significant shift in American culture. Perhaps they offer a map for a resurgence.

On October 26, I heard of the passing of the Freddy Taylor, who ran the Jazz Workshop and Paul’s Mall on Boylston Street. He booked acts from Miles Davis and Herbie Hancock to Muddy Waters, BB King, and even Lily Tomlin. I performed there with Tom Rush on New Year’s Eve in 1977 and with an act opening for Bob Marley and the Wailers in 1973, which was recorded by WBCN. Later, the group opened for Little Feat for a full week of shows. Taylor went on to book for Sculler’s Jazz Club and later concerts at Beverly’s Cabot Theater, where I was sitting when I heard about his passing. Giuliano interviewed him, and also includes an interview from 2011 with George Wein, who ran jazz at the Storyville nightclub, starting in 1950. Wein went on to found the Newport Folk and Jazz Festivals. As a teenager, I saw such performers as Son House, Mississippi John Hurt, Pete Seeger, Eric Von Schmidt, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Sonny Terry & Brownie McGee, and Doc Watson in a weekend at the folk festival. Wein and Taylor were pioneers at widening the appeal of jazz and folk, exposing essential American music to a generation of students from Brandeis, Boston University, Harvard, and other area colleges.

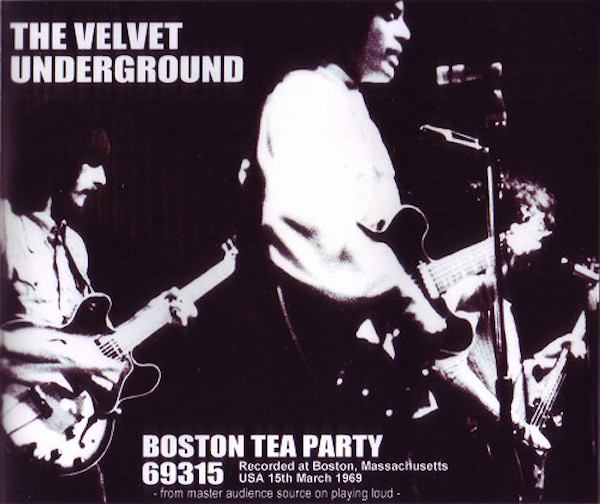

Ron Della Chiesa, interviewed by Giuliano, was an on-air personality at WBCN when it was a classical FM station in the early ’60s. He went on to become a well-known classical music broadcaster. Under the leadership of Ray Riepen, WBCN hit the air in 1968 as the first alternative rock and roll FM station. It was Riepen who also opened the Boston Tea Party and bankrolled the Cambridge Phoenix. It is good to see him in Giuliano’s lineup; his significant influence on the burgeoning counterculture scene is often overlooked. He is at the core of Bill Lichtenstein’s new film WBCN and the American Revolution. Lichtenstein, the book’s first interview, sets the stage for the changes in Boston’s political landscape, as well as for the new forms of radio programming that started up during these years. In addition to talking about BCN’s history of free-form playlists and notorious music personalities, Lichtenstein reminds us of Boston’s legacy of progressive politics and leftist professors: “There were people like Noam Chomsky and Howard Zinn.” As Danny Schechter (known as the “News Dissector” on WBCN, and who went onto a distinguished career in journalism before his death in 2015) proclaims in Lichtenstein’s film, “Boston was a battleground.” The filmmaker elaborates, “We didn’t have room in the film, but Daniel Ellsberg was in Harvard Square at 3 a.m., Xeroxing the Pentagon Papers.” In terms of the era’s activism, archivist David Bieber suggests that “the sixties” really began with the assassination of John Kennedy — and died with the end of the Vietnam war.

There were numerous underground, alternative, and music papers in and out of circulation during these years: Broadside, Avatar, The Cambridge Phoenix, Boston After Dark, The Real Paper, the Boston Phoenix. Harper Barnes, the editor of The Cambridge Phoenix, recalls the impressive number of writers and artists who cut their teeth in these papers: rock writers Steve David and Jon Landau; film critics Janet Maslin, James Isaacs, Stuart Byron, Stephen Schiff, and Gerald Peary; and the wickedly funny theater critic Arthur Friedman. Our Bodies, Ourselves, the feminist guide to women’s health and sexuality, began as a Cambridge Collective. The Whole Earth Catalogue, the counterculture magazine that featured essays, articles, and products about self-sufficiency, ecology, and alternative education, was published as an occasional magazine from 1968 through ’72.

In addition to bands like The Who, Led Zeppelin, and The Velvet Underground, who performed regularly, there was a significant folk scene emanating from Club 47 and Passim. Boston’s best band of the late ’60s, The Remains, just missed national fame. The Barbarians had a few hits, but had too much of a “garage band” sound to make it really big. Rock music was branded as “The Bosstown Sound,” and that turned out to be an inept marketing ploy. The failure of that “sound” to take hold tainted Boston for years until J. Geils, Aerosmith, Boston, and the Cars came to prominence. The new wave and punk scene in the late ’70s and early ’80s — in clubs like the Rathskeller and The Channel — also helped bring vibrancy back to the Boston scene.

Guilano’s primary focuses regarding Boston’s counterculture are journalism and music. But they were part of a larger arts scene. There is a brief mention of David Wheeler’s Theater Company of Boston which, from 1963 to 1975, nurtured a cadre of actors that included Al Pacino, Robert DeNiro, Dustin Hoffman, Robert Duvall, Jon Voight, and others. The MIT Film Unit under the late Ricky Leacock from 1969 to 1988 inspired filmmakers Robb Moss and Ross McElwee. The cinéma vérité and Direct Cinema movement that Leacock championed also influenced Albert and David Maysles (Gimme Shelter) and D.A. Pennebaker (Don’t Look Back). There are only glancing references in the book to the Institute of Contemporary Art, which started up in 1973 — it occupied a former police headquarters at 955 Boylston Street for 33 years. The ICA presented exhibits by Warhol, Bridget Riley, Jasper Johns, Chicago Pop artists, and many others who came to prominence in the late ’60s.

Cover of the first issue of “Avatar” (1967)

With all this amazing activity going on, why has Boston’s underground history been given so little credit? The crash and burn of the Bosstown Sound didn’t help, but interviewees speculate on other possibilities: a transient college population, Boston’s innate conservatism, the chill of New York’s shadow, and San Francisco’s growing mystique, established via its “Summer of Love.” Bieber also suggests that there was a lack of nurturing connections among Boston musicians: too much of what existed was fostered by commercial interests.

Several other books also recount those lively days of change and rebellion. The best may be Ryan H. Walsh’s Astral Weeks: A Secret History of 1968 (Arts Fuse feature), a colorful companion to Giuliano’s interviews. Beyond telling the story of Van Morrison in Boston, Astral Weeks covers the riveting tale of Mel Lyman and his cult-like Fort Hill commune, and refers to Avatar, an underground newspaper. Carter Allen has a book on the history of WBCN called Radio Free Boston. Published 20 years ago, Fred Goodman’s The Mansion on the Hill: Dylan, Young, Geffen, Springsteen, and the Head-on Collision of Rock and Commerce offers a detailed look at how the music business was transformed during this period. As for the experiments of Harvard professor Timothy Leary, T.C. Boyle’s (2019) novel Outside Looking In proffers some fascinating insights.

Overall, Counterculture in Boston will serve as a primary source for understanding the impact and business dealings of the arts during those two decades. For Boston boomers, this volume will trigger plenty of déjà vu. For younger readers, the conversations show what united action can accomplish in a turbulent era. The volume also suggests just what went wrong. The underground youth movement, which yearned for permanent change in a corrupt and unjust political and economic system, was ultimately defeated. Why? The so-called hippie culture became commodified. In his 2019 book It Came From Something Awful, author Dale Beran explains:

This co-optation didn’t end with the hippies but rather inaugurated a mad half-century in which an ever-expanding mainstream consumer culture chased down and trapped the countercultures that harassed it. Each time a counterculture was snagged, it was then transformed, like a vampire, into a soulless husk that served the enemy.

Today, the drift into fantasy, comic book heroes, video games, virtual realities, and social media traps the young in expensive, consumerized niches. Self-reflection leading to protest is not the goal. Maybe that passivity is a defense against the world’s madness, the shattering of the American Empire, and the consequences of a poisoned planet. About the post-Reagan era, Phoenix and Boston After Dark editor Arnie Reisman observes: “Everything went to sleep, and while we were sleeping, the Republican Party grew six more heads.” The voices of the now-aging veterans of the culture wars from the ’60s are proof that, with diligence, nerve, and imagination, dreams of meaningful change may still be possible.

Tim Jackson was an assistant professor of Digital Film and Video for 20 years. His music career in Boston began in the 1970s and includes some 20 groups, recordings, national and international tours, and contributions to film soundtracks. He studied theater and English as an undergraduate, and has also has worked helter skelter as an actor and member of SAG and AFTRA since the 1980s. He has directed three feature documentaries: Chaos and Order: Making American Theater about the American Repertory Theater; Radical Jesters, which profiles the practices of 11 interventionist artists and agit-prop performance groups; When Things Go Wrong: The Robin Lane Story, and the short film The American Gurner. He is a member of the Boston Society of Film Critics. You can read more of his work on his blog.

Nice story. Just want to say that Paul’s Mall/Workshop were on Boylston St., not Newbury.

Tim Jackson is correct in stating that there was more to the arts during the era covered in my book. As I stated the fine arts deserves its own book. It is my plan to write Boston Fine Arts: Museums, Galleries and Artists. The chapter with Arnie Reisman discusses the significance of theatre as the review notes. My book was intended as an oral history and primary source for further discussion and publication. This extensive review, with a generous focus on Jackson’s own experience and career, demonstrates how Counterculture in Boston may serve as a scholarly and anecdotal resource,. It felt important to capture the voices and spirits of this selection of primary sources while that was still possible. I like Jackson’s suggestion of reading this book in tandem with Astral Weeks and other books listed in my extensive bibiograophy. Hopefully my book will encourage Jackson and others to publish their own memoirs and insights.

Great article, Tim, and I definitely need to read this book, as a latecomer to Boston arriving in 1978 to become film critic for The Real Paper. Was James Isaacs ever a film critic, as listed here, or only a music critic? I would add in a bunch more film critics of worth who wrote in Boston: Owen Glieberman and “the Davids.” Yes, let me be the first to note that being named David was essential to writing film reviews in Boston in the 1970s: David Rosenbaum, David Chute. David Denby, David Thompson, David Denby. Amazing, hun?

And lest we forget a bit later, but notable in Boston from 1976 to 2004, the late David Brudnoy.

Boston has a history of radicalism not only in the popular arts of the period under review. More than a century earlier, New England Transcendentalism ushered in radical thought and individualism that continue to inspire. Also, there was the American Revolution. A broader context would perhaps lend substance to the books under discussion.

Wonderful piece, Tim! This is a subject that’s near and dear to my heart, since I’ve written about it before, and it’s part of the reason for my wistful tone when I tell people down here in LA what Boston’s like.

Great stuff, Tim! I certainly hope you are writing a memoir. I’d like to hear about the various qualities and motivations for those 20+ bands you’ve worked with, along with your own aesthetics. (I tried to push Jerry Goodwin to write something but he said no. Perhaps you and he could do something?) All the best!

anything about Harvard Square in the book (other than Passim’s and Orson Welles)…that was the place to hang out for the day with all the book stores (new and used), record shops, movie theaters, food, etc.