Visual Arts Feature: Visiting The Barnes Foundation, Part One

Spending the better part of two days inside the Barnes Foundation was a transformative experience that changed the way I look at art.

The Barnes Foundation at night. Photo: The Barnes Foundation Archives and Special Collections, Merion, Pennsylvania.

[The second part of this article on visiting the Barnes Foundation can be found here.]

By Helen Epstein

I’m married to a Parisian ambivalent about his birthplace, so when it came to celebrating our 30th anniversary we flew not to the French capital of love, but to the closer, far less ballyhooed Philadelphia. If you haven’t been there for a while or ever, this American cultural capital will surprise you, especially now that the Barnes Foundation has moved from suburban Merion to join the Rodin Museum and the Philadelphia Art Museum along the Benjamin Franklin Parkway. The area is dotted with hotels, restaurants, and cafes, and is an easy winter week-end getaway for New Englanders. Our primary destination was The Barnes Foundation.

The Barnes opened in the center of Philadelphia in May of 2012, 60 years after the Philadelphia Inquirer initiated a lawsuit to open the collection to the public. The decades-long fight over the collection was explored by the 2009 documentary The Art of the Steal, framing it as a legal travesty and theft by a coalition of Foundation trustees, politicians, and corporate philanthropists.

This coalition of elites built a stunning new building on the site of a former juvenile penitentiary on Philadelphia’s Museum Mile and opened it to much controversy from near and far. For a disgruntled take on the issues, here is Jed Perl in the New Republic.

I’m with the philistines who welcomed the move. A few of my friends had, over the years, managed to get into the fabled collection in Merion via art school or personal contacts, but the location (five miles outside Philadelphia proper) and arcane rules of admission (phone reservations two weeks ahead of time; highly restricted days and hours of public access) had dissuaded me from even trying. Now that the Barnes was (almost) as user-friendly as any major American museum, we were psyched to finally visit.

![Helen Epstein and Penny [] with portrait of Barnes by Photo: Patrick Meyer](https://artsfuse.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/helen-and-penny-with-protrait-of-barnes.jpg)

Helen Epstein and docent Penny Hansen with a portrait of Albert C. Barnes by de Chirico. Photo: courtesy of Helen Epstein.

Barnes was a product of Philadelphia’s public schools, including the academic Central High School, from which he continued on, like many graduates, to the University of Pennsylvania. He paid for his tuition by tutoring, boxing, and gambling. He graduated with a medical degree, studied briefly in Germany, but, rather than becoming a physician, he chose to enter industry.

In 1899, when he was 27 and before antibiotics were invented, Dr. Barnes entered into a partnership with Dr. Herman Hille, a chemist who developed Argyrol, an anti-septic drug that was used for gonorrhea-caused infant blindness as well as sore throat. The partners had their differences. Dr. Barnes’ tetchy, bellicose personality generated a considerable amount of conflict in his life and, in 1908, he bought Hille out. He established the A.C. Barnes Company in Philadelphia, hiring five white women and three black men to work there. He married Brooklyn-born Laura Leggett, and had a home built on the Main Line.

As his business prospered and Barnes had more leisure time, he found himself at odds with his high society neighbors but like some of them became interested in collecting art. In high school he had dabbled in painting alongside his classmate William Glackens, who had become a member of New York’s artist group “The Eight.” In 1911, he reconnected with Glackens and, a year later, asked him to scout Paris for paintings. The first major exhibit of Glackens’ work in 50 years is now at the Barnes through February 2.

Through Glackens, Dr. Barnes gained access to art dealers and collectors, including Amrican ex-pat Leo Stein. The now millionaire manufacturer began buying up Renoirs, Matisses, Cezannes, Modiglianis, Van Goghs, Daumiers, Manets, Rousseaus, Lautrecs, Bonnards, de Chiricos, Soutines as well as European art from earlier periods, including by Frans Hals, Durer, El Greco, and Bosch.

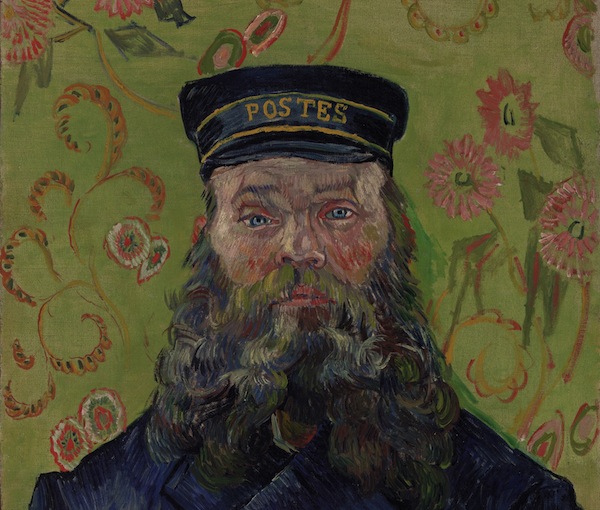

A partial view of Van Gogh’s “Postman,” acquired by Glackens in 1912.

He hung the paintings in his factory as well as in his home. He saw himself as an enlightened employer and an arts educator. “Studying good paintings,” he wrote in his first article on the subject, “offers greater interest, variety, and satisfaction than any other pleasure or work a man could select…” He implemented his philosophy by mandating that for two of the eight hours his employees worked they would receive Adult Ed: reading selections from William James, Bertrand Russell, George Santayana, John Dewey, and Roger Fry.

In 1917, Barnes took a philosophy course with Dewey at Columbia University and became a devotee of “experiential education” and “learning by doing.” That led him to expand his factory seminars into a full-blown educational institution with an emphasis on the fine arts.

In 1922, he obtained a state charter to establish an educational Foundation, dedicated to promoting fine art and horticulture. He purchased a 12-acre arboretum in Merion (where Mrs. Barnes later established a horticultural school) and hired a French architect to design a home for his acquisitions. Friends persuaded him to show part of his collection at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, but, when it opened in the spring of 1923, the exhibit and Barnes himself were roundly panned by Philadelphia’s art establishment. “It is hard to see why the Academy should sponsor this sort of trash,” wrote one local critic.

That experience, his exclusion from Philadelphia’s high society, his hostility to the city’s institutional establishment, and his radical ideas about worker education, cemented Barnes’ resolve to create an alternative art collection. In 1925, when he opened what he called his “great house of art,” Barnes made admission difficult for both members of the academy and Philadelphia high society. The Barnes Foundation was not a museum, he stressed, but an educational institution. Its mission was to invite working people, disenfranchised people and young artists — black and white — to learn Barnes’s principles of visual literacy and to take a three-year course, earning a certificate in Art Appreciation if they wished. Although Dewey and renowned conductor Leopold Stokowski spoke at the ceremony, the press didn’t cover it.

Barnes went his own way, adding to his collection, reassembling it, creating a Journal of the Barnes Foundation, in which he published articles such as “The Art in Painting,” where argues that “to see as the artist sees is an accomplishment to which there is no short cut, which cannot be acquired by any magic formula or trick.” He taught his own way of seeing — viewing art through the four lenses of light, line, color, and space — and elaborated on them in a series of articles and books. He developed close ties with nearby Lincoln University, which bills itself as “the first institution found anywhere in the world to provide a higher education in the arts and sciences for male youth of African descent.”

Albert C Barnes (l) William James Glackens circa 1920. Barnes assigned his friend to roundup “modern” art for him in Paris. Photo: Unidentified photographer/ The Barnes Foundation Archives and Special Collections, Merion, Pennsylvania.

A few months before the stock market crashed in 1929, Barnes decided to sell his company and, as a consequence, was able to buy up hundreds of important paintings from suddenly destitute but art-rich collectors. By the time he was killed in a 1951 car accident at the age of 79, Barnes had amassed 9,000 pieces including 181 Renoirs, 69 Cezannes, 60 Matisses, 44 Picassos, and 14 Modiglianis. About one quarter of his paintings are by Americans: Glackens, Cassatt, the Prendergast brothers, Hartley, Avery, Demuth and local African-American painter Horace Pippin. The rest includes African masks, hand-crafted metalwork, ceramic plates and vases, and Pennsylvania Dutch furniture.

That enormous and heterogeneous collection was, during Barnes’s lifetime, constrained by an elaborate system of rules. No piece could leave the premises for any reason. No loans, no traveling exhibits. No posters, postcards or any other kind of photographic reproduction. Access was restricted to people Barnes approved. Artist Ben Shahn, for example, was allowed in, then banned. The Collection, visitors were reminded, was not a museum, but an educational foundation with its own arcane practices and hours.

Today, the Barnes has become the epitome of a state-of-the-art establishment museum. Designed by architects Tod Williams and Billie Tsien, it features the requisite landscaping (complete with reflecting pool), Free First Sundays, Young Professionals’ Nights, Light Court for private functions and corporate parties, audioguides that include a wide range of experts (including from Barnes’ nemeses Penn and the Philadelphia Museum of Art), a restaurant, café and a gift shop and even two free Barnes apps: here and here.

The collection is now estimated to be worth more than that of your average museum: upwards of $25 billion.

Given all the build-up, I was worried that the Barnes Foundation might have been a big disappointment. But I was wrong. Flying to Philadelphia and spending the better part of two days inside the Barnes was a transformative experience that changed the way I look at art.

Helen Epstein is a cultural journalist and author whose work, including a profile of art historian Meyer Schapiro, can be found at Plunkett Lake Press.

Loved this. Excellent. So enjoyable.

By the way, I am one of those anointed who saw the collection in situ and harbor a Luddite’s perspective on accessibility. I loved the crotchety admissions policy. Art is to be revered and not commodified in my humble

opinion.

Hallie Cohen

Associate Professor

Chair, Art & Art History Department

Director, Hewitt Gallery of Art

Division of Fine and Performing Arts

Marymount Manhattan College

221 East 71st Street

New York, N.Y. 10021

hcohen@mmm.edu

phone: 212-517-0691

fax: 212-774-0770

http://www.halliecohenart.com

http://www.philoctetes.org

Wonderful write-up. I enjoyed learning more about the Barnes Foundation by viewing The Art of the Steal earlier this year, and of course, first hand from my dear old dad, Herb Mandel, who lives to talk about his days as a student there. Here’s a link to one of his recollections.