Music Remembrance: Ornette Coleman — The Gentle Iconoclast

Ornette Coleman’s music was avant-garde but, perhaps unconsciously, his notion of art as a free lyrical adventure was deeply American.

By Michael Ullman

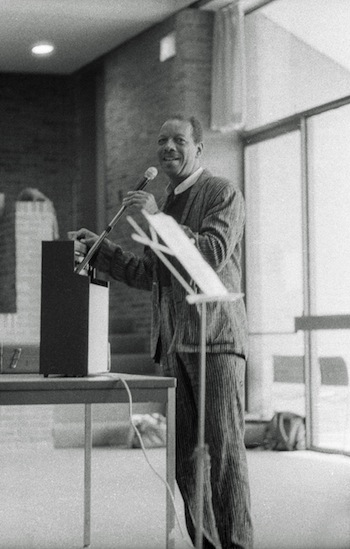

A smiling Ornette Coleman at Brandeis University in the 1970s. Photo: Michael Ullman.

Born in Fort Worth in 1930, alto saxophonist Ornette Coleman has died at the age of 85. He was an unaggressive iconoclast, a soft-spoken man, wary in public, and generous to a fault. He was an original thinker and a daringly persistent musician who, though he grew up listening to blues and to bebop on a local jukebox, at some point decided not to follow chord changes, typical or otherwise, and to play the melodies that went on in his head without regard to bar lines or chorus structures. His philosophy was simple; the results complex and — to many traditional musicians — threatening. Soprano saxophonist Steve Lacy recalled hearing some dizzying advice from Coleman: “I remember at the time (the ’50s) he said, very carefully, ‘Well, you just have a certain amount of space and you put what you want in it.’ And that was a revelation.”

The revelation wasn’t accepted immediately. He took up saxophone as a teenager and started to play in blues bands. One famous story from that time: one night he was preforming with a band down South, and Coleman decided to play what he heard in his head. He was beaten up for it, his saxophone destroyed.

After a time in New Orleans, he moved to Los Angeles where he let his hair grow and, despite the heat, walked around in an overcoat. He sounded eccentric as well, playing with his own tuning system: jazz is the one music, he insisted, in which every note can be played differently. He showed up at jam sessions, and veteran beboppers like Dexter Gordon would walk away. But he found a cadre of sympathetic musicians, including bassist Charlie Haden, trumpeter Don Cherry, and drummer Billy Higgins, who were willing to rehearse with him intensively, even when there seemed to be little chance of their performing in public. Coleman would play with those musicians for much of his life: in fact, for all his daring elsewhere, he tended to stick with core groups of instrumentalists who knew his music.

His 1959 New York debut is legendary. Everyone, we are told, and not only musicians, went to see him at the Five Spot. Jackson Pollock and Leonard Bernstein approved; trumpeters Miles Davis and Roy Eldridge did not. (Eldridge said he listened drunk and sober and could make nothing of the music either way.) Sonny Rollins was sufficiently intrigued to want to play with Don Cherry and Billy Higgins, as if he could somehow figure Coleman out by recording with his sidemen. Part of the shock must have been visual. Coleman played with a hard, uncompromising tone on a white plastic alto saxophone. Cherry performed on a pocket trumpet, perhaps left over from the Civil War. His cheeks bulging, he produced off kilter lines that were wiry and whimsical. In New York, Coleman’s group opened on a bill with what was then considered a very ‘hip’ band, the Jazztet. Here’s what pianist Paul Bley said of the juxtaposition: “The week before Ornette came [the Jazztet] sounded like a very modern, Horace Silver-type arranged band: beautiful aesthetics, with all the rough points ironed out, slick, smooth. Ornette played one set and turned them into Guy Lombardo.”

Coleman landed a contract with Atlantic Records and, beginning in 1959, he and his group produced a seminal series of recordings, kicked off by The Shape of Jazz to Come. In his notes, Coleman explained what he was doing:

My melodic approach is based on phrasing, and my phrasing is an extension of how I hear the intervals and pitch of the tunes I play. There is no end to pitch. You can play flat in tune and sharp in tune. It’s a question of vibration. My phrasing is spontaneous, not a style. A style happens when your phrasing hardens. Jazz is the only music in which the same note can be played night after night but differently each time… ‘Improvising’ is an outdated word. I try and play a musical idea that is not being influence by any previous thing I have played before. You don’t have to learn to spell to talk. The theme you play at the start of a number is the territory, and what comes after, which may have very little to do with it, is the adventure.

Ornette Coleman performing at Carnegie Hall in the 1970s. Photo: Michael Ullman.

Coleman’s music was avant-garde but, perhaps unconsciously, it was also intrinsically American. His notion of art as a free lyrical adventure echoes the ending of the quintessential American novel Huckleberry Finn, in which Huck says he will head out for “the territory ahead.” Later he doubled the size of his quartet and electrified it. He wrote for larger groups on Science Fiction, a symphony called “Skies of America,” and idiosyncratic chamber works.

Fans remember their first experience hearing Ornette Coleman’s music the way alcoholics are supposed to remember their first drink. I was in high school, and it was a few years after the initial Atlantic recordings. At the local library, I picked up a copy of This is Our Music (1960). On the cover, staring directly at me, were four disturbingly serious-looking musicians. With his straight-ahead intensity, Coltrane was at the time my idea of the avant-garde. But when I took the Coleman LP home, I heard something completely different, and unexpected: over a loosely open beat, almost a sing-song, Coleman and Cherry played a raggedy blues line while bassist Haden chugged away nonchalantly as if he was in a different world. Drummer Ed Blackwell half echoed the melody, setting up Coleman for a solo that contained braying fanfares, lyrical half phrases that might have come out of popular ballads, and sagging, sighing lines that seemed to be a nightmare version of blues, tradition transformed into a distorted fantasy. It wasn’t surprising that the tune’s title was “Blues Connotation.” Everything else about the record was just as surprising. It took some getting used to.

Coleman was unconventional, but his form of rebellion was soft spoken; the titles of his compositions reflect his gentle spirit and desire to make connections rather than generate dissent. How intimidating could a musician be whose compositions are called — without irony — “Congeniality,” “Search for Peace,” “Brings Goodness,” and “Focus on Sanity”? How considerate of him to have written the country song “Ramblin’ for Charlie Haden,’ who grew up playing and singing country music. At the beginning, some people thought Coleman was jiving, that his music was some kind of joke. He proved he had a sense of humor on pieces like “Latin Genetics,” a piece with a laughing Tex-Mex theme alternating, as do many of his more lyrical pieces, with a section of rushed downward runs that seem to come from another universe.

Ornette Coleman performing on the trumpet in Detroit in the 1970s. Photo: Michael Ullman.

Ornette Coleman came to Tufts, where I teach. He visited a class and spoke to our students. I worried about how he would be received. I shouldn’t have been. He told a story that I can only paraphrase. He said that when he first went to Japan he was surprised to be greeted by a small crowd of well-wishers as the band got off the airplane. Among them was a young man who approached him and asked, “Mr. Coleman, can I be your student?” “No,” Coleman, replied, “I do not take students.” That night outside the concert hall, he met the same young man. “Mr. Coleman, can I be your student?” “No,” he replied again, “I do not take students.” Later in his hotel room, he heard a knock on the door. It was the same young man. “Mr. Coleman, can I be your student?” He replied similarly. This went on throughout the tour. A few weeks after his return to New York, he was sitting in his Prince Street apartment, when he heard a knock on the door. “Mr Coleman, can I be your student,” asked the young man. “Come on in,” Coleman replied. It was a perfect lesson to our students, and perhaps to all of us about persistence (and perhaps politeness).

Later, I sat beside Coleman as a group of students struggled to play his music. It must have been painful to him; as he listened, he twisted a program in his hands as if to strangle it. After the session was over, I noted that he didn’t seem to have enjoyed himself. He grimaced, and said, “Why would I want to hear them play my music? I want to hear them play themselves.” Then he went up to each musician and whispered something to him, before signaling the group to start to play. It was magical. The band that had sounded awkward and ill-prepared suddenly played a free piece with power. I asked Coleman what he had told them. Different things, was the answer. He told one student to play smooth lines; another to make leaps. One he told, if I remember correctly, to play octaves. The instructions were random, but the result was a group of students listening to each other in a way that they hadn’t previously.

Later still, I interviewed Coleman for a radio broadcast. On the way to the station, he told me something that was strongly on his mind, because he also has said it to others; “You can never really be out of tune,” he insisted, “You’re always in tune with something.” He was a risk-taking giant of 20th-century jazz who, in his own mind and music, reconciled the utmost dissonance with a larger kind of harmony. He wasn’t always easy to understand, but he was always in tune with something, something else.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for The Atlantic Monthly, The New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, The Boston Phoenix, The Boston Globe and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.

.

Tagged: Billy Higgins, Charlie Haden, Don Cherry, free jazz, Ornette Coleman

I believe Don’s pocket trumpet came from Pakistan, not the Civil War. I saw instruments like it when I was living in India.

Beautiful tribute.

I learned so much from your article. Am able to appreciate his work and influence much more. I do a weekly broadcast, Thevoicemobile, at Tufts University — I didn’t know that Ornette had come there.