Short Fuse: Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Applies the Corrective

By Harvey Blume

In an interview I did with Henry Louis Gates, Jr. in 1997 (for the now defunct “Boston Book Review”), we talked, naturally enough, about the issue of race in America, and about Gates’s sense of mission, as scholar and writer, in relationship to it. One thing in particular that he said sheds light on and in a sense foretells his reaction to Sgt. Crowley twelve years later in that massively publicized Cambridge incident:

In an interview I did with Henry Louis Gates, Jr. in 1997 (for the now defunct “Boston Book Review”), we talked, naturally enough, about the issue of race in America, and about Gates’s sense of mission, as scholar and writer, in relationship to it. One thing in particular that he said sheds light on and in a sense foretells his reaction to Sgt. Crowley twelve years later in that massively publicized Cambridge incident:

There are a million and one things more important to me than my blackness. If, however, I am driving through Lexington, like I was last night at 11:30, going a little bit too fast, and I see a police car, the first thing I think about is that I’m a black man.

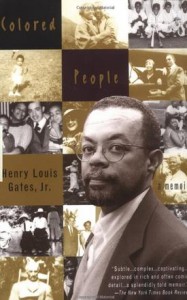

The occasion for the interview was the publication of Gates’s memoir, “Colored People.” And now that the shouting about Gates and Crowley has died down a bit, it seems like a good time to revisit some of Gates’s stands on the Civil Rights Movement, black nationalism, and anti-Semitism.

**********************************************************************

We need something we don’t yet have: a way of speaking about black poverty that doesn’t falsify the reality of black advancement; a way of speaking about black advancement that doesn’t distort the enduring realties of black poverty. I’d venture that a lot depends on whether we get it.

(Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and Cornel West, “The Future of the Race”)

HB: There’s a strong sense in your memoir, “Colored People,” about growing up in Piedmont West Virginia, of how much black people lost in the process of integration.

HLG: Whenever I’d go home on holiday, I’d go up to my cousin Jim’s house. Jim’s a mechanic at the paper mill, very articulate but also very nationalistic. He simultaneously despises white people and fears them. Through him, I understand Farrakhan getting standing ovations. Jim could never voice any kind of rage or reaction to an offense directly to a white person. He’d voice it at home. So you have a catharsis when someone like Farrakhan speaks.

Sometime between 1975 and 1980, I’m talking to Jim and he said, “You know, I think that TJ” — his son — “would have done much better at Howard High School,” which was the black school in our county. Then he said, “We lost a lot because of integration.” We were drinking beer, eating grilled squirrel — yeah that’s rural, we all were raised hunting — and I pressed him. He said, “the first thing is they fired all the black teachers except the principal of the elementary school and the principal of the high school.”

And then there’s what my friend Wole Soyinka calls cultural security. Blacks used to have a cultural base to come out of. The problem was they couldn’t come out of it *to* any place. They never could stand on this base of culture and enter in the larger middle class. They lived and died in a segregated world.

But Jim’s point was well-taken. So I decided to write that world.

HB: “Colored People” recreates and passes on that bygone world.

HLG: My counterparts, between the ages of 35, and 45, say, in positions of authority whether at Harvard or on Wall Street, are trying to maintain access to institutions of power but at the same time be nurtured culturally. I see that coming down all over the country. My brother, a very successful oral surgeon, moved to Madison, New Jersey. Black CEO’s, lawyers, doctors took over that street.

HB: How do you nurture cultural differences in a way that doesn’t fuel racism?

HLG: The beginning is not to think you are determined by one identity. We all consist of multiple identities.

HB: That’s the postmodern take.

HLG: Black people have always been postmodern. Since Dubois coined the metaphor of double consciousness, there’s always a fluid boundary. You weren’t black and *then* not-black. You were black and not-black all the time, always going back and forth. James Baldwin, in one of my favorite quotes, says, “Each of us helplessly and forever contains the other.” Male and female, female and male, white and black, gay and straight — that’s the way it is, no matter what it is.

You define yourself by your work, by your morality, by who you love, the children you father, the money you’ve raised, the books you published, the paintings you painted. There are a million and one things more important to me than my blackness. If, however, I am driving through Lexington, like I was last night at 11:30, going a little bit too fast, and I see a police car, the first thing I think about is that I’m a black man.

HB: It’s tricky.

HLG: Enormously tricky, and not helped by demagogic rhetoric from people who would manipulate us into having one totalized and centralized identity. I tell my kids, you can love Mozart, Picasso, even play ice hockey, and still be black as the ace of spades.

It’s not a novel idea, though it sounds novel when you hear it from a Stanley Crouch, an Albert Murray or a Wynton Marsalis. Until very recently being a Negro was always about that. We were a people raised to assert the presence of the Negro in any endeavor in which human beings were involved.

HB: When did the walls around black identity go up?

HLG: There’s always been a segment of the black community that’s been nationalist — culturally nationalist, politically nationalist, always, from the day in 1619 when the first slaves got off the boat in Jamestown. Still, there’s a paradigm shift in the late sixties. The Civil Rights Movement reaches a climax in the passage of the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act in ’64 and ’65. For 100 years we had said our goal was to get rid of de jure segregation. All of a sudden it’s gone. But everybody goes around mouthing the same rhetoric. It’s like the guy who can’t stop shooting when the battle’s

over.

That particular battle was over. No one had imagined what the next one was.

HB: It’s harder to find language for the next one.

HLG: It’s taken twenty-five years to get people to talk about it. In the meantime, the black middle class quadruples, doubling in the 1980s alone. On the other hand, fully one third of the African American community is worse off today than in 1968. Nobody predicted that outcome. No politics has a solution for it.

![]() HB: You’re saying politics breaks down, can’t scratch the itch. So in comes mythology.

HB: You’re saying politics breaks down, can’t scratch the itch. So in comes mythology.

HLG: I would say it slightly differently. An ideology based on an assessment of the world between, say, 1865 and 1965, after which it no longer describes the world, is transformed into mythology. Simultaneously comes the black power era — black is beautiful, Afros, dashikis, black arts. It’s all very traumatic, King’s murder, the Vietnam war. There never was a time like that. Then affirmative action, to everybody’s amazement, is enforced by Richard Nixon. That’s why the black middle class is bigger. The black middle class wouldn’t be bigger without affirmative action, and there would be no affirmative action without Republican administrations. Irony of ironies but that is the truth.

You get this huge black middle class, relatively speaking, still confronting some forms of racism, with survivor guilt about leaving everybody else home, and all of us conditioned to believe that once de jure segregation ended, everybody would plunge headlong into the middle class. That was the silent assumption of the Civil Rights Movement. But it’s like adding apples and oranges. The two things are not necessarily connected.

So we get a heightening of ideological tension, and the use of mythology to mask class differences. We swathe ourselves in kinte cloth, practice Kwanza, put up Jacob Lawrence posters and photographs of John Coltrane looking out in the distance. We speak more black vernacular than ever and climb in our BMWs wearing bow-ties saying I’m down with the brother.

The rhetoric of separation is higher, and poor black people more isolated than ever.

HB: What do you see as your role?

HLG: I see my role as a continuation of what it meant to be a black person in 1955 when the goal was to establish the presence of people of African descent in every field of human endeavor. I was raised to think in terms of First Negro. Who’s the first Negro to sit down at that soda fountain, the first Negro to try on a shirt in a men’s clothing store? Show that Negro can play hockey, can swim, can play golf. Root for the brother. Integrate that neighborhood. The problem was when we did integrate Lexington or Scarsdale, we missed what it was like back home. You want to go to the local Episcopal Church and sing Anglican hymns or get down in the Ghetto with a gospel choir?

Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

HB: That is a distinctly anti-separatist vision.

HLG: I went to Yale with a class of people recruited through affirmative action. The class of 1968 at Yale had 18 black students, 1.8 percent of the matriculants. The class of 1973, my class, had 96 black students, 7.9 percent. Our goal, as we understood it, was to integrate the higher power centers of America. I still think that’s the way it is. Our goal has to be to see that more black people are brought in to integrate the middle class in America, while we makesure there’s a safety net for those people who don’t get in.

HB: Let me return to the issue of difference. We are educated to think African culture was successfully eradicated in the United States. No African languages survived, no drumming was permitted except for a time in Congo Square in New Orleans, and African religions were supplanted by Christianity. But in “The Signifying Monkey” you write: “The notion that the Middle Passage was so traumatic that it functioned to create in the African a tubula rasa of consciousness is . . . a fiction that has served several economic orders and their attendant ideologies. The full erasure of traces of cultures as splendid, as ancient, and as shared by the slave traveler as the classic cultures of traditional West Africa would have been extraordinarily difficult.”

HLG: The most gratifying sentence I’ve ever written — I’m paraphrasing myself — was that the African slave who sailed to the New World did not sail alone. People brought their culture, no matter how adverse the circumstances. And therefore part of America is African.

HB: Apropos of which, it seems to me that the Yoruban pantheon is displacing the Greek in literature.

HLG: In black literature.

HB: Not only. Also outside black literature. In the William Gibson cyberpunk trilogy, for example, it’s Elegba, god of the crossroads, who is first in cyberspace. Umberto Eco writes about the African gods in “Foucault’s Pendulum” and in his essay on Brazil. The Yoruban pantheon is becoming a focus, a stimulant to the imagination.

HLG: It was one of the most transportable religious and metaphysical systems. There’s something compelling about it that transcends the local. As we become less Judeo-Christian in our search for other systems, I am not surprised the Yoruba are being found.

HB: Also, unlike the Greek gods who are figures of literature only by now, the Yoruban pantheon is still worshipped directly. The Greek gods have been banished to literary Olympus but you can go to Dorchester and a Santeria ceremony where Elegba is being invoked.

HLG: Without a doubt. The difference between the Delphi Oracle and the Ife Oracle is the Ife Oracle is still being consulted every day. It’s alive as a religious system. But, as Soyinka has shown, it has tremendous uses for literature as well.

HB: Let’s talk about your work at The New Yorker. Tina Brown has provided a forum for you to examine black identity in a way that was never before possible in that magazine.

HLG: The number one bestseller in the history of “The New Yorker,” bar none, was the black issue [April 29/May 5 1996]. That’s astonishing.

HB: So you feel “The New Yorker” reaches black people?

HLG: I know it does. The people who made the black issue the best selling number were black; they are people who don’t subscribe and buy it at the new stand.

And I love Tina Brown.

When I was 25, William Shawn asked me to write for “The New Yorker.” I had an audience with him — and I use the term “audience” intentionally. I went to the old New Yorker offices and as long as I sat there I felt like Shakespeare. Then I took the train back to New Haven and I was little old Skip again. Twenty years later, out of the blue, my phone rang. It was Tina Brown. She asked if I could come to lunch. And then she offered me a contract to write six pieces a year.

HB: On subjects of your own choosing?

HLG: I clear it with her but if I want to do it, she’ll let me. These profiles are an entirely new venue and voice for me, a new genre. I can bring to bear literary criticism, my knowledge of African American history and culture. And I love talking to people. I can be scholarly but in a language that’s accessible.

HB: You examine a variety of ways of being African American, up to and including Anatole Broyard’s method, which was to disguise the fact altogether. And your approach is relatively non judgmental.

HLG: Broyard’s widow thought I represented a side of him that shouldn’t have been represented, pertaining not to his racial identity but to what people said about him sexually. Harry Belafonte would have preferred it if I made him more of a statesman. A couple of my friends said they didn’t think I was hard enough on Farrakhan but Farrakhan didn’t think that.

I try to get into people’s style, their mode of being. I am judgmental but try to be subtle about it.

HB: The Farrakhan piece you wrote for the “Times” had two sides. You were taking a principled stand against anti-Semitism, and you were also taking a stand against demagoguery, since that undercut you as an intellectual. I suspect one of your motives in building Harvard’s Afro-American studies department into the intellectual powerhouse it has become is to create another center of leadership and another style of leadership than Farrakhan’s.

HLG: That might be the indirect effect. but the direct goal is so that for my kids and my grandchildren, and for your kids and grandchildren, the academy will include an Afro-American Studies department with as much stature as math or physics. No group of people has been in a position to pull it off before. Harvard is a great place to do it, and this is a great time since there’s a tremendous amount of support from the administration.

I don’t want Afro-American Studies to be deligitimized because of shoddy scholarship or lack of depth. When we launched the “Norton Anthology of African American Literature” last week at the Boston Public Library, I said our generation will be remembered for our success or failure to produce the foundational tools for Afro-American studies. We need to consolidate and codify the intellectual attainments of our people — encyclopedias, dictionaries, concordances, bibliographies, works of scholarship — so that they stand next to he attainments of other people. That, at least, is how I interpret my role. And the “Norton Anthology” gives us a canon.

HB: Isn’t it all little contradictory, at a time when the canon, THE canon, is being picked apart to boast of having an African-American canon?

HLG: You’ve got to have a canon before you get to pick it apart. Once you can take it for granted like air, like your blood, then you can criticize it.

Sure there’s hierarchy. You need hierarchy. If, as a teacher, you can’t explain the difference between Terry McMillan, say, and Toni Morrison — I love Terry McMillan but her fictions are not complex like Toni Morrison’s — then you shouldn’t be teaching. We don’t have the luxury that people in other traditions have of taking thousands of readings of each work for granted. If you’re a professor of African-American literature today, and you write an essay on Phyllis Wheatley, it defines Phyllis Wheatley. It’s not like Shakespeare scholarship. Everything we do is new.

And it is important to remember that what we’re doing wasn’t possible before. You need pockets of blacks in other areas of the power elite for this to happen. We, in Afro-American Studies, are the counterpart to Ken Shanold [sic] and Dick Parsons at American Express, and to Quincy Jones’s in the music industry. Historians will see at us as part of a generation. Whether it’s Wall St., the film industry or Harvard, we are doing the same thing.

HB: You think of your work as thoroughly embedded in history.

HLG: My first degree is in history. If I have had one conscious mission it has been to be part of a group of well-trained black people who want, first, to forever bury the one nigger syndrome, and, second, to end the cycle of reinventing the wheel.

In the past, when you would integrate a place you had one black; that black would never want any competition so he’d keep all the other blacks out. Everyone would thrive in their own little briar patch, and then their work would be gone. There was no continuity, no memory. That’s why I emphasize foundational projects like the Encyclopedia Africana. Consolidate the memory, man, so people stand on that, and don’t have to start all over again.

HB: You are a prolific writer. You move quickly; somehow you avoid getting stuck.

HLG: I write quickly but I meditate on it for a long period, for two months a piece when it comes to my “New Yorker” articles. Then I sit down and do a draft, usually pretty quickly. It’s from a culture of overnighters at Yale. Wait wait wait panic panic panic and then whoooosh.

And then, you have great editors at “The New Yorker.” If I have the confidence, if I know people respect me on the other end of wherever I’m faxing to, and I can just get it down without worrying about looking stupid, that’s a big thing. Every writer I know is insecure. There are only two kinds of writers, the insecure writers who write and the insecure writers who don’t.

HB: You wrote the introduction to the catalogue for the show, “Africa: the Art of a Continent,” that was held at the Guggenheim Museum last fall. That show let African art stand on its own, with an absolute minimum of contextualization. Sometimes African art is reduced to anthropological data; you’ve got to understand everything about how the society works, and don’t have a chance to respond to the art.

But the truth is that African “art” is neither art, in our sense, nor artifact, in the anthropological sense. If you stress the one side, you’re always leaving something else out.

HLG: But we have a century of representations of African art as everything but art. Even black people encourage this myth. Negritude is based on the aesthetic statement by Leopold Senghor that all African art is collectively functional. This idea was picked up by many African-Americans. But the idea that every African sitting there is creating art is bullshit. It was always a specialty. You went to art school; art school was an apprenticeship with a great artist. There was specialization. Not everybody could dance or play the drum.

In the end those objects have to stand as aesthetic statements.

HB: In the case of the Guggenheim show, that worked marvelously.

HLG: But your point is good. I err on the side of formalism. I see it when I write about literature. There is so much sociological and anthropological criticism that I want the formal and aesthetic element brought back. The sublime is a formal manifestation. It’s your eye looking and responding. “Shit, I don’t know what the fuck it is, I can’t even say, but *that* is beautiful.”

HB: The primitivism/modernism thing is twisted and problematic but it contributed to the resonance of the Guggenheim show. Some things looked absolutely contemporary, as if a SoHo artist would give everything to make anything that haunting.

HLG: That’s where we began, other people finding metaphors in the African gods, the Yoruban gods. That’s what universality is. Accessibility. Appreciation of aesthetic virtues on an aesthetic basis. I have always felt, and will probably go to my grave feeling, that attempts to contextualize African art were made primarily because of a doubt about its aesthetic value. So you wrote about everything but.

You could say that the third value I consciously uphold — beside killing the one nigger syndrome, and making it unnecessary to keep reinventing the wheel — has to do with applying a corrective. I try to understand our moment through the lens of history. If, at the end of the twentieth-century, I’m writing about African art, I’m trying to apply a corrective to the past hundred years.

[…] The rest is here: Short Fuse: Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Applies a Corrective […]