Visual Arts Review: “Maus” and More — Art Spiegelman at the Jewish Museum

Art Spiegelman believes that “MAD” magazine was more subversive for his generation of protesters than either marijuana or LSD. It certainly radicalized him.

Art Spiegelman’s Co-Mix: A Retrospective at the Jewish Museum in New York, through March 23, 2014.

By David D’Arcy

A retrospective devoted to Art Spiegelman seems like gilding the lily. In an art museum, even more so – like saying “art” twice.

Spiegelman’s Holocaust masterpiece, Maus, first published as book in 1986, and completed in 1991, is a complex biography of father and son – anguished, humane and comic — a retrospective in itself. His meditations on Maus published since then are broader reflections on himself, his family, his art (and that of many other artists) and on the direction of the world.

Did I leave anything out? Spiegelman – a historian of his comics medium and himself — rarely does. Not that he always expects to be understood. Even after the public discovered Maus, the memoir was originally classified by the New York Times, on its bestseller list, as fiction.

The Times corrected that error, but despite Spiegelman’s reputation today, comics are barely represented in museums (with France being an exception) – and certainly less than video games, which come from an industry with far more cash behind it.

CO-MIX – ART SPIEGELMAN: A Retrospective of Comics, Graphics and Scraps, the tribute now at the Jewish Museum in New York, is the fifth stop on a tour that began in Angouleme, France, at the Musee de la Bande Dessinee (Comics Museum), and traveled to Paris (Centre Pompidou), Cologne and Vancouver. There’s a New York connection to almost everything on view. Most of it was drawn here.

The survey of Spiegelman’s work doesn’t start with Maus, even though, for those of us outside the comics world, our awareness of Spiegelman does.

Spiegelman is the product of paradoxically tragic and miraculous circumstances – – two parents deported to Auschwitz who each survived the camps — yet his work was nourished (if that’s the word) in comics, a medium that was scorned and devalued – but also affordable. He started out as a “slob snob,” formed by MAD magazine. The publication’s mantra – “don’t believe anything you read” – stuck with him. It reveled in satire, grotesquery and irreverence – the antithesis to rectitude, the Boy Scouts, school, Madison Avenue, and every other form of authority, especially one’s parents. “It was my entry portal into America,” he says.

Spiegelman believes that MAD was more subversive for his generation of protesters than either marijuana or LSD. It certainly radicalized him.

In the entry portal to CO-MIX, we learn that he idolized Harvey Kurtzman, a MAD founder who also drew the soft-porn satire “Little Annie Fannie” for Playboy. (Playboy would commission work from Spiegelman, too — more about that soon.) The obsessive Spiegelman, who didn’t lean toward political correctness, would work for any publication that published MAD artists, which meant that he drew for a Right Wing Cuban magazine that published Antonio Prohias, the exile who wrote the wordless Spy vs Spy strip that ran in the margins of MAD stories. Who said that practicing satire wasn’t about bringing its contradictions to life?

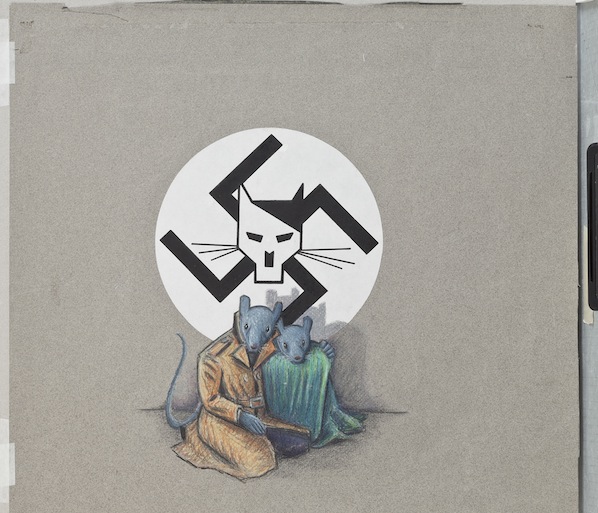

Original art for RAW no. 7: The Torn-Again Graphix Mag, 1985. Copyright © 1985 by Art Spiegelman. Used by permission of the artist and The Wylie Agency LLC.

In the first images in the smallish exhibition, the avowed ‘slob snob’ is already mocking his humble medium. Nothing was safe from his barbs then. He ridiculed the pulp mannerisms of comics crime stories. He found new ways to violate taboos in underground comics which specialized in clear-cutting everything respectable and smearing it with sex. He caught on with his peers by out-offending those who preceded him — like R. Crumb and S. Clay Wilson — in sheer grossness. Throwing spitballs, or worse, didn’t always work commercially. His grandly baroque lampoon “Pluto’s Retreat” mocked the notorious New York sex club via a Sergeant Pepper’s pantheon of wholesome comics characters as clients, all nude and game for sex in a lusty orgy. It was rejected by Playboy in 1972. (An underground comic printed it later. We should be grateful for that.) Anyone who saw this odd twist on the Last Judgment would think that Maus, attacked and stigmatized as transgressive, was a work of maturity, the softening of Art Spiegelman, which it was.

For evidence that Spiegelman’s experience with drawing animals goes back to his wild younger days, Shaggy Dog Story, a comic from Playboy in 1979 – now on the wall of the proper Jewish Museum – shows a glamorous woman, drawn in an erotic blend of art-deco and expressionist acute angles – coupling amorously with a dog. Then there’s the punch-line. The dog’s own canine girlfriend appears at the door. The “sin” here is that he cheated on her. There aren’t even any bitch jokes. Minus the bestiality and the porn details, it could be a shaggy dog story of betrayal from 1900.

Spiegelman would get back to dogs, a decade after Maus, in wholesome products that he (then a father) made for children. But in the galleries we see that in 1985 he devised a wildly contrarian line of trading cards and stickers (remember those?) produced by TOPPS Gum Inc., the company that produced baseball cards. He called them the Garbage Pail Kids, with names like GuilloTINA and Barfin’ Barbara. It was a salute to all the unpopular kids who were ignored or bullied, and an affront to the Cabbage Patch Dolls, a cloyingly cute corporate toy that couldn’t keep up with public demand. Spiegelman saw a softball to swing at.

Spiegelman would have been a driving force in comics if he had had stayed with satire, and built on the formal innovation — infused with influences from German expressionism and Picasso — that came in RAW (note the 3-letter title in homage to MAD). The magazine that he founded in the early 1980’s with his French wife Francoise Mouly introduced a new generation of innovative comic artists. Mouly led her husband from the vocabulary of comics into a broader language of 20th century experimentation. We can see from his adoption of color and cubism that Spiegelman was a willing omnivore, and that his fears of being a poor draftsman were exaggerated. Raw was where Maus was launched in the early 1980’s.

Maus was something altogether different. It played to type for the transgressive Spiegelman, a comic about the Shoah with animals as victims and aggressors. It was in bad taste, sniped detractors who either didn’t know the comics language or couldn’t trust it with anything serious. “The Holocaust was in bad taste,” Spiegelman retorted.

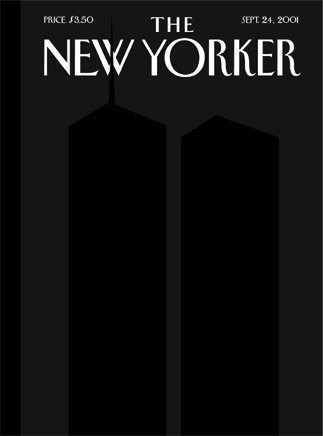

Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly, cover art for “Ground Zero,” The New Yorker, September 24, 2001, digital print. Copyright: Condé Nast.

Today, in strips on the gallery walls, Maus is still endlessly self-revealing, with the pain of inward exploration coming from and toward Spiegelman himself, rather than inflicted by him on yet another respectable target. Spiegelman emerged as the son who empathized with his father’s suffering, taking readers into a micro-history of the Holocaust, and situating himself uneasily in the continuum of a family that survived, as the story reminds us, by sheer luck.

It’ a story that, like the best of stories, you read and reread – poignant enough to keep you scrutinizing the little panels that stretch across the galleries at the Jewish Museum. Vestiges of MAD are still there, though there’s no satire in Maus’s staging of the improbable, yet punch lines creep into Spiegelman’s portrayal of his abrasive father, Vladek, who reminds you in broken English of the line that survivors are martyrs, but not saints.

The grossout Garbage Pail Kids gambit may also have fed into the tactile parts of Maus, where Vladek climbs over stinking corpses with typhus.

Back in the 1980’s, when Spiegelman published Maus, narrative art – art that told a story — was as derided as comics were. This has changed, due to Maus’s commercial success and to the growing popularity of the graphic novel, a term that still grates on Spiegelman, who prefers comics or comix.

If Spiegelman needed other achievements to point to, one of those could be his role in the erasure of the barriers between high and low art. The film critic J. Hoberman addresses that subject in an essay for the exhibition catalog, calling Spiegelman a rigorous scholar of his own medium – a high-minded champion of a form that’s been scorned as low-brow even by pop culture standards. With more than half of contemporary art galleries showing video and plenty of others showing a kind of satiric dada that Spiegelman left behind long ago, that high-low barrier isn’t worth worrying about any longer. For any artist who fears taking chances, wherever he or she might be on the high-low spectrum, Spiegelman offers an important lesson — courage is an essential under-represented element in most works of art.

After 9/11, when his children were at a schools in Manhattan after planes struck the World Trade Center, Spiegelman’s family was again the point of departure. Drawing himself as a mouse, Spiegelman wrote: “I remember my father trying to describe what the smoke in Auschwitz smelled like – the closest he got was telling me it was …’indescribable.’ That’s exactly what the air in lower Manhattan smelled like after September 11….Some parents were upset that their kids would miss some college prep classes.” Again, the final hook could have come from MAD.

Spiegelman took on the subject of the militarization of the United States and campaigns of racist attacks on Islam and anything that looked like it. His own confusion and his helplessness were at the core of that series of comics after 9/11, In the Shadow of No Towers, published in broadsheet newspapers in Europe and the US. The broadsheet format was a popularist anachronism in the service of how to think about what many were calling World War III. The panels often contained drawings that were upside down. The sky was falling, and Spiegelman depicted himself as part of the uncomprehending crowd, carrying a peace sign (another antiquation) that no one in the frames seemed to notice.

Gallows humor wasn’t all he had to offer. In covers for The New Yorker, a long journey from slob snobbery, Spiegelman drew freeze-frames of the zeitgeist, offering abrupt reality checks, as he still does, like his sketch in 1999 (not a cover) of a fearful concentration camp prisoner, holding his gold Oscar at the time that Life Is Beautiful with Roberto Benigni won that prize. The Hollywood Holocaust – the bad taste debate again.

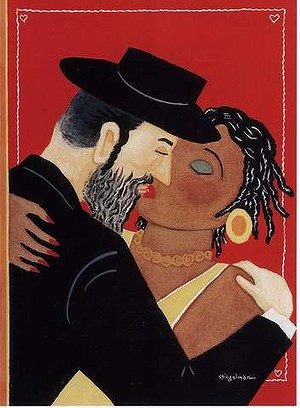

Cover art for “Valentine’s Day,” The New Yorker, February 15, 1993. Copyright © 1993 by Art Spiegelman. Used by permission of the artist and The Wylie Agency LLC.

Also on view at the Jewish Museum is the New Yorker cover of a Hasidic man kissing a black woman with dreadlocks, for Valentine’s Day in 1993. Spiegelman forced the well-meaning public (and the enraged folks who republished the image in order to berate the artist publicly) to decide which was the worse taboo – the interracial violence in the Brooklyn streets which had preceded his drawing, or the specter of interracial sex that the cover seemed to condone or promote.

Missing from the exhibition’s selection of New Yorker work is Spiegelman’s cover drawing of a policeman shooting human silhouettes at a carnival. “41 Shots, 10 Cents” was published after officers from the Street Crimes Unit of the NYPD shot the unarmed African street vendor Amadou Diallo 41 times as he was entering his home in the Bronx in February 1999. Once again, Spiegelman was accused of bad taste. Some might have said the same thing when the officers who shot Diallo were acquitted.

There’s an homage to Maus in that image of cops at target practice: mute stuffed animal prizes sit on the shelves of the carnival booth as a policeman in blue takes aim at the black figures.

Those New Yorker covers come close to filling the space that a painting might occupy on a museum wall. Putting comics on the walls of a gallery challenges the museum visitor. It can leave you leaning and squinting and struggling to stay with a story over dozens of panels. There’s an argument that objects should be shown in the form and at the scale that they were made. Where else but in a museum will the public see those objects themselves? And isn’t it the place of the art museum to assess those objects as objects, i.e., as works of art themselves?

It’s fascinating to see those drawings and the sketches that led to them, just as it is to see Spiegelman’s improbable but logical path toward Maus, an extraordinary work of art. Yet the exhibition, at its core, shows us how Spiegelman arrived at what became Maus, and how the volume was made.

Maus reached its audience as a book. That book and others by Spiegelman brought the public to the museum exhibition. Now the exhibition is sure to get the public back to the books, if only to take in everything that’s on the page. Books saved, or kept alive by the lowly comic. The slob snob wins again.

David D’Arcy, who lives in New York, is a programmer for the Haifa International Film Festival in Israel. He reviews films for Screen International. His film blog, Outtakes, is at artinfo.com. He writes about art for many publications, including The Art Newspaper. He produced and co-wrote the documentary, Portrait of Wally (2012), about the fight over a Nazi-looted painting found at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan.