Rethinking the Repertoire #1: Camille Saint-Saëns’ Symphony in E-flat, op. 2

It is one of the enduring ironies of classical music that so much of today’s repertoire was written by such a small number of people. This post is the first in a multi-part Arts Fuse series dedicated to reevaluating neglected and overlooked orchestral music. As always, comments and suggestions are welcome at the bottom of the page or to jonathanblumhofer@artsfuse.org.

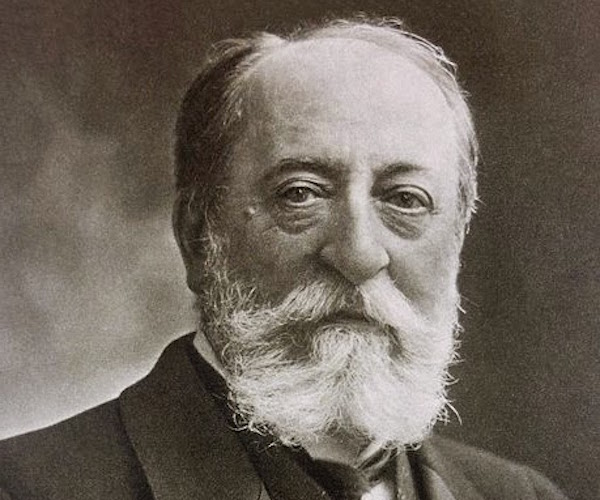

Camille Saint-Saens — one of the most prodigiously talented musicians of his or any other era.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

We begin our survey with one of my favorite musical discoveries of the last three years: Camille Saint-Saëns’ Symphony in E-flat, op. 2.

Saint-Saëns was one of the most prodigiously talented musicians of his or any other era. Born in 1835, he was a formidable pianist who, in his prime, could reportedly play all thirty-two Beethoven sonatas from memory and was highly regarded as an organist, as well. He possessed wide-ranging extra-musical interests (including in mathematics and astronomy) and, like Berlioz, was very well travelled. An almost ridiculously prolific composer, Saint-Saëns’ catalogue boasts over three hundred pieces in all the major genres and forms written over the course of eighty years. Not one of Romanticism’s most original voices, he was one of the period’s greatest craftsmen. Like Ravel, born a generation later, Saint-Saëns revered the art of composition as handed down from Bach, Haydn, and Mozart (especially the latter) and, while his youthful enthusiasm for German music turned to bile during the Great War, there remained, until his death in 1921, a Mozartian clarity to his writing.

This is most evident in the handful of Saint-Saëns’ pieces that remain in the canon: the Second and Fourth Piano Concertos; the wonderful B minor Violin Concerto and the Cello Concertos; the opera Samson and Delilah; the brilliant, witty Carnival of the Animals; and, of course, the celebrated “Organ” Symphony. It’s also true of the Symphony in E-flat.

Saint-Saëns actually wrote five symphonies, two of which (one in A and one in F major, the latter subtitled “Urbs Roma”) went unnumbered. The Symphony in E-flat, published in 1853 as his op. 2, was written between them, when its composer was at the ripe age of seventeen.

Like the work of many youthful composers, it’s to some degree derivative, though it wears its influences proudly. The spirit of Beethoven is never far removed, either in the Symphony’s motivic materials or its developmental procedures. There are dashes of Mendelssohnian brilliance, touches of Berlioz (especially in the orchestration which, in the finale, calls for four harps!), a helping or two of Wagner, bits of Schumann, and a little Gounod, as well.

And yet the cumulative effect sounds and feels like much more than a talented hodge-podge. Certainly Berlioz and Gounod thought so: they were overheard commenting on the score’s merits after its first public rehearsal, not realizing that the teenager sitting nearby them was its composer. It’s also worth noting that, between the premiere of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony in 1824 and that of Brahms’s First in 1874, the genre of the symphony, in the hands of composers like Berlioz, Schumann, and Mendelssohn, was a very flexible thing. Saint-Saëns’ Symphony in E-flat reflects this fact with freshness and confidence. Therein lies a measure of its charm.

On the surface, the Symphony is a fairly conventional, four-movement affair. The first movement follows a traditional sonata form outline; the second (labeled “Marche-Scherzo”) is light and tuneful; the third presents a soaring, lyrical respite; and the finale wraps things up with martial pomp (and a nifty fugue to boot).

But its juxtaposition of contrasting materials and forms keeps it from ever feeling routine or too predictable. One can wax lyrical on Saint-Saëns’ gifts as a melodist but also point out a number of his pieces in which they fail to carry the day. That’s not the case here: this is a Symphony in which just about everything – musical argument, structure, counterpoint, orchestration – succeeds very strongly. Its spectacular coda may not bear the battle scars of Beethoven’s Fifth, but why should it? The purpose of this music is to charm and that’s precisely what it does. Let’s take a closer look to see why.

The first movement opens with, arguably, the Symphony’s most important motive, the interval of a falling fourth. Saint-Saëns presents it right at the start of a very short introduction (just eight bars long) and then elides straightaway into a brisker tempo, in which this interval is elaborated into a lovely, flowing melody. Throughout the entire opening movement, this figure and the rhythmic pattern it’s presented in tandem with – a doubly-dotted long note (either an eighth or a quarter) followed by a short one (usually a sixty-fourth or a sixteenth) and then a longer-held one (a full quarter or a half note) – appear almost obsessively. It’s a Beethovenian technique, for sure, but its appearance in this very different sounding musical context lends it a fresh quality, as do Saint-Saëns’ superior gifts as a melodist: by the time the second theme, bracketed by fanfares, rolls around, we’re clearly dealing with a composer who’s sure of himself, even as he readily acknowledges his most important predecessor in this genre.

Saint-Saëns’ lyrical abilities are nowhere showcased to finer effect in this Symphony than in the two middle movements. The second, called “Marche-Scherzo,” is perhaps the least aggressive march imaginable: its main theme is far more pastoral than militant. Eventually, some dotted rhythms do appear, as does a questing melody in the minor mode underneath a soft, jaunty string accompaniment. Still, the overarching aura of the movement is one of gentility and grace.

Following the sunny second movement comes some of the most pristine, delicate music Saint-Saëns ever wrote. Over a bed of tremolandi strings, a long, flowing melody rises from a solo clarinet. Eventually the first violins join in. Gradually, the movement’s first high point is reached. The sonorities Saint-Saëns drew from the orchestra here are striking and worthy of Berlioz at his most inventive: the melody is divided between flutes, English horn, and violins while a prominent place in the accompaniment is given to a solo harp. The affect is pure magic and so is the whole movement, moonlight music crafted with the sure hand of a seasoned, inventive pro – who, in this case, happened to not yet be twenty!

The finale that rounds out this most striking of first symphonies flows directly out of the slow movement: there’s no break between them, though the transition (like in Beethoven’s Fifth) feels a bit choppy. The first theme of the fourth movement recalls the opening gesture of the first, though here it’s got a bit more of a pugnacious swagger to it. In this opening section, Saint-Saëns again demonstrates his familiarity with Beethoven and Berlioz: his melodic materials are markedly triadic and his scoring (prominently showcasing wind instruments) most closely reflects the last movement of Berlioz’s spectacular Symphonie funebre et triomphale. Still, the melodic felicity could hardly come from any other hand, which becomes especially apparent as the march gives way to a series of sweeping, songful statements passed around the orchestra.

After those tunes run there course, a new section begins, this a big fugue in E-flat major. The subject itself is both triadic and scalar, not particularly interesting as a melody, but Saint-Saëns puts it through its paces with the utmost skill and a strong sense of how to build a compelling symphonic movement through contrasts of orchestral texture and melodic variety. Eventually, the march theme from the movement’s first section is interpolated into the fugue (much as Berlioz incorporated the Dies irae into the “Witches’ Round Dance” in the Symphonie fantastique, which was probably Saint-Saëns’ model for this movement), and the whole Symphony wraps up in a blaze of E-flat major splendor.

So where has this Symphony been hiding these past sixteen decades? Certainly Saint-Saëns’ posthumous reputation, which has tended to view his enormous output as uneven and too often shallow, hasn’t helped things. And there’s no denying the fact that the E-flat major Symphony is not one of the most original entries in the genre: it didn’t turn the symphony on its head, as did those of Beethoven, Brahms, and Mahler.

But the fact remains that it’s a brilliant piece, supremely crafted, wonderfully tuneful, and possessing an ending that’s rousing as they come. At the end of the day, it’s simply a fine piece of music: memorable, intelligent, and expressive. What better reasons does one need to play, hear, and otherwise get to know it?

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Excellent opening to a much needed appraisal of what I hope will be a wide-ranging coverage of more great neglected masterpieces by select composers.

Now, to bring the subject of this particular article -the Saint-Saens: Symphony No. 1 in E-b, right to the hometown – it would be interesting to know if that great interpreter of the French repertoire and the Music Director of the Boston Symphony from 1949 to 1962, Charles Munch, ever performed this — or any other of the four Saint-Saens symphonies in his concert programming Of course, we know that he often performed the Symphony No. 3 (” Organ”) and went on to make a landmark RCA – Living Stereo recording of the piece in 1959, in Symphony Hall, with the great Aeolian-Skinner organ — played by Berj Zamkochian. That recording took on a life of its own, as a sonic-state-of the art-recording, particularly with audiophiles that had sub-woofers in their stereo systems.

It was my understanding that the Boston Symphony was going to begin a project of the digital archiving of their concert programs from past seasons, much as the N.Y. Philharmonic has done with their ‘Leon Levy Digital Archives’ program. In that case, one could hopefully go through the seasonal BSO archived programs to see what specific repertoire Munch would have done during his long tenure with the orchestra. I might be missing another source here — but it would be a relatively easy way to see what other Saint-Saens symphonies, incidental pieces, etc. he might have brought in performance to those ‘golden-years’ of the Boston Symphony.

Thanks, Ron! I can promise you that the survey will be all over the map, compositionally, though I know it will (sadly) leave off plenty of deserving pieces.

You raise a very interesting question about the BSO and Munch, in particular, in this repertoire. The orchestra is evidently in the process of increasing its digital archival presence, and it’s certainly easier now to search out answers to these sort of questions than it was before. Perhaps their most useful resource thus far is an online performance database called “HENRY,” which, if you’re interested in what’s been played and when, is of great value. For many programs (at least those that I’ve searched through thus far) you can also download (or scroll through) a PDF of the original program notes, which, in addition to being quite informative, are often lots of fun to read, too.

To get to your query: according to HENRY, the only Saint-Saens symphony Munch conducted with the BSO was the “Organ” Symphony (he led it some 29 times between 1946 and 1966, both at Tanglewood and in Symphony Hall). He conducted other Saint-Saens works with the BSO – namely the Cello Concerto no. 1, the B minor Violin Concerto, the Piano Concertos nos. 2-4, the Overture to La princesse jaune, and Rouet d’Omphale – but, at least while he was here, didn’t touch any of the other symphonies. I don’t know of a similar resource for exploring Munch’s work outside of Boston, but a quick glance through his recordings at arkivmusic.com (which is about as easily searchable and comprehensive an informal database for this sort of search as I know) shows only the “Organ” Symphony in his discography.

In fact, it looks like the only times the BSO played the E-flat major Symphony was in November 1904 with Wilhelm Gericke (the full piece at Symphony Hall and the second movement the following month in Portland, ME). The first of any Saint-Saens symphony the orchestra played was the A minor Symphony no. 2 (itself a fine, underrated score): Arthur Nikisch led it at the Boston Music Hall in November 1892 and Henri Rabaud conducted it most recently at Sanders Theater in April 1919. Since 1920, the “Organ” Symphony has been the only Saint-Saens symphony in the BSO’s repertoire; the ensemble has never played either of the unnumbered ones.

Thanks Johnathan :

The Saint-Saens symphonies and other neglected French repertoire works, ( e.g,- D’ Indy : ” Symphony on a French Mountain Air ” ) would seem to be ready made for Charles Dutoit to program when he comes to guest-conduct the BSO.

l

Excellent article. I love this symphony. His 3rd seems more popular but this one is more enjoyable for me. The piano and organ cameos are nice. The finale brilliant.

Off subject, but is there a symphony written in the last 50 years that holds any water to any of these historic symphonies? I have searched and searched and everything encountered falls miserably short. I like symphonies with musical quality, not the 40+ minutes of dreary film background sounds.

Thank you so much for the insight Jonathan!

I don’t remember when I first “discovered” Saint-Saëns, but I know it’s at least more than 5 years. He’s one of my all-time favourites. I don’t know how I can relate so much with a music so far away from my homeland, yet I also enjoy Persian classical music. You can never put Persian and European music next to each other, although attempts (in my opinion, in vain) have been made.

Thank you so much for this website. This website I just discovered today when I was reading more about Saint-Saëns and his E-Flat Major symphony that I’m listening to now.