Theater Review: Of Sex, Death, and Ducks

Let us hob-and-nob with Death — Alfred, Lord Tennyson

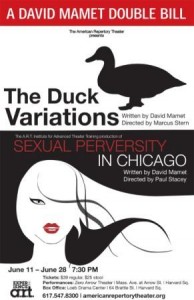

The Duck Variations by David Mamet. Directed by Marcus Stern. Sexual Perversity in Chicago by David Mamet. Directed by Paul Stacey. Presented by the American Repertory Theatre at Zero Arrow Street, Cambridge, MA, through June 28.

The Duck Variations by David Mamet. Directed by Marcus Stern. Sexual Perversity in Chicago by David Mamet. Directed by Paul Stacey. Presented by the American Repertory Theatre at Zero Arrow Street, Cambridge, MA, through June 28.

Reviewed by Bill Marx

Death be not mentioned in David Mamet’s early short play, “The Duck Variations,” which was first produced in 1972. Of course, it is the playwright’s deft handling of linguistic indirection that makes the script, which deals with two old men trying to ignore oblivion, so genially comic.

Ironically, the aged treading warily around The End holds up better than Mamet’s once-shocking look at twenty-something erotic mores in “Sexual Perversity in Chicago,” first produced in 1974. The decades have not been kind to this play and its critique of fowl-mouthed macho puerility. What with the arrival of AIDS, texting, cell phones, and ‘hooking up,’ the piece creaks much more loudly than the squabbling geezers in “The Duck Variations,” who are brought to compelling life in fine performances by Thomas Derrah and Will LeBow.

The set-up of “The Duck Variations” is simple enough – two old men, Emil Varec and George S. Aronovitz, sit on a park bench “on the edge of a Big City on a Lake” on an Easter afternoon.They appear to talk about whatever comes into their heads, but a sense of fear, rooted in intimations of irrelevance, exerts an invisible pressure on the seemingly banal conversation, organized around fourteen ‘variations.’

The talk is often triggered by what Emil (Derrah) and George (LeBow) see around them: a glimpse of a boat inspires speculation about who is on board; the sight of a duck inspires an ongoing discussion about the bird’s life cycle, its relationship to predators, such as the Blue Heron, and the differences, if any, between ducks and pigeons. Their wrangling over the lifestyles of fowls, including the allegedly super-secret mating habits of “barnyard” ducks, generates plenty of wry amusement.

But the trivial observations, the pseudo-scientific generalizations about nature inevitably lead the pair to talk about extinction, which is just where they don’t want to go. “You upset me … with your talk of nature and the duck and death,” says Emil mid-way through the play. The joke is that these guys, who never leave the bench, are doing their best to ignore the fact that they are ‘sitting ducks.”

Mamet explores this dark irony with sympathy and humor, such as when Emil, unconvincingly but gallantly, tries to reassure George that there is a meaning to their exchange on the park bench: “There’s nothing that you could possibly name that doesn’t have a purpose. Don’t bother to even try … The very fact that you are sitting here on this bench has got a purpose.” While rooted in a touching need for solace, the shaky claim to significance is continually undercut by what the men say about themselves, as when Emil describes how he escapes his apartment (“Joyless. Cold concrete.” ) by going to the park.

According to the Mamet, the idea for the play came “from listening to a lot of old Jewish men in my life, particularly my grandfather.” Thus, even though “The Duck Variations” owes something to Edward Albee and Samuel Beckett’s exploration of talk as a hapless deferment from reality, the playwright’s deft use of Hebraic spin, his manipulation of homey rhythms and prosaic cadences, takes the notion in a fresh direction. LeBow and Derrah manipulate the dialogue with agility, especially showing how the confab wavers between an unspoken friendship and undercurrents of hostility – exasperation is a small price to pay when the enemy is lethal boredom.

The wonderful ending, in which George evokes the value of the aged among the ancients Greeks is a poignant meditation on the play’s tragicomic vision: “Old Men. Incapable of working. Of no use to their society. Just used to watch the birds all day. First Light to Last Light. First Light: Go watch birds. Last Light: Stop watching birds.” There’s little of Beckett’s cosmic terror in this evocation of geriatric uselessness, but it’s affectionately frightening nonetheless.

Mamet appears to care about Emil and George in “The Duck Variations,” which lends its satire of the gabble of isolated oldsters a gentle humanity, a saving sense of empathy. “Sexual Perversity in Chicago” offers some nostalgic chuckles, but it has lost a lot of its sardonic sting as an indictment of the savage mating rituals in the American urban jungle.

The influence of the aggressively misogynistic and sexual predatory blather of Bernie on his friend and co-worker Dan waxes and wanes through the course of the play, which is made up of a series of brief, explosive scenes. Dan meets Deborah: their coupling blooms and curdles under the jaundiced eye of Deb’s cynical roommate Joan and the cartoonish cad Bernie who, in one scene, reacts to a woman’s rejection at a bar with adolescent anger: “You think I don’t have better things to do? I don’t have better ways to spend my hours than to listen to some nowhere cunt try out cute bits on me? I mean why don’t you just clean your fucking act up, Missy.” The play’s caricatures have been molded to show us that in narcissistic America relationships between the sexes are driven by anxiety, insecurity, mythology, and distrust. The figures are too one-note to do more than trumpet that message.

To work, a production of “Sexual Perversity in Chicago” has to race along with ferocity and finesse. Under the lackluster direction of Paul Stacey, the play plods a bit, even with a game cast made up of first-year acting students at the A.R.T./MXAT Institute. The performers are capable enough, but they don’t deliver Mamet’s dialogue with the requisite snap and crackle. A few of the scenes fall flat or come off as forced. Bernie’s long-winded, fantasy-filled sexual conquests still generate laughs, but the play feels dated, light years from a sexual scene among the young that, at least from what I see and hear, is less obsessive and more relaxed, more about communal ‘peeling off’ and ‘hooking up’ than prowling for pick-ups. Speaking of pick-ups, Zero Arrow Theater has been comfortably converted into a cabaret for the evening of Mamet plays, including a bar, which was skillfully used for a couple of scenes.

These shows were part of a two month A.R.T. “celebration” of the work of Mamet, but what is called for now is thoughtful reevaluation, including critical speculation about whether the dramatist’s dedication to making films and TV shows has been healthy for his playwriting. His recent crude turn to the Right (“Why I Am no Longer a ‘Brain-Dead Liberal'”) could be part of the discussion as well. “The Duck Variations” displays a strong talent (if he wrote the play today, however, the geezers might salute “the unregulated free market”), but “Sexual Perversity in Chicago” suggests that some of Mamet’s highly praised plays — once their shock value has worn off — are beginning to show their age. Has Mamet written a play since 1984’s “Glengarry, Glen Ross” that would be considered major?

Tagged: American-Repertory-Theatre, David Mamet, Sexual Perversity in Chicago