Music Commentary Series: Jazz and the Piano Concerto — Who Cares?

This post is part of a multi-part Arts Fuse series examining the traditions and realities of classical piano concertos influenced by jazz. The articles are bookended by Boston Symphony Orchestra concerts: the first features one of the first classical pieces directly influenced by jazz, Darius Milhaud’s Creation of the World (February 19 – 21); the second has pianist Jean-Yves Thibaudet performing one of the core works in this repertoire, Maurice Ravel’s Concerto in G (April 23 – 28). Steve Elman’s chronology of jazz-influenced piano concertos (JIPCs) can be found here. His essays on this topic are posted on his author page. Elman welcomes your comments and suggestions at steveelman@artsfuse.org.

Yehudi Wyner — the composer of the first jazz-influenced piano concerto to win the Pulitzer Prize.

By Steve Elman

A funny thing happened on my way to this survey. Bigger Issues kept cropping up, issues that are more significant than a discussion of individual musical works – many of them obscure – could possibly be. I began thinking about the essential qualities of jazz and classical music, what makes them distinctive and what might allow them to converse successfully. I considered what these JIPCs (jazz-influenced piano concertos) illuminate about those essentials. And, in view of how much rich music I discovered for the first time while compiling the survey, I wondered why so few of these pieces have any place in the repertoire today and why audiences haven’t embraced them more enthusiastically.

Every writer, if you look into his or her soul, hopes that what he or she puts in front of readers will make a difference in some way. The goals might include opening minds, touching hearts, introducing ideas, sparking actions, or starting controversies, to suggest just a few, but it would be futile to start any significant project of words without the hope of having an impact.

At the same time, every writer needs to keep some perspective. I well remember the moment, after three years of hard work, when the book I co-wrote with Alan Tolz (Burning Up the Air, Commonwealth Editions, 2006) finally appeared in the Barnes and Noble store I frequented. There it was, in an end-cap rack with a dozen other titles, in a room with hundreds of other titles, on the first floor of a store with many thousands more titles on the other floors. “My God,” I thought, “Just look at the competition!”

So I have no illusion that my survey of JIPCs and the essays that spring from it will occupy a major portion of anyone’s attention. Still, maybe over-optimistically, I hope that these posts will inspire at least a couple contemporary composers to delve into this tradition and take some inspiration from it. Maybe unrealistically, I also hope that I can contribute something valuable to the overall understanding of music. At the very least, I believe I have opened up an area of inquiry that has never received serious study before, and that may have to be enough.

Perhaps the biggest extra-musical issue prompted by my survey is this: who cares? Who cares about this tiny slice of music scholarship? Indeed, who cares about the whole framework of creative endeavor? The simple answer is: not very many.

The more I listened to these works, the more an old unease nagged at me: perhaps the many acts of serious music-making – composing, performing, producing, analyzing – are so far removed from the daily lives of average people that they may have no practical value at all in the modern world. To simplify ridiculously, what possible difference can it make to a mother with Ebola or a diplomat trying to resolve an international conflict or a family displaced by fanatic warriors that a composer of music chooses to integrate jazz elements into a piano concerto? Would that concerto make any difference to any of these people, even if they were told that the composer had won the Pulitzer Prize for such a piece of music (as, in fact, Yehudi Wyner has done)?

In a word, the answer to that last question is: No.

Creativity is not limited to high art, and the majority of people appreciate creativity more when it enhances something practical. “Art” used to mean something like “craft,” and modern usage – as in “the art of the deal” – has brought the word back to an old and venerable meaning. For lovers of the physical incentives provided by electronic dance music, the immediate impact created by dramatic evening wear, the elegance and comfort of craft furniture, and the balance and proportions of hand-made firearms, just to name four, practical usefulness and art co-exist comfortably. It is only when things become too esthetically valuable to be utilized practically that they rise into the peculiar circle of high art, and even then a sliding scale is constantly applied. Even the core works of classical music have substantial practical value in this modern world; a large number of people come to Bach, Mozart, Schubert, and Chopin for the calm and order their music provides, for a peaceful island in the sea of their daily troubles.

But most JIPCs are not particularly practical, even in this sense. Like many works of pure art, they have no purpose other than their own ingenuity and beauty. Some of them are too exciting to be background music. Some of them use jazz for its shock value. Within the vast range of art works, they have a very small place. It is not even a matter of whether or not a listener will enjoy any of these works; it is a matter of whether a listener will even be aware that compositions of this kind exist.

The human preference for short-term gratification is nothing new, but the media tools now available have brought us closer than ever to getting the amusements we want as soon as we want them, and this reality puts all forms of art music at a serious disadvantage.

The appreciation and enjoyment of art music requires a certain amount of work – satisfying work that involves attention and care and consideration, but work nonetheless. Most people prefer not to work, especially intellectually. Strike one. Given the wide availability of so much that is so easily consumed, the opportunities art music has to reach the soul of a receptive listener in the modern world are very limited. Strike two. Music requires absorption in real time; there is no way to shortcut listening. Strike three.

The potential fourth strike for art music in general, and especially for JIPCs, is the abstractness at the core of musical experience. The average listener typically wants a lyric or a program or a context to tell him or her what music “means,” but the full experience of hearing any piece of music defies a simple reduction. If it were possible to convey those feelings and messages in other media, there would be no need for the music in the first place.

For the tastemakers and those who categorize, music inevitably falls under the umbrella of amusement (“Arena” and “Off Duty” in The Wall Street Journal; “Entertainment” in The Washington Post; the old “g” tabloid section of The Boston Globe). That old fogy, The New York Times, still sees fit to use “The Arts” for the pages where music reviews and discussions reside. And Arts Fuse? – goodness, how quaint.

(And bravo to the Globe for bucking the general trend with its 2015 rethinking of its daily “Living/Arts” sections. “g” is gone now, and the dangerous and off-putting word “Arts” has been restored to reviews, comments, and columns that appear in those specialty sections almost every day.)

Under all of the nebulous euphemisms for “art,” narrative and visual media take up the lion’s share of column inches and site pages, probably because it is so much easier to deal with the visual and concrete – painting and sculpture can be represented by photographs; ballet, movies and theatrical presentations can be illustrated with stills and production shots. Even when the thirty-second clips of music that are permitted under “fair use” rules appear in audio media or on-line reviews and discussions, they cannot effectively capture the scope of complete musical performances.

As one more strike, consider that jazz-influenced piano concertos are a subset of a subset (concertos) of a subset (classical music) of a subset (art) of a subset (amusements), of the general category of human activities, with each subset representing perhaps 10% or less of the set preceding it. Conclusion: the chance that any of these works has of reaching an ideal listener seems very slim indeed.

These dark thoughts led me back to the work of Ellen Dissanayake, a multi-disciplinary thinker who has been a frequent inspiration to me for decades. It would be unfair for me to try to summarize the many insights of her three books, especially Homo Aestheticus (Free Press, 1992), but one of her core messages is significant here. She proposes that art has been evolutionarily important in human history and that all of us have deep psychosocial impulses towards it:

Art, as the universal human predilection to make important things special, deserves support and cultivation . . . . Art is a normal and necessary behavior of human beings that like other common and universal human occupations and preoccupations such as talking, working, exercising, playing, socializing, learning, loving, and caring should be recognized, encouraged, and developed in everyone.

Still, she is troubled by some parts of the contemporary landscape:

It seems worth asking whether the confusing and unsatisfying state of art in our world has anything to do with the fact that we [that is, the great majority of people in the developed nations] no longer care about important things. In our predominantly affluent and hedonistic society survival is no longer paramount for most of us . . . Caring deeply about vital things is out of fashion, and in any case, who has the time (or allows the time) to care and to mark one’s caring?

And these observations come from the early 1990s, before anyone had a smartphone.

Ellen Dissanayake, author of “Homo Aestheticus.” She proposes that art has played an important role in human evolution.

It is characteristic of the past 100 years that spectacle, which has always been an irresistible bauble for human beings, has gradually pervaded every area of art, attracting many who would otherwise have no interest in museums, concert halls, or theaters. The lives of most people in the First World are already stuffed full of stimuli; most people have no urgent spiritual need for internal exploration, for art works that will stretch their perception or challenge their understanding or even demand their full attention.

And a vastly greater number throughout the world don’t even have the luck to consider these spiritual issues. Poverty makes survival paramount; it is only when we have some confidence in our survival that we can begin to think about putting images on the walls of our caves or dancing at our tribal festivals.

But Dissanayake says the impulse towards the creative is always there, fostered within us evolutionarily, and we will seek to satisfy it if we are at all able to do so. A poignant case in point: the photos in January of self-exiled Syrians making snowmen in a Jordanian refugee camp.

For those of us lucky enough to have the resources and the time, deep exploration of this internal landscape, where we can reach out to the unknowable, discover the inexpressible, and enrich ourselves beyond the material, is a satisfaction beyond any other. Any creative endeavor must begin with the optimistic hope that it will somehow find some place in that great landscape.

One can assume that there will always be people who DO care. In every generation, there have been and probably will be a handful of people who seek something deeper, something nameless, something beyond the now. For them, the creative endeavor is palpable. “Literature” has a physical reality beyond any shelf of books. “Drama” is a grand edifice above the proscenium of any theater. “Music” is a visceral substance that persists when mere sounds die away.

Perhaps these special people have always been and will always be a tiny minority. When I watched the broadcast of the Los Angeles Philharmonic’s opening night with Gustavo Dudamel a few years back, I was stunned by John Adams’s “City Noir” (released subsequently on video, and in 2014 in an outstanding CD by the St. Louis Symphony paired with his saxophone concerto). Its conclusion literally pulled me out of my seat, and I expected the LA audience to react in the same way. However, during the applause that followed the piece, the camera panned over the audience, and instead of boisterous enthusiasm, I saw a polite appreciation on most faces, with puzzlement on more than a few. So I cannot trust my own perceptions; when I listen to JIPCs and marvel at their inventiveness and color, I may not be able to understand how difficult some may find the music.

On one hand, in every major market in the US, there are enough people who care to allow a symphony orchestra to function – not always well, and not always profitably, but at least to survive. Venues for jazz persist in nearly every city because there are just enough people to make them commercially viable. On the other hand, all-classical radio stations survive in less than half of the nation’s major markets, and all-jazz stations, never by any means common, are now very few and very far between. Who can say how long the institutions of and venues for live art music will continue, and what will take their places in the lives of the people who care?

We are surrounded now by technological and societal cobwebbing. Focusing on these nearby phenomena makes them seem much more important than they really are. If we refocus our eyes for the long view, the cobwebbing disappears.

We have to seek the basics of caring, the things that matter. A lifetime of listening has given me the sense that there are three elements that contribute to the immediate appeal of a piece of music: singable melody, danceable rhythm, and what might be called spiritual uplift – a listener’s sense of personal enrichment somehow triggered by those organized sounds. From the simplest folk forms to the most complex modern works, the ones that quickly catch the ear contain major doses of at least one of those three elements, and the ones that rise to the top of the charts or to the pinnacle of art are the ones that use those elements most powerfully. And in many cases, any one of these three basics can open the doors to much more.

Spiritual uplift is the most personally defined of the three basics, and in some sense, it defines the appeal of art music for each person – the more deeply someone is willing to go into his or her own soul, the more likely it is that that individual will find spiritual uplift in more serious music. Spiritual uplift is not necessarily transcendent or profound. It ranges from persistent ephemera like “Celebrate” by Kool and the Gang to sophisticated crowd-pleasers like Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture to works of grand ambition like George Russell’s “The African Game,” but the feelings they evoke are related. And “uplift” is relative. The spirit can be as enriched by melancholy as by joy, and a corresponding thread binds Paul McCartney’s “Yesterday,” Miles Davis’s interpretation of “My Funny Valentine,” and the adagio from Samuel Barber’s String Quartet. In fact, it is spiritual uplift that provides some solace in a time of discomfort. Whether we live in a hovel or a palace, music can soothe, even heal.

But before any of this magic can occur, somehow the listener has to be brought to the music.

Let’s bring this back to earth, and to the topic at hand. Who cares about JIPCs?

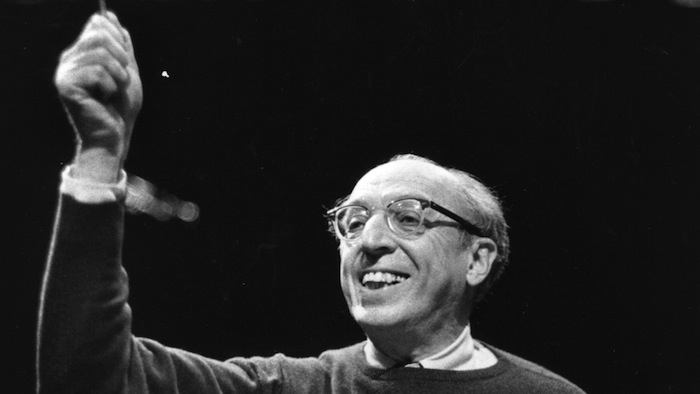

Aaron Copland — his Piano Concerto has an appealing use of rhythm as well as an interest in more serious spiritual uplift.

The two most popular are Maurice Ravel’s Concerto in G and George Gershwin’s Concerto in F. As I mentioned, the Ravel is part of the 2014-15 Boston Symphony season, but it also appears in the programs of six other major American orchestras, in New York, Chicago, Houston, Atlanta, Pittsburgh, and San Francisco. Only one piano concerto by any other composer has more performances in major US cities during this season – Rachmaninoff’s third – and only one – Beethoven’s first – will be performed as often.

Gershwin’s Concerto in F is nowhere near as popular, at least this year. Perversely, only two significant American orchestras – the Buffalo Philharmonic, led by JoAnne Falletta, and the Indianapolis Symphony, led by Jeffrey Kahane – have programmed it in their regular seasons. There are two other performances, in New York and Seattle, by the London Symphony during its March – April US tour. However, if you consider all the other orchestral works by Gershwin that are programmed in the 2014-2015 season – including “Rhapsody in Blue,” “An American in Paris,” “Cuban Overture,” “Catfish Row,” and orchestral arrangements of his songs – his music will be heard 15 times in 11 cities, not including Boston, by the way. Only three other composers are being so broadly programmed in this season – Mozart, Rachmaninoff and Beethoven. (The reasons that Gershwin’s piano concerto is comparatively so unpopular with American orchestras will have to wait for a later post.)

These two pieces satisfy my three basic criteria of appeal – and how. Each has singable melody to spare. Each has sections of powerful rhythm that dance, at least in the head. And each makes the listener feel enriched and fulfilled. Perhaps Ravel aims higher in the spiritual uplift department than Gershwin does, but Gershwin’s incredible gift for melodies that are touching as well as singable makes his work a very close second.

Does this mean that these two pieces are the most immediately appealing in the history of the JIPC? By no means. I would put six other concertos at the top of the appeal heap, and only one of them gets heard with any frequency.

Here are three pieces that are nearly as melodic as Gershwin’s and Ravel’s: Jean Wiéner’s “Franco-Américain” Concerto, Arthur Benjamin’s Concertino, and Avner Dorman’s Concerto in A.

Three more may not be so melodic, but they deserve a lot more attention than they receive. Aaron Copland’s Concerto is more challenging harmonically than the five others above, but it has enormous humor and verve; it has just enough of a reputation to give it an occasional concert hall outing. John Adams’s “Century Rolls” has some minimalist repetition and some challenging harmony, but its relentless power and colorful orchestration should generate more performances than it has had so far. William Schuman’s Concerto builds on Copland and Gershwin with great ingenuity, high-spirited drive, and considerably more advanced harmony, but Schuman’s reputation as a “difficult” composer has effectively frozen his work out of symphony programs.

As for the appealing use of rhythm, Copland, Benjamin, Schuman and Adams all get high marks, although the forward thrust in these pieces isn’t as consistent as it is in the Gershwin Concerto. Of these six composers, Copland, Schuman and Adams aim for more serious spiritual uplift, and because of that ambition, I find their works more satisfying than those of the other three.

Would listeners care as much for these pieces as they do for the Gershwin and Ravel? They would care, I think, if they could hear them with some regularity. Would they care for other JIPCs if they had sufficient grounding in the more immediately-appealing works? I think they would.

To help you explore other compositions mentioned in the piece above as easily as possible, my full chronology of JIPCs contains detailed information on recordings of these works, including CDs, Spotify access and YouTube links.

Next in the Jazz and Piano Concerto Series — Big Issues: Who will buy? Who will program?

Steve Elman’s four decades (and counting) in New England public radio have included ten years as a jazz host in the 1970s, five years as a classical host in the 1980s, a short stint as senior producer of an arts magazine, thirteen years as assistant general manager of WBUR, and currently, on-call status as fill-in classical host on 99.5 WCRB since 2011. He was jazz and popular music editor of The Schwann Record and Tape Guides from 1973 to 1978 and wrote free-lance music and travel pieces for The Boston Globe and The Boston Phoenix from 1988 through 1991.

He is the co-author of Burning Up the Air (Commonwealth Editions, 2008), which chronicles the first fifty years of talk radio through the life of talk-show pioneer Jerry Williams. He is a former member of the board of directors of the Massachusetts Broadcasters Hall of Fame.

I just listened to John Adams’s “City Noir” because the way you mentioned it made it sound interesting.

Thank you!