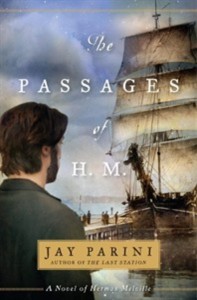

Book Interview: Sailing Through the Mind of Herman Melville

In his novel “The Passages of H. M.: A Novel of Herman Melville” author Jay Parini combines extensive research from existing biographies with a concrete evocation of the nineteenth century writer’s world and mind. We ask the writer a few questions about Melville, and whether there would be a market for his books today.

By Christopher Ohge

The Arts Fuse review of The Passages of H. M.: A Novel of Herman Melville

Arts Fuse: While researching and writing the novel, what impressions of Melville’s personality were you left with?

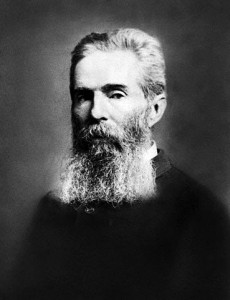

Jay Parini: I was left with the impression that Melville was a troubled genius, possibly a manic/depressive. He may have had too much to drink as well!

AF: In a scene when young Herman thinks about the nature of fiction, the narrator says that “It rendered whatever happened into something utterly fresh and strange. At times, it echoed Truth back to itself in sharper, shapelier tones.” Later on John Troy says, “Everyone knows that the truth can’t be told, not in historical writing.” What does writing a biographical/historical novel satisfy that purely imaginative fiction does not?

JP: With fiction we have a chance to imagine ourselves inside the lives of others. A straightforward biographer is forced to deal with the surface facts.

AF: What does this novel contribute to existing scholarly biographies?

JP: A novel is a grace note, adding nuance, tone, texture, and—perhaps—genuine illumination.

Jay Parini is a poet, biographer, critic, and author of seven novels, most notably The Last Station, which was the basis of an Oscar-nominated feature film, and has been translated into more than twenty-five languages. He is the D.E. Axinn Professor of English and Creative Writing at Middlebury College and the author of Promised Land: Thirteen Books That Changed America.

AF: Did the works of Gore Vidal, who himself stirred the literary world with biographical novels like Lincoln, serve as a model for The Passages of H. M.?

JP: Gore is a friend, a mentor of mine. Yes, his work has been hugely influential on my writing.

AF: Why did you decide to alternate between Elizabeth Shaw Melville’s perspective (“Lizzie”) and a third person narrator in each chapter?

JP: I thought that we needed to get a personal view of H. M., so what better person to choose than Lizzie, his wife of many decades.

AF: Characters in your novel like Robert Jackson exhibit traits of not only Jackson from Redburn but also of Bartleby (when he says “I prefer not to”) and Claggart in Billy Budd. Captains Brown and Pease also seem to have particularities akin to Ahab. Can you describe your motivation in creating certain composite characters in your novel?

JP: I’m trying to get at the sorts of things that might have inspired Melville to write his books. I’m trying to imagine his source material, in other words.

AF: Jack Chase says at one point to a young H. M. that “One can never feel at home in this life. That’s the one thing I believe with absolute certainty. The English language, perhaps, is the only home I know.” To what extent is this is true of Melville himself? In other words, do you see Melville as a proto-Modernist in his rootlessness and fundamental melancholy?

JP: Yes, Melville was certainly a harbinger of Modernist approaches to fiction. Absolutely. He lived in the language itself. That was his real home.

AF: Early in the novel Lizzie speaks of Melville’s famous quarrel with God. After Malcom commits suicide, she believes that “washed in the sorrows of circumstance, lost in the depths of silence,” Melville would never speak again. By the time he writes Billy Budd, Sailor, Melville seems resigned on the question of God. Do you think Melville’s quarrel with God came to an end during his life?

JP: I suspect that he quarreled with God to the very end.

AF: Chapter 12 features an intriguing conversation between Melville and Hawthorne in which they discuss the poetry of the whiteness of the whale, which would eventually appear in Moby-Dick. Do you think that Melville saw his writing as an heir or successor to Hawthorne’s blackness or what he deemed the “great Art of Telling the Truth” in the essay “Hawthorne and his Mosses”?

JP: Yes, he’s responding to Hawthorne here and elsewhere. It was an intense dialogue.

AF: Do you think a novel like Moby-Dick can be written today (without being “damned by dollars”)?

JP: Nobody would buy such a novel today!

=======================================

Ohge on Arrowhead, Herman Melville’s home in the Berkshires

As a writer, I wonder how Melville kept any shred of his sanity—so much talent, so little recognition. And I’m haunted by whatever it was that happened between him and Hawthorne.