Father’s Day Feature: My Father the Former Communist

Having a father in prison meant radical changes in our everyday lives.

In Honor of Father’s Day: an excerpt from an Afterword to the book Cause at Heart: A Former Communist Remembers by Junius Scales and Richard Nickson, recently reissued by Plunkett Lake Press.

— Helen Epstein

(Note: Junius Scales (March 26, 1920 – August 5, 2002) was an American leader of the Communist Party of the United States of America notable for his arrest and conviction under the Smith Act in the 1950s. He was arrested in Memphis, Tennessee, in 1954 after going underground. His appeals lasted seven years and reached the Supreme Court twice. He began serving a six-year sentence at Lewisburg Federal Penitentiary in October, 1961. On Christmas Eve, 1962, President Kennedy commuted his sentence and he was released. — Wikipedia

A Father in Prison by Barbara Scales

In June of 1961, when I am ten years old and living in New York City, my parents –- Junius and Gladys Scales — tell me that something has happened. The Supreme Court has handed down a decision and Papa will have to go to jail. They have not told me about his several trials until now, hoping that I could grow up without anxiety. Now, they can no longer shield me. Not knowing how to feel, I ask questions: why did the judges decide the way they did? Why are they putting him in jail?My father, Junius Scales, was born into a wealthy Greensboro, North Carolina family in 1920. He grew up with deep respect for the Negro staff at his home and was deeply disturbed by the effects of Jim Crow in his community schools and businesses. The Communists seemed to be the only people concerned with civil liberties and labor rights, and issues of social justice. He joined the Party on his 19th birthday, while an undergrad at UNC, Chapel Hill.Junius served in the military during the second world war. After it was over, the Soviet Union — America’s wartime ally — became its Cold War enemy and Communists were viewed as Soviet agents. After Junius graduated from college, he was placed on the FBI’s most wanted list for organizing textile workers in the Carolinas. He was arrested in 1954, then tried and retried until 1961. The Supreme Court finally decided to uphold the lower court decision; he was the only American sent to prison for being a member of the Communist Party, served 15 months of a six-year sentence, was released by President Kennedy in 1962, but never pardoned.

My parents told me that, despite what I might hear, it was not bad to have been a Communist. There were reasons, rooted in deeply-held values and beliefs about how people should be able to live, which had led Papa and yes, Mommy, too, to be members of the Communist Party. Although they wanted me to be proud of Junius, my parents urged me not to tell my friends about my father’s imprisonment, as some of them might not understand and not like me if they knew. So, not knowing who was “on our side” and who was not, I decided not to talk at all.

On October 2, 1961 when my father went to prison, I was in sixth grade.

Having a father in prison meant radical changes in our everyday lives. My mother’s workload increased enormously. In addition to teaching school every day and maintaining a home for me and her aging mother, Gladys led a campaign of friends, well-wishers, journalists, politicians and decision makers, to maintain awareness of my father’s unjust imprisonment. She managed to make ends meet with the help of friends, known and anonymous.

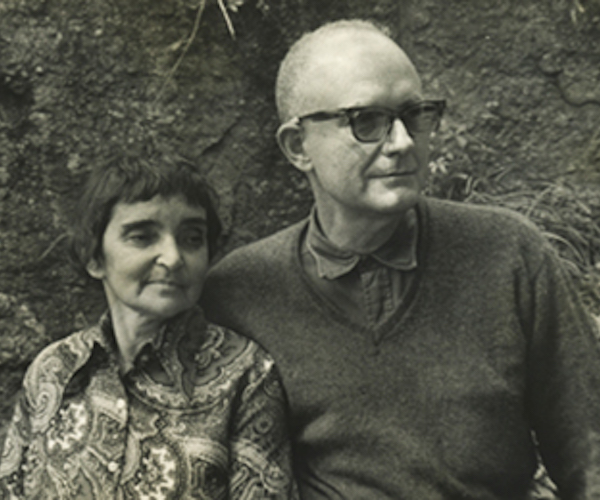

Gladys & Junius Scales, Gladys’ last summer in 1980 – Photo: Barbara Scales Collection.

One Sunday morning, our doorbell rang. Nobody was there but I found a book, The Right to be Different. There was an inscription: “May you know and grow your father’s footsteps.” It told the stories of people who had stood up for truth in the face of persecution from Moses to Jesus to Maimonides to Albert Einstein to Mahatma Gandhi. There was also a bulky envelope, addressed to my mother and stuffed with cash. Not crisp bills from a bank; these were used bills from people’s wallets.

Our visits to Lewisburg Penitentiary were complicated. We were allowed to visit one weekend per month. We drove the two hours from New York through Pennsylvania coal country on Friday, after school. The black mountains of coal slag became my idea of death: nothing would grow on them. Arriving at our hotel in Lewisburg, we passed for visitors to the local college and the staff did not ask questions. On Saturday mornings, we set out early for the prison.

The visiting room resembled a very bare and shabby hotel lobby — with guards. Once the family visitors were seated, the wait for Papa was often long. Once the grey-jumpsuit-clad inmates emerged, gestures and embraces were measured. My mother and father sat on opposite sides of a table and were not allowed to hold hands or touch. I was, however, allowed to hug and kiss, to sit on my Papa’s lap

I was named Best Citizen of my school. In June of 1962, I gave the valedictory address in a pretty dress with thin purple stripes. In September, I entered Hunter College High School. I had recently turned 11. How could I tell my new class mates that I was the daughter of a convict and visited prison once a month? How could I share the unspeakable images from my visits? And how could I explain what had caused him to be there?

I was a good student and learned to enjoy the school which would become a safe haven for six crucial years. It provided connections with remarkable girls, who became remarkable women, but even within that happy and stimulating environment, I was harboring a secret which I dared not share.

Papa came home on Christmas Eve. I had become a pre-teen. He had become an ex-con. My mother was in precarious health. Papa, who longed to teach history to young people, was refused admission by Columbia University Teacher’s College under pressure from the FBI. He worked the late-night shift as a proof-reader at the New York Times and devoted himself to the well-being of his family. He ruminated on how his idealistic efforts had gone amiss and what he could have done differently.

I went to Camp Thoreau, where I met, and embraced, the sons of the Rosenbergs, Michael and Robbie Meeropol, and the grandchildren of Paul Robeson. I learned that other children had suffered painful losses and put my own wounds into a larger context. I learned about the movements that had championed human rights in the United States and around the world.

I longed for and still dream of n escape from that battle zone into which I had been dropped when I was 10 years old. I would like to savor memories of my father without the intrusion of prison walls. I would love to live in a world where the reflexive hatred inspired by the label “Communist,” would dissipate; where prejudices of all sorts would be history and be replaced by curiosity and respect.

In high school, I did a research paper about Scales v. the United States, referencing legal texts and decisions. I was able to see the events that had shaken my life through a legal prism. It didn’t change my life, but it did help me to understand the weight of words and the harm they can inflict. I also learned about a community that existed not just in New York, but in Canada, Mexico and Europe.

I chose to attend university and then to live in Canada where I was able to grow in a way that had seemed almost impossible in the United States. Being in a different country afforded me the opportunity to be myself, to live my own adventures in uncharted territories. If I had stayed in the United States, I might always have been “the daughter of Junius Scales,” and either a pariah or a pitied victim of such a caricature. My own path has led me to work in the arts, bringing performers to a global stage, from Estonia to Tasmania, from Tuktoyaktuk to Oman, from Beijing to Buenos Aires, and across North America. I have been able to spin a modest thread in my dream of a unified tapestry of humanity.

My mother Gladys died in 1981 at 57. In 1988, Junius gave me a hard-bound copy of his memoir, Cause At Heart. He inscribed it to me in a surprisingly formal way:

For Barbara Scales,

This book is my legacy and is the best part of me. To know your father, read it well.

With love,

Junius Irving Scales

I have, in fact, read his book many times. It explains how a scion of a great Southern family turned against the privilege and hypocrisy he saw around him and chose to champion better opportunities for all. It reveals how he set out on a mission, of the disappointments and the challenges he encountered along the way, and how he stood up to overzealous inquisitors. Underlying the telling is the proverbial unanswered question. The very undertaking is the examination of his own life, which is said to make life worth living.

This article is adapted from the Afterward to Cause at Heart by Barbara Scales to be reissued as an e-Book by Plunkett Lake Press this month.

Tagged: Barbara Scales, Cause at Heart: A Former Communist Remembers, Culture Vulture, Junius Scales

My parents were communists and while my father was never imprisoned, we had our own FBI agents, watching us. I attended Kinderland, where Robeson and his family came after returning from Russia.

Would love to meet you and share some memories of our childhoods.