Fuse Film Feature: Confessions of a Movie Critic — Waiting for His Next Close-up

Who doesn’t want to be in a movie?

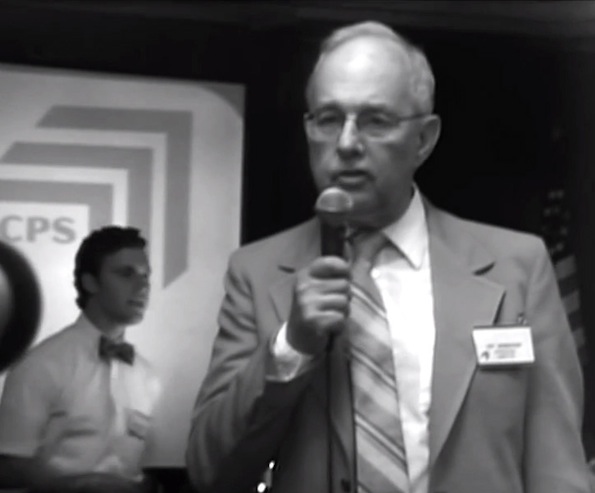

Stardom calls? Fuse Critic Gerald Peary plays chess champ Pat Henderson in the film “Computer Chess.”

By Gerald Peary

The last time I acted was more than forty years ago, sporting a tuxedo and a dubious British accent in a rickety college stage production of Noel Coward. Today, I’m a Suffolk University professor and a local film critic. So how, out of nowhere, did I land a rather plum role in Andrew Bujalski’s Computer Chess (January 30 at Suffolk University’s Modern Theatre, February 2 at the Brattle Theatre), one of the better-received independent film features of 2013? I’m cast, comically, as a brash, conceited chess champion.

“It’s obvious how you were picked,” person after person has told me. “You must have known the director.”

Well, I do know Bujalski. But I’ve known many directors, having interviewed filmmakers for four decades. But nobody in all that time has looked across the table during a Q&A, checked out my profile and said, “You ought to be in pictures.” Nobody has offered, “I’m going to make you a star.”

But why me in Computer Chess? Bujalski’s casting philosophy is to utilize friends, ex-college roommates, and sundry non-professionals. I qualify. And it couldn’t hurt that I’ve been a long-time supporter. He directed his precocious first film, Funny Ha Ha (2002), while still an undergrad at Harvard. I was the first to program it, a special screening at the Coolidge Corner. With Mutual Appreciation (2005) and Beeswax (2009). Bujalksi gained a reputation as perhaps the most talented filmmaker of the so-called ”mumble core” film movement. As a critic fan, I helped define that movement: a chronicling of the everyday lives of well-educated post-college grads who falter at work and love and speak in an inarticulate, circuitous manner, peppering conversations with “like,” amazing,” and “awesome.”

I’ve savored Bujalski’s twenty-something cinema, though mostly in an anthropological way. I’m from such a different generation. So what a surprise when I got an e-mail in 2011 from Austin, Texas, where Bujalksi, now in his 30s, has gone to live. The e-mail: Would you like to audition for my new film?

Would I be Pope for a day? Who doesn’t want to be in a movie? Bujalki sent me a paragraph description of a scene in which chess champ Pat Henderson has an argument with a New Age guru about who has rights to be in a hotel room. Do the scene three times, Bujalksi requested, record it on video. Fortunate for me, my department administrator at Suffolk, Mike DiLoreto, moonlights as a local theatre actor. Anchored by his expertise acting the guru, we improvised the scene three ways. I shipped off the tape. And then, depression. I was lousy, I decided, a rank, raw, unfunny amateur. My movie career was over before it had started.

The days passed.

Finally, another e-mail from Bujalksi. We are flying you down to Austin for the shoot. Elation! And several weeks later, I arrived in Texas, ready to go.

Computer Chess, unlike Bujalski’s other three films, is a period piece, set in the early 1980s. And many of the characters are adults. It’s the dawn of the digital age, a world of bulky, clunky video hardware, and a time when human chess players still were capable of beating computers. My character, Henderson, sets up a weekend competition of computer chess teams. On the final day, Henderson confidently takes on the computer winner, certain of victory. That’s what I knew about the movie, a narrow part of the plot.

Bujalski’s method on Computer Chess was to keep the total story a secret from the actors. If there was a screenplay, I never saw it. Each day’s scenes were sort of improvised. “You might say something like this,” Bujalski would float ideas. I’d nod, sit down and write my dialogue, then show it to my director. Almost always, he would approve what I wanted to say. Bujalksi was only strict when it came to chess terminology, and that we would check for accuracy with a real chess champion who was daily on the set. I was hardly the expert: I had retired forever after winning my high school championship. My last chess game was 5l years earlier.

“It must have been hard to improvise,” people have commented. Actually, not hard at all. It was easier than memorizing a script. I felt comfortable acting in Computer Chess for a simple reason. Bujalksi, unlike many filmmakers, is a genuinely nice, supportive guy. I don’t know what I would have done if the director was a martinet, bullying his fragile actors. Cry? Anyway, we shot for eleven days, I returned to Boston. And waited. And, in January 2013, success: Computer Chess premiered at Sundance.

I have the shakiest memory of watching myself there on the big Sundance screen, this apparition saying lines. Who was that person? I felt so disconnected. Was I good? Was I bad? I think I was astonished that so much of what I shot remained in the movie. I actually have a substantial role! And then I became anxious: Bujalski had taken a major chance putting me, an acting nobody, in the spotlight. If I was terrible, Computer Chess would be a failure.

Happily, audiences liked Computer Chess, and critics even more. To my astonishment, I got good reviews for my acting. And when it came time in December for Best of 2013 lists, I was listed by several kind critics among their picks for Best Supporting Actor. In fact, I finished 37th among polled Indie Wire critics, ahead of George Clooney for Gravity.

“Would I want to act again?.” friends ask. Why, of course. But so far, there have been no offers. I think my Computer Chess performance is considered as a one-trick pony. Cute, but that’s all he can do. Yet cocky as chess champ, Pat Henderson, I know better! Casting agents, take note: I’m waiting for my next close-up.

Gerald Peary is a professor at Suffolk University, Boston, curator of the Boston University Cinematheque, and the general editor of the “Conversations with Filmmakers” series from the University Press of Mississippi. A critic for the late Boston Phoenix, he is the author of 9 books on cinema, writer-director of the documentary For the Love of Movies: the Story of American Film Criticism, and a featured actor in the 2013 independent narrative Computer Chess.